In addition to such polygamous associations, several other alternative family arrangements occur. “Foster parenting” or adoption takes place frequently among Black Swans (and occasionally in Mute Swans). In some colonies, more than two-thirds of all cygnets are raised in broods that combine offspring from 2–4 families (and occasionally from as many as 30 different families). Such BROOD AMALGAMATIONS—which may have up to 40 youngsters—are attended by a single pair of adults, who are not necessarily the biological parents of any of the cygnets. Adoption also occasionally occurs when adults “steal” eggs laid near their nest by other birds, rolling them into their own nest. Single parenting is a prominent feature of Black Swan social life: often a male or female deserts its mate during incubation, and in some colonies the majority of nests are attended by single parents. Occasionally, a pair “separates” rather than divorces, with one bird taking the newly hatched young while the other remains to incubate the rest of the eggs. Among Mute Swans, the divorce rate is 3–10 percent of all pairs, and about a fifth of all birds have two to four mates during their lifetime. Some Mute Swans are nonmonogamous, courting or mating with another bird while remaining paired with their partner; some of this activity may involve REVERSE copulations (in which the female mounts the male). Many within-pair copulations are nonprocreative, since most pairs mate far more often than is required for fertilization of the eggs. Swans also sometimes engage in behaviors that are counterreproductive. A third of all Black Swan eggs, for example, are lost through abandonment of the nest by the parent (s), while 3 percent of Mute Swan parents desert their nests, and birds often attack and even kill youngsters that stray into their territory. Eggs are sometimes also destroyed during territorial disputes, and adult birds may be killed as a direct result of such attacks as well (accounting for 3 percent of all deaths).

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

Bacon, P. J., and P. Andersen-Harild (1989) “Mute Swan.” In 1. Newton, ed., Lifetime Reproduction in Birds, pp. 363–86. London: Academic Press.

Braithwaite, L. W. (1982) “Ecological Studies of the Black Swan. IV. The Timing and Success of Breeding on Two Nearby Lakes on the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales.” Australian Wildlife Research 9:261–75.

*———(1981) “Ecological Studies of the Black Swan. III. Behavior and Social Organization.” Australian Wildlife Research 8:135–46.

*———(1970) “The Black Swan.” Australian Natural History 16:375-79.

Brugger, C., and M. Taborsky (1994) “Male Incubation and Its Effect on Reproductive Success in the Black Swan, Cygnus atratus.” Ethology 96:138–46.

Ciaranca, M. A., C. C. Allin, and G. S. Jones (1997) “Mute Swan ( Cygnus olor).” In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds., The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century, no. 273. Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists’ Union.

Dewer, J. M. (1942) “Ménage à Trois in the Mute Swan.” British Birds 30:178.

Huxley, J. S. (1947) “Display of the Mute Swan.” British Birds 40:130–34.

*Kear, J. (1972) “Reproduction and Family Life.” In P. Scott, ed., The Swans, pp. 79–124. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

*Low, G. C. and Marquess of Tavistock (1935) “The Extent to Which Captivity Modifies the Habits of Birds.” Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 55:144–54.

Mathiasson, S. (1987) “Parents, Children, and Grandchildren—Maturity Process, Reproduction Strategy, and Migratory Behavior of Three Generations and Two Year-Classes of Mute Swans Cygnus olor.” In M. O. G. Eriksson, ed., Proceedings of the Fifth Nordic Ornithological Congress, 1985, pp. 60–70. Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum et Litterarum Gothoburgensis Zoologica no. 14. Göteborg: Kungl. Vetenskaps- och Vitterhets-Samhället.

Minton, C. D. T. (1968) “Pairing and Breeding of Mute Swans.” Wildfowl 19:41–60.

*O’Brien, R. M. (1990) “Black Swan, Cygnus atratus.” In S. Marchant and P. J. Higgins, eds., Handbook of Australian, New Zealand, and Antarctic Birds, vol. 1, pp.1178–89. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Ogilvie, M. A. (1972) “Distribution, Numbers, and Migration.” In P. Scott, ed., The Swans, pp. 29–55. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Rees, E. C., P. Lievesley, R. A. Pettifor, and C. Perrins (1996) “Mate Fidelity in Swans: An Interspecific Comparison.” In J. M. Black, ed., Partnerships in Birds: The Study of Monogamy , pp. 118–37. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

*Ritchie, J. P. (1926) “Nesting of Two Male Swans.” Scottish Naturalist 159:95.

