*Lebret, T. (1961) “The Pair Formation in the Annual Cycle of the Mallard, Anas platyrhynchos L.” Ardea 49:97–157.

*Lorenz, K. (1991) Here Am I—Where Are You? The Behavior of the Greylag Goose . New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

*———(1935) “Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vögels.” Journal für Ornithologie 83:10–213, 289–413. Reprinted as “Companions as Factors in the Bird’s Environment.” In K. Lorenz (1970), Studies in Animal and Human Behavior, vol. 1, pp. 101-258. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Losito, M. P., and G. A. Baldassarre (1996) “Pair-bond Dissolution in Mallards.” Auk 113:692-95.

McKinney, F., S. R. Derrickson, and P. Minneau (1983) “Forced Copulation in Waterfowl.” Behavior 86:250–94.

Mjelstad, H., and M. Sætersdal (1990) “Reforming of Resident Mallard Pairs Anas platyrhynchos, Rule Rather Than Exception?” Wildfowl 41:150–51.

Raitasuo, K. (1964) “Social Behavior of the Mallard, Anas platyrhynchos, in the Course of the Annual Cycle.” Papers on Game Research (Helsinki) 24:1-72.

*Ramsay, A. O. (1956) “Seasonal Patterns in the Epigamic Displays of Some Surface-Feeding Ducks.” Wilson Bulletin 68:275–81.

*Schutz, F. (1965) “Homosexualität und Pragung: Eine experimentelle Untersuchung an Enten [Homosexuality and Developmental Imprinting: An Experimental Investigation of Ducks].” Psychologische Forschung 28:439–63.

*Titman, R. D., and J. K. Lowther (1975) “The Breeding Behavior of a Crowded Population of Mallards.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 53:1270–83.

Weston, M. (1988) “Unusual Behavior in Mallards.” Vogeljaar 36:259.

Williams, D. M. (1983) “Mate Choice in the Mallard.” In P. Bateson, ed., Mate Choice, pp. 33–50. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

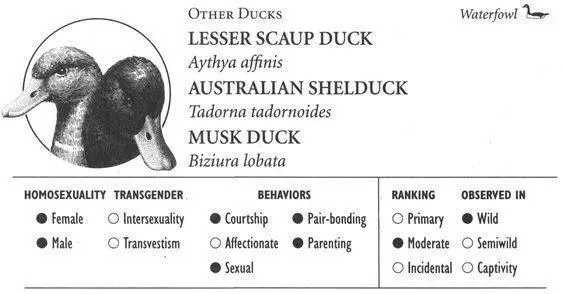

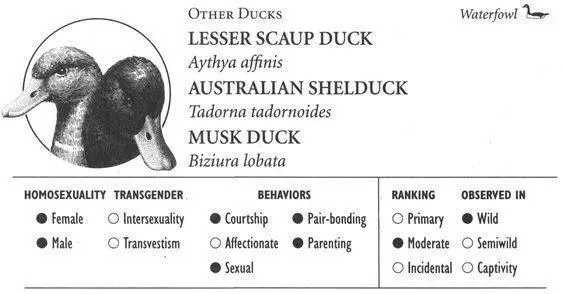

LESSER SCAUP DUCK

IDENTIFICATION: A broad-billed duck with a purplish black head and breast and white underparts in males, and a dark head and brownish plumage in females. DISTRIBUTION: Northern and central North America; winters in southern United States and Mexico. HABITAT: Lakes, marshes, lagoons. STUDY AREAS: Lake Manitoba (Delta Marsh) and near Erickson, Manitoba; Cariboo region of British Columbia, Canada, including Watson and 150 Mile Lakes.

AUSTRALIAN SHELDUCK

IDENTIFICATION: Cinnamon breast, dark green head and back, and white collar; adult females have white eye and bill rings. DISTRIBUTION: Southern Australia, Tasmania. HABITAT: Marshes, lakes, lagoons. STUDY AREA: Rottnest Island, Western Australia.

