Orientation: A variety of bisexual arrangements characterize these duck species. Some female Lesser Scaups (perhaps 30–40 percent of the population) have a seasonal alternation between same-sex and opposite-sex pairings: they begin the breeding season in heterosexual pairs, but end it in same-sex associations. Most Australian Shelduck females in homosexual pairs probably go on to form heterosexual bonds as adults. Musk Duck males display to both females and other males; some of the males they attract are also interested in females, but others are apparently only attracted to the courting male.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

As described above, separation of heterosexual pairs with subsequent female single-parenting (or coparenting) is the usual pattern for Lesser Scaup families. Several other alternative parenting and pairing arrangements occur in these species. Occasionally a female Lesser Scaup associates with a mated pair and even lays eggs in their nest. Musk Ducks often lay their eggs in other birds’ nests, where they are foster-parented by both their own and foreign species—including many other kinds of ducks (e.g., the blue-billed duck, Oxyura australis ) as well as Dusky Moorhens. For their part, Lesser Scaups occasionally raise ducklings of other species of ducks, hatched from eggs that have been laid in their nests by, for example, redheads ( Aythya americana ). Australian Shelducks sometimes foster-parent chicks as well: about 5 percent of all broods contain “extra” ducklings from other families, and about 1 percent of all ducklings are adopted or “exchanged” between families. Lesser Scaup ducklings are occasionally abandoned by their mothers and may be adopted into other families. Abandonment of eggs is also prevalent: female Lesser Scaups may desert entire clutches, while egg DUMPING is common in Australian Shelducks. Many Shelduck pairs copulate but then lay or abandon the resulting eggs in caves, along the shore, or on islands, never incubating or hatching them. Most of these pairs—who may constitute close to half the population—have been unable to secure a breeding territory of their own. Many other birds are non-breeders as well: a large proportion of Lesser Scaups of both sexes, and Australian Shelduck females, are younger birds that are sexually mature but unpaired. In addition, it is thought that reproduction in younger male Musk Ducks may be suppressed by the presence of older males.

Although many Australian Shelducks form long-lasting heterosexual bonds, about 10 percent of breeding pairs divorce, and many more juvenile pairs separate. In Lesser Scaups, nonmonogamous copulations are common, accounting for more than half of all heterosexual activity. Many of these are rapes or forced copulations performed by paired males on females other than their mate; occasionally groups of up to eight males will pursue a female and try to mate with her. Only about 20 percent of such rapes involve penetration—the male Lesser Scaup, like most waterfowl (but unlike most other birds), does have a penis. More than a quarter of all such attempts are nonreproductive, occurring too early in the breeding season, during incubation, after breeding, or on nonbreeding females. In fact, the highest rates of attempted rape occur on females just before their molting period, when they are nonfertilizable. In Australian Shelducks, it is the females who vigorously pursue males, often courting already paired drakes in dramatic aerial chases. One or several females may try to maneuver in between a mated pair to separate the male, even grabbing at the tail feathers of his mate to force her to change direction. Females frequently suffer broken wings and may even be killed when they hit obstacles during such high-speed chases.

Other Species

Interspecies homosexual pairs involving several other kinds of ducks and geese have been observed in captive birds. A pair consisting of a female Common Shelduck ( Tadorna tadorna ) with a female Egyptian Goose ( Alopochen aegyptiacus ), for example, both laid eggs in a shared nest and jointly incubated them.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

*Afton, A. D. (1993) “Post-Hatch Brood Amalgamation in Lesser Scaup: Female Behavior and Return Rates, and Duckling Survival.” Prairie Naturalist 25:227-35.

———(1985) “Forced Copulation as a Reproductive Strategy of Male Lesser Scaup: A Field Test of Some Predictions.” Behavior 92:146–67.

———(1984) “Influence of Age and Time on Reproductive Performance of Female Lesser Scaup.” Auk 101:255–65.

