A variety of alternative parenting arrangements are also found in these species. About 8 percent of all Common Murre chicks have “baby-sitters”—a pair of birds other than their parents who help brood (keep warm), protect, and sometimes feed the chick (even when the youngster’s parents are not away). Most such helpers are nonbreeders; others have tried but failed to breed, while some have finished raising their family or are also taking care of their own chick. In addition, pair separation and single parenting is routine in Common Murres: when a chick is old enough to leave the colony, only its father accompanies it to sea, feeding and chaperoning it for up to 12 weeks without his female partner. In Laysan Albatrosses, heterosexual parents are together at the nest for a remarkably short time—only 5–10 days out of the 230-day breeding season. Eggs are sometimes temporarily “adopted” by other birds who incubate them when the parents are away from the nest. Nonbreeding females have even been known to “join” existing pairs and regularly take turns with the parents incubating their egg. Sometimes females also lay a second egg in a stranger’s nest. Reproduction in this species is often fraught with difficulties, however. More than 20 percent of parents (both males and females) desert their nests—often when their partner fails to return for an incubation shift on time—and couples also occasionally divorce (2 percent of all pairs). Once the chicks have hatched, they are often subjected to abuse from neighboring birds, who may savagely peck, stab, bite, and occasionally even kill the youngsters if they stray too close.

Other Species

Homosexual copulations are common in another species of auk, the Razorbill ( Alca torda ), where 41 percent of nonmonogamous mountings (about 18 percent of all mountings) are between males. Up to 200 or more such mountings have been observed each season in some populations. Nearly two-thirds of all males mount other males (an average of 5 partners, sometimes as many as 16) and more than 90 percent of males receive mounts from other males. Older males participate more often than younger ones, and mountings are occasionally reciprocal. Like females, males usually resist such promiscuous mating attempts: although the mounter usually tries to achieve cloacal (genital) contact, only about 1 percent of same-sex mountings include genital contact or ejaculation (compared to 12 percent of promiscuous heterosexual mounts).

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

Birkhead, T. R. (1993) Great Auk Islands. London: T. and A.D. Poyser.

*———(1978a) “Behavioral Adaptations to High Density Nesting in the Common Guillemot Uria aalge.” Animal Behavior 26:321—31.

———(1978b) “Attendance Patterns of Guillemots Uria aalge at Breeding Colonies on Skomer Island.” Ibis 120:219-29.

Birkhead, T. R., and P. J. Hudson (1977) “Population Parameters for the Common Guillemot Uria aalge.” Ornis Scandinavica 8:145—54.

Birkhead, T. R., S. D. Johnson, and D. N. Nettleship (1985) “Extra-pair Matings and Mate Guarding in the Common Murre Uria aalge.” Animal Behavior 33:608—19.

Birkhead, T. R., and D. N. Nettleship (1984) “Alloparental Care in the Common Murre (Uria aalge).” Canadian Journal of Zoology 62:2121—24.

Fisher, H. I. (1975) “The Relationship Between Deferred Breeding and Mortality in the Laysan Albatross.” Auk 92:433—41.

*———(1971) “The Laysan Albatross: Its Incubation, Hatching, and Associated Behaviors.” Living Bird 10:19—78.

———(1968) “The ‘Two-Egg Clutch’ in the Laysan Albatross.” Auk 85:134—36.

Fisher, H. I., and M. L. Fisher (1969) “The Visits of Laysan Albatrosses to the Breeding Colony.” Micronesica 5:173—221.

Fisher, M. L. (1970) The Albatross of Midway Island: A Natural History of the Laysan Albatross. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press.

*Frings, H., and M. Frings (1961) “Some Biometric Studies on the Albatrosses of Midway Atoll.” Condor 63:304—12.

Gaston, T., and K. Kampp (1994) “Thick-billed Murre Masturbating on Grass Clump.” Pacific Seabirds 21:30.

Harris, M. P., and S. Wanless (1995) “Survival and Non-Breeding of Adult Common Guillemots Uria aalge.” Ibis 137:192-97.

*Hatchwell, B. J. (1988) “Intraspecific Variation in Extra-pair Copulation and Mate Defence in Common Guillemots Uria aalge.” Behavior 107:157-85.