MUSK DUCK

IDENTIFICATION: A large, grayish duck with a prominent lobe hanging from the lower bill, and a spike-fan tail. DISTRIBUTION: Southern Australia, Tasmania. HABITAT: Swamps, lakes, other wetlands. STUDY AREA: Kangaroo Lake, Victoria, Australia.

Social Organization

Lesser Scaup Ducks are highly social, gathering into large waterborne flocks or “rafts” that may number in the tens of thousands. They form pair-bonds during the mating season, but males typically leave their mates following egg-laying (see below) and join large all-male groups. Australian Shelducks also form mated pairs during the breeding season (both parents care for the young) but otherwise associate in flocks. Musk Ducks are largely solitary except during the mating season; adult males are territorial, and they are probably polygamous or promiscuous (copulating with more than one female).

Description

Behavioral Expression: Male Lesser Scaup Ducks occasionally try to copulate with one another; drakes who participate in such homosexual activity are usually unpaired birds. While same-sex mounting does not occur among females, coparenting does. In this species, males usually abandon their female mates shortly after incubation of the eggs begins. Most females take care of their young entirely on their own as single parents, but sometimes two females join together and help each other raise their families. Accompanying their combined broods of 20 or more ducklings, the two females cooperate in all parental duties, including coordinated defense of the youngsters. If a predator or intruder approaches, one female distracts it by boldly approaching and feigning an injury, while her partner stealthily leads all of the ducklings away to safety. As their offspring get older, however, female coparents show less of this “distraction” behavior; at the approach of a predator, they may depart with one another and temporarily leave their ducklings behind to fend for themselves. Occasionally three females join forces and raise their combined broods—as many as 50 or more ducklings—as a parenting trio. Interestingly, duckling survival rates are not significantly different in families with one as opposed to two (or three) female parents.

Female Australian Shelducks often court one another and form homosexual pair-bonds. In December, when birds begin pairing, females display to each other with ritual preening movements and chases. These often develop into a full-fledged WATER-THRASHING DISPLAY, in which one female swims toward the other while making sideways pointing movements with her outstretched head and neck. She may also dive and resurface, then chase after the other female. Her partner is frequently captivated by this performance and responds by enthusiastically diving and chasing in return; the two females may, as a result, form a bond that lasts until the next pairing season. Females that engage in homosexual courtship and pairing are usually younger adult or juvenile birds.

Male Musk Ducks perform an extraordinary courtship display that attracts both males and females. The male arches his back and lifts his head up, engorging his large throat pouch; at the same time he fans and bends his tail forward over his back at an extreme angle—a feat made possible because of two extra vertebrae. This gives the bird an astounding, reptilian appearance. While in this posture, he kicks both feet backward or to the side, producing enormously loud splashes or jets of water. Multiple kicks of various types are given in series, and often the courting male rapidly back-paddles in between kicks. He also produces a wide variety of sounds during these PADDLE-KICK, PLONK-KICK, and WHISTLE-KICK displays, including ker-plonks (made by the kicking and splashing) combined with whirr or cuc-cuc vocalizations, and even a distinctive whistling sound. In addition, many displaying males emit a musky odor (hence the name of the bird), and their plumage is so oily that puddles of oil may form on the surface of the water around them. This display—perhaps one of the most dramatic of all birds—draws both males and females, who crowd around the courting male. Often, males appear to be more attracted than females, swimming much closer to the displaying male and sometimes even making physical contact by gently and repeatedly nudging their breast against his shoulder. The displaying male is in a trancelike state and rarely responds directly to any of the onlookers. Indeed, although homosexual copulation has not been observed as a part of these displays, heterosexual mating has hardly ever been seen during such courtship sessions either.

A male Musk Duck ( left ) attracted to another male performing a “whistle-kick” as part of an elaborate courtship display sequence

Frequency: Homosexual mounting probably occurs only occasionally in Lesser Scaup Ducks, but female coparenting is a regular feature of some populations. As many as a quarter to a third or more of all families have two mothers, although in other populations they are less frequent, comprising about 12 percent of families in some years. Same-sex courtship and pairing occur frequently among younger Australian Shelduck females, while male Musk Ducks are routinely attracted to displaying males.

Читать дальше