There was a young schoolboy in the audience that day, who was thrilled and inspired by the story of a secret code which no one could break. His name was Michael Ventris and sixteen years later, on 1 July 1952, he made a BBC radio broadcast which was to secure his place in archaeological and history books for ever. He announced that he’d deciphered Linear B, Europe’s earliest known, and previously incomprehensible, writing system.

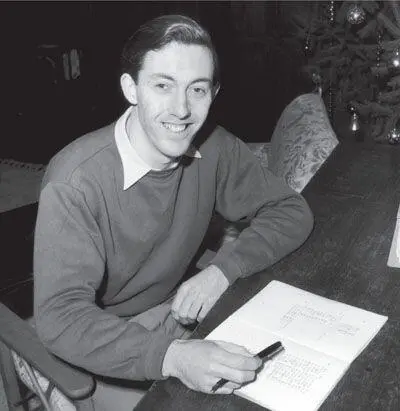

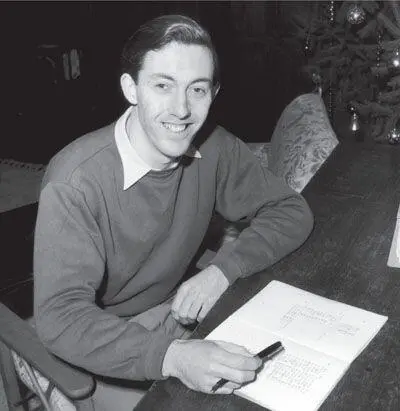

Michael wasn’t an archaeologist or scholar, he was an architect, but he was fluent in several languages, and his life’s passion was cracking the Linear B code. He was a loner, an outsider, an unconventional thinker from an unconventional background who’d been brought up by his divorced Polish mother and educated for a time in Switzerland.

Throughout his years of architectural training and practice, which was interrupted by the war, in which he served as an RAF navigator, Ventris worried away at Linear B. He worked on the problem through a series of small, detailed steps, helped by the researches and insights of others, like the American classical scholar and archaeologist Alice Kober, who observed that certain words in Linear B inscriptions had changing word endings — perhaps declensions like Latin or Greek.

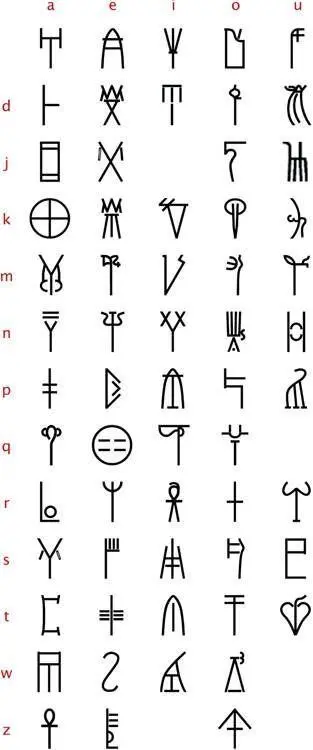

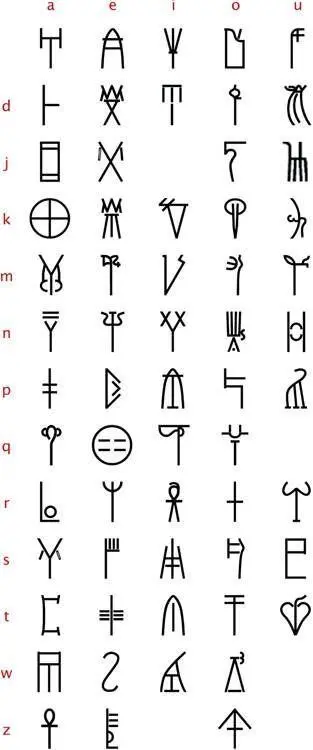

Ventris took this clue and painstakingly constructed a series of grids mapping out the symbols on the tablets and associating them with consonants and vowels. He still didn’t know which consonants and vowels they were, but he had learned enough about the structure of the underlying language to begin guessing.

Linear B tablets had also been discovered on the Greek mainland, and Ventris believed that some of the chains of symbols on the Cretan tablets were names. But certain names appeared only in the Cretan texts, so Ventris made the inspired guess that those names applied to cities on the island. This proved to be correct. This gave him a set of symbols he could decipher from. He soon unlocked much of the text and demonstrated beyond any doubt that Linear B was the writing system used by the Mycenaean inhabitants of continental Greece, and that the underlying language was an archaic dialect of Greek, centuries older than anything previously known.