Attiwell, A. R., J. M. Bourne, and S. A. Parker (1981) “Possible Nest-Parasitism in the Australian Stiff-Tailed Ducks (Anatidae: Oxyurini).” Emu 81:41–42.

Bellrose, F. C. (1976) Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America . Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole.

Fullagar, P. J., and M. Carbonell (1986) “The Display Postures of the Male Musk Duck.” Wildfowl 37:142–50.

Gehrman, K. H. (1951) “An Ecological Study of the Lesser Scaup Duck ( Aythya affinis Eyton) at West Medical Lake, Spokane County, Washington.” Master’s thesis, State College of Washington (Washington State University).

*Hochbaum, H. A. (1944) The Canvasback on a Prairie Marsh. Washington, D.C.: American Wildlife Institute.

*Johnsgard, P. A. (1966) “Behavior of the Australian Musk Duck and Blue-billed Duck.” Auk 83:98–110.

*Low, G. C., and Marquess of Tavistock (1935) “The Extent to Which Captivity Modifies the Habits of Birds.” Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 55:144–54.

*Lowe, V. T. (1966) “Notes on the Musk Duck Biziura lobata.” Emu 65:279–89.

*Munro, J. A. (1941) “Studies of Waterfowl in British Columbia: Greater Scaup Duck, Lesser Scaup Duck.” Canadian Journal of Research, section D 19:113–38.

O’Brien, R. M. (1990) “Musk Duck, Biziura lobata.” In S. Marchant and P. J. Higgins, eds., Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds, vol. 1, pp. 1152–60. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Oring, L. W. (1964) “Behavior and Ecology of Certain Ducks During the Postbreeding Period.” Journal of Wildlife Management 28:223–33.

*Riggert, T. L. (1977) “The Biology of the Mountain Duck on Rottnest Island, Western Australia.” Wildlife Monographs 52:1–67.

Rogers, D. I. (1990) “Australian Shelduck, Tadorna tadornoides.” In S. Marchant and P. J. Higgins, eds., Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds, vol. 1, pp. 1210-18. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

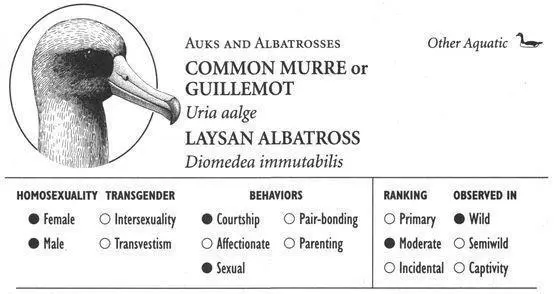

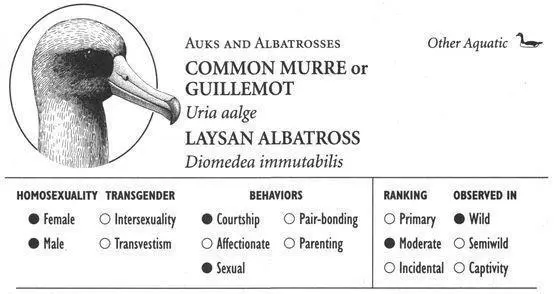

COMMON MURRE

IDENTIFICATION: A gull-sized, web-footed bird with contrasting black upperparts and white underparts; some individuals have a white eye ring. DISTRIBUTION: Northern oceans and adjacent coasts. HABITAT: Marine coasts, bays, islands. STUDY AREAS: Gannet Islands, Labrador, Canada; Skomer Island, Wales; subspecies U.a. aalge and U.a. albionis.

LAYSAN ALBATROSS

IDENTIFICATION: A large, white-plumaged, gull-like bird with an enorous wingspan (over 6½ feet), a dark back, and a grayish black wash on the face. DISTRIBUTION: Northern Pacific Ocean. HABITAT: Oceangoing; breeds on oceanic islands. STUDY AREA: Eastern Island in the Midway Atoll.

Читать дальше