Hudson, P. J. (1985) “Population Parameters for the Atlantic Alcidae.” In D. N. Nettleship and T. R. Birkhead, eds., The Atlantic Alcidae, pp. 233—61. London: Academic Press.

Johnson, R. A. (1941) “Nesting Behavior of the Atlantic Murre.” Auk 58:153—63.

Meseth, E. H. (1975) “The Dance of the Laysan Albatross, Diomedea immutabilis.” Behavior 54:217-57.

Rice, D. W., and K. W. Kenyon (1962) “Breeding Cycles and Behavior of Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses.” Auk 79:517-67.

Tuck, L. M. (1960) The Murres: Their Distribution, Populations, and Biology. Ottawa: Canadian Wildlife Service.

*Wagner, R. H. (1996) “Male-Male Mountings by a Sexually Monomorphic Bird: Mistaken Identity or Fighting Tactic?” Journal of Avian Biology 27:209—14.

———(1991) “Evidence That Female Razorbills Control Extra-Pair Copulations.” Behavior 118:157-69.

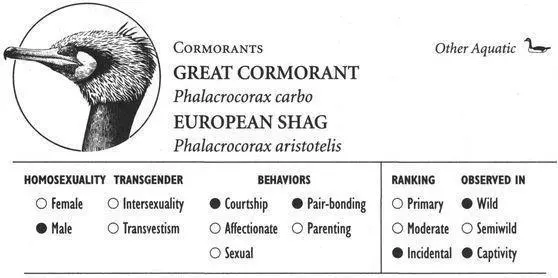

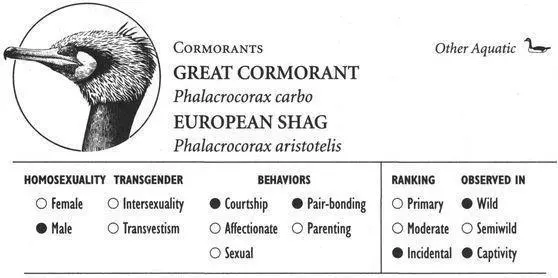

GREAT CORMORANT

IDENTIFICATION: A large (3 foot), black, web-footed bird with a white throat and white filamentary plumes on the nape. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout Europe, Australasia, Africa, and Atlantic North America. HABITAT: Seacoasts, lakes, rivers. STUDY AREAS: Shinobazu Pond, Tokyo, Japan; Amsterdam Zoo, the Netherlands; subspecies P.c. sinensis and P.c. hanedae.

EUROPEAN SHAG

IDENTIFICATION: Similar to Great Cormorant, but smaller and uniformly black, with a prominent forehead crest. DISTRIBUTION: Northwestern Europe, Mediterranean basin. HABITAT: Coastal waters; nests on cliffs. STUDY AREA: Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel, England; subspecies P.a. aristotelis.

Social Organization

Great Cormorants and Shags form mated pairs and generally nest in colonies, which may contain as many as 20,000 pairs in some populations of Great Cormorants. Outside of the mating season, these species are moderately gregarious, wandering solitarily but sometimes forming flocks.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Homosexual pairs consisting of two males sometimes form in Great Cormorants and last for up to five years (heterosexual pairs in this species are usually seasonal but may also last for several years). Male pairs often build oversize nests because both birds contribute to the construction of the nest. They often sit on the nest as if incubating eggs; similar behavior is also seen in heterosexual pairs prior to egg laying. In some homosexual pairs, one partner may use vocalizations that are typical of females (such as panting or purring sounds), or else calls that are intermediate between male and female vocal patterns. Male pairs are sometimes incestuous, composed of two brothers.

In European Shags, males occasionally court other males. As one male approaches—hopping along the rocks, pausing every now and then in an erect pose known as the UPRIGHT-AWARE POSTURE—the other male performs two displays. In the DART-GAPE, he pulls his head back and then darts it forward, at the same time opening his bill to expose the yellow interior and fanning his tail. In the THROW-BACK, he arches his neck along his back and points his beak upward while quivering his throat pouch. Sometimes the courting male will become aggressive and attack another male that approaches too closely, which also happens frequently when females approach courting males.

Читать дальше