*Schönfeld, M. (1985) “Beitrag zur Biologie der Schwane: ‘Männchenpaar’ zwischen Graugans und Hock-erschwan [Contribution to the Biology of Swans: ‘Male Pairing’ Between a Greylag Goose and a Mute Swan].” Der Falke 32:208.

Sears, J. (1992) “Extra-Pair Copulation by Breeding Male Mute Swan.” British Birds 85:558–59.

*Whitaker, J. (1885) “Swans’ Nests.” The Zoologist 9:263–64.

Williams, M. (1981) “The Demography of New Zealand’s Cygnus atratus Population.” In G. V. T. Matthews and M. Smart, eds., Proceedings of the 2nd International Swan Symposium (Sapporo, Japan), pp. 147–61. Slimbridge: International Waterfowl Research Bureau.

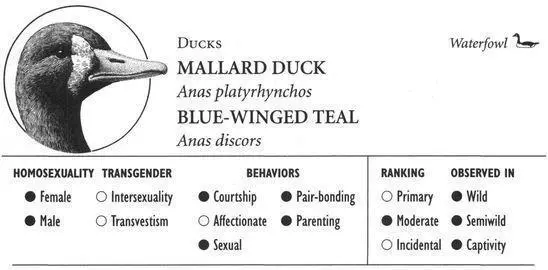

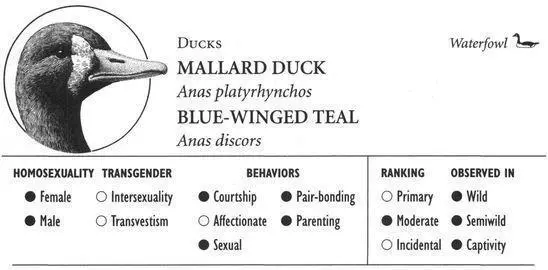

MALLARD DUCK

IDENTIFICATION: A familiar duck with a blue wing patch, an iridescent green head and white collar in males, and brown, mottled plumage in females. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout the Northern Hemisphere; Australia and New Zealand. HABITAT: Wetlands. STUDY AREAS: J. Rulon Miller Wildlife Refuge, McDonogh, New Jersey; Haren and Middleburg, the Netherlands; Augsburg, Germany, and the Max-Planck Institute, Seewiesen, Germany; Delta Waterfowl Research Station, Lake Manitoba, Canada; subspecies A.p. platyrhynchos, the Common Mallard.

BLUE-WINGED TEAL

IDENTIFICATION: A grayish brown duck with a light blue upper-wing patch, tawny spotted underparts, and white, crescent-shaped facial stripes in males. DISTRIBUTION: Northern and central North America; winters in Central America and northern South America. HABITAT: Marshes, lakes, streams. STUDY AREA: Delta Waterfowl Research Station, Lake Manitoba, Canada.

Social Organization

Mallard Ducks and Blue-winged Teals are highly sociable birds, usually congregating in their own flocks of hundreds or (in Mallards) even thousands for most of the year. During the breeding season, they typically form monogamous pairs, although many variations exist. As in many other duck species, heterosexual pairs usually separate soon after incubation begins. Females then incubate the eggs and raise their families on their own.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Mallards sometimes mount and copulate with other females in the early fall, when ducks congregate in groups and begin to establish pair-bonds. Two females may engage in the PUMPING display, a prelude or invitation to mating in which the head is bobbed up and down so that the bill touches the water in a horizontal position. Following this, one female flattens her body on the water and extends her neck, allowing the other female to mount. While copulating, the mounting female may grab her partner’s neck feathers in her bill or gently peck at her head. After dismounting, she performs a concluding display (also shown by females in heterosexual interactions) in which she dips her head in the water and then shakes the drops down her back while beating her wings. Homosexual mountings occasionally occur later in the season between heterosexually paired females and single females.

Читать дальше