Instant celebrity followed, and in 1955 Ventris published, with the philologist John Chadwick, the monograph Documents in Mycenaean Greek. The following year, at the age of thirty-four, he was dead, killed in a car crash. John Chadwick said of the particular genius of Michael Ventris: ‘Ventris was able to see, in the confusing diversity of these signs, an overall pattern and to pinpoint certain constants which revealed the underlying structure. It was this quality — the gift of being able to make order out of apparent confusion — that is the sign of greatness amongst the scholars in this field.’

Linear B is based on combinations of sounds

Michael Ventris cracked the Linear B code

By 1200 BC, different writing forms were being used in India, China, Europe and Egypt by 1200 BC. One feature that cuneiform, hieroglyphs and Chinese characters shared was that all three could be used to transcribe either words or syllables. Both the Chinese writing system, which developed around 2000 BC, and the Egyptian hieroglyphs — which means ‘writing of the gods’ — are exceedingly beautiful, functional as well as artistic. They’re complex, too, because they’re made up of several different kinds of signs.

Hieroglyphs comprised pictograms, phonograms and determinatives — signs used to indicate which category a sign is in. In Chinese a single sound can represent several things, depending on how it’s written. For example, the sound shi can mean ‘to know’, ‘power’, ‘world’, ‘to love’, and many other things, according to the other elements with which it’s combined. Each character is formed of a key, which gives the basic meaning, and a phonetic element to indicate pronunciation. It doesn’t stop there, though. The calligraphy of Chinese — the forming of the characters — also contributes to meaning, through the style of the writing, the colour of the ink and the intensity of the stroke. So, to varying degrees, the systems of cuneiform, hieroglyphs and Chinese meant that you had to master a large number of signs and characters to read and write them.

Then, a thousand years before the birth of Christ, a massive change took place in the history of writing: the alphabet was invented. Not overnight, obviously, but gradually in different places, over a long period of development, crossover and osmosis.

An alphabet works differently from the older systems. The key difference was the inspiration that, once you have a set of symbols that represent sounds and not things, you can represent any noise, any word in any language, using the same symbols. In principle, it’s possible to write almost anything with about thirty letters. More or less. We’ve got twenty-six letters, but that’s not enough for us to transcribe all the sounds in English, which is why our spelling is more difficult to learn than, say, Italian.

English has what’s called a deep orthography — there’s no one-to-one correspondence between the sounds (phonemes) and the letters (graphemes) that represent them. It’s notorious for its inconsistencies, for instance in words where the same letters are pronounced differently like cough, bough, dough and tough ; or chat, chute and scholar . On the other hand, sometimes different letters are pronounced the same way, like the sh sound in ship, initial and machine . So learning to spell and write English can be difficult, but twenty-six letters is nothing like the 1,000 basic signs needed for writing Chinese, the hundreds of hieroglyphs used in Egyptian, or the 600 cuneiform signs that were hammered for six years into students in the scribe schools in Mesopotamia. With an alphabet came the possibility of spreading learning out from the elite few to the many.

So where did our alphabet come from? It’s a story of twists and turns and many scenes. Like so much of our culture, our letters are an overseas import, brought to these shores by the Romans. But it’s not as simple as that. The Romans didn’t invent the alphabet either — they had adopted the Etruscans’ writing system, which they in turn had borrowed and adapted from the Greeks. We get our word alphabet from their two first letters — alpha and beta . But where did the Greeks get their alphabet from? Some romantically minded scholars have proposed that a brilliant contemporary of Homer was inspired to invent the alphabet to record the poet’s oral epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey . It seems unlikely, but Homer does give us a clue about the origins of writing. In the Iliad and the Odyssey , he mentions the Phoenicians, traders who travelled the Mediterranean on ships.

Another Greek myth also points to the Phoenicians. Herodotus claimed that the alphabet was brought to Greece by Cadmus, the legendary founder of the Phoenician city of Thebes. The Phoenicians came from the coastal areas of present-day Israel and Lebanon and part of Egypt. Their cities were places like Tyre, Sidon and Beirut.

‘Phoenician’ means ‘dealer in purple’; one of their most important items of merchandise was the purple dye extracted from a large type of sea snail. We call them Phoenicians, but they called themselves Kenaani or Canaanites — as in the Canaan of the Bible, the land flowing with milk and honey.

Читать дальше