The French academic (and coiner of the word franglais ) René Etiemble was full of admiration for the decipherers who wrestled with the messages from the past: ‘Let us ask ourselves, positively, flatly, whether perhaps we should not admire those who deciphered hieroglyphs, cuneiform or Cretan Linear B, a little more … than those who designed the first pictograms, or who created a system for representing a complete vocabulary with a few alphabetic signs.’ These were men who made it their life’s mission to interpret the obscure signs that were engraved on stone, painted on walls and tombs or scratched in clay. They were puzzle-solvers, detectives, archaeologists and linguists rolled into one. While Jean-François Champollion was working on his first translation of the Rosetta Stone hieroglyphs in 1822, another group of scholars was making momentous discoveries about cuneiform.

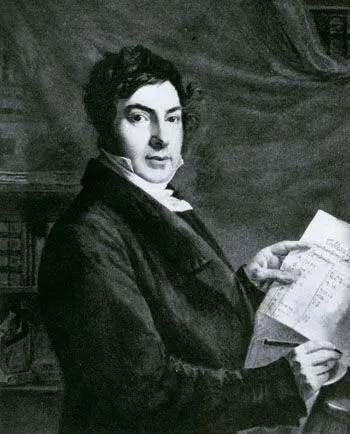

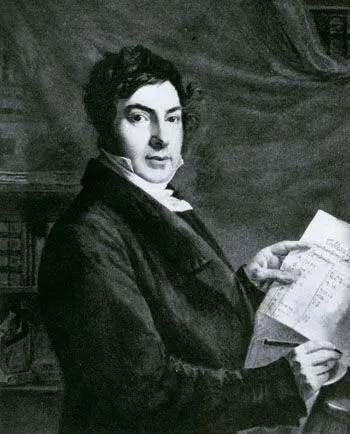

Georg Friedrich Grotefend, one of the greatest decipherers

It was a piece of inspired guesswork by a scholar and schoolteacher from Germany that led the way. Georg Friedrich Grotefend was an accomplished Latinist and linguist, but he had no background in Oriental languages, so it’s all the more extraordinary that in 1802 he succeeded in partially deciphering the old Persian cuneiform writing and provided the foundation for later work to provide a complete translation of the signs.

Archaeologists had already started collecting artefacts from ancient Assyria and Babylonia and had noted the strange script on seals and clay cylinders, and on the walls of the ruined palaces of the Persian kings at Persepolis. Various travellers and scholars, as far back as the seventeenth century, had copied and written about these mysterious scripts, so people knew about them — they just couldn’t understand them. Then the Danish government sent the German mathematician and cartographer Carsten Niebuhr on a scientific exploration of Egypt, Syria and Arabia. On his way back, Carsten made detailed and laborious copies of the inscriptions at Persepolis — sacrificing his sight in the process — and in the early 1780s published three volumes of his work. At last, scholars in Europe had extensive and accurate records to use, and the work began in earnest.

By the time Grotefend came along scholars had recognized there were three different forms of the script at Persopolis and that the systems were alphabetic. It’s a bit like a scholarly detective story, this quest to decipher and understand. It was all about finding clues and trying to fill gaps, comparing notes and building on other people’s theories until the moment when things clicked into place. Grotefend looked at the three different scripts and decided that they represented three different languages. Here was a powerful king communicating his edict or story in more than one language so that it could be understood across an empire. He also logically worked out that the first script must be in old Persian, the language of the kings, and the other two must be translations. He was feeling his way through deduction, common sense, available information and his linguistic training.

It was like trying to solve the most nightmarishly difficult Times crossword you can imagine. He picked out repetitive phrases, which were used to honour Persian kings. He then compared those letters with the kings’ names, which he knew from Greek historical texts, followed the pattern of inscriptions in Middle Persian which linguists had recently deciphered and eventually worked out the approximate phonic values of about ten characters.

The sting in the tail to Grotefend’s story is that the academic world turned up its nose when his paper was presented to the Göttingen Academy of Sciences. They didn’t understand the inductive method he’d used and, frankly, they didn’t believe a schoolteacher who specialized in Latin and Italian and hadn’t studied Oriental languages. It would be another thirteen years before a friend eventually published the paper.

Other scholars then built on Grotefend’s work and in 1905 François Thureau-Dangin produced the first translation of Sumerian, man’s earliest identified writing and the original version of cuneiform — which was where we started this chapter.

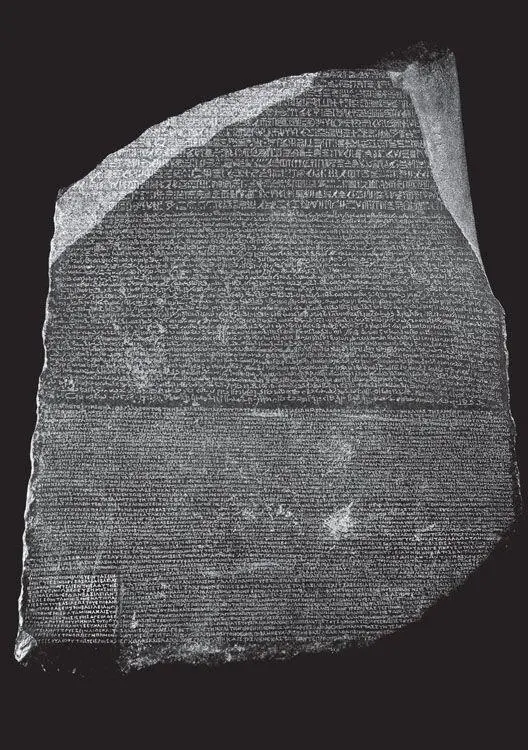

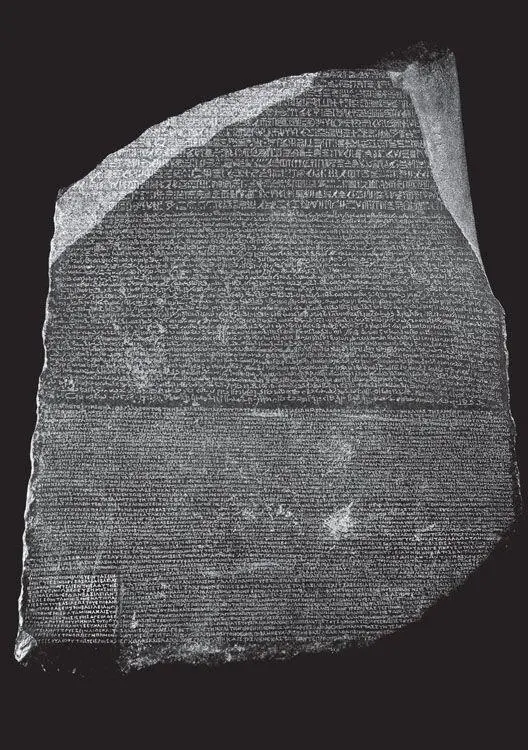

The Rosetta Stone

We don’t know whether writing was discovered or invented independently in different parts of the world, or whether it spread by osmosis. But by 1200 BC writing was being used in India, China, Europe and, of course, Egypt. Some scripts, like Cretan Linear A, are still a mystery, but we did find the key to the words of the pharaohs, these beautiful, exotic hieroglyphics which cover countless monuments and tombs, thanks to the Rosetta Stone.

The Rosetta Stone is a big lump of dark granite 45 inches by 28 inches by 22 inches, on which there are three inscriptions. The upper text is in hieroglyphs, the middle portion is demotic script (the language which came between Late Egyptian and Coptic), and the lowest is in classical Greek. Because it presents essentially the same text in all three scripts, scholars could compare the Greek words, which they knew, with the hieroglyphs and their knowledge of later Coptic, and so learn to read the signs.

The stone was discovered during Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt in 1799 and seized by the British when they defeated the French in Alexandria in 1801. It dates from the second century, when the priests who had gathered at Memphis to celebrate the arrival of the young Ptolemy V composed a decree in his honour which was copied on to stone, with the two translations. The stone was placed in the British Museum in 1802 and it’s been there ever since.

Jean-François Champollion deciphered the first hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone, divided into hieroglyphs, demotic script and classical Greek

It was a brilliant young French scholar and philologist called Jean-François Champollion who first deciphered the hieroglyphs on the stone and demonstrated that the Egyptian writing system was a combination of phonetic and ideographic signs. Like so many of the other code-breakers of the ancient writings, he was a superb linguist with a genius for inspired thinking and deduction. He was also obsessed, a workaholic who devoted his life to his studies and died at the age of forty-two. He first heard of the Rosetta Stone as a boy, and it fired an interest in hieroglyphics which burned fiercely throughout his student days in Grenoble. There he studied a multitude of languages, including Latin, Greek, Sanskrit and Coptic, and became convinced that Coptic was simply a late form of the language which the ancient Egyptians had spoken.

Champollion spent three years working on deciphering the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone, and his monumental contribution to history was to prove that hieroglyphs were not simply pictures, but that they represented sounds as well. His 1824 work Précis du système hiéroglyphique gave birth to the modern field of Egyptology.

In 1936 the famous archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who had excavated the ancient palace of Knossos in Crete, held a conference in London on the mysterious writing system inscribed on the clay tablets which he had uncovered, a script he had spent decades trying to decipher, without success.

Читать дальше