Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Both Red and Gray Squirrels participate in a wide range of nonprocreative sexual activities. Heterosexual mounting outside of the breeding periods is common, especially in Red Squirrels. Since males have a seasonal sexual cycle that renders them infertile at these times (like females), this activity is definitely nonreproductive. In addition, penetration is usually not involved, and REVERSE mounting (females mounting males) also occurs, accounting for about 5 percent of such activity in Red Squirrels. Sexual behavior also takes place in other situations that are not optimal for breeding. Juveniles of both species often participate in mounting or sexual chases, for example, including incestuous activity between siblings or mothers being mounted by their offspring. Interspecies mating chases have also been observed between Gray Squirrels and fox squirrels (Sciurus niger).

During Gray Squirrel mating chases, as many as 34 males may pursue and harass a single female; when cornered in a tree cavity or at the end of a limb, she often defends herself by screaming and lunging at the males and then bolting away. Mounts by males result in full copulation only 40 percent of the time, as females usually escape from a male that is trying to mate with them. In addition, mating pairs are often attacked by other males, who knock the couple from the tree or savagely bite them, in some cases inflicting fatal wounds on the female. When mating does occur, the female copulates with several different males, sometimes as many as eight during a single mating bout. Mating chases in Red Squirrels can involve up to seven males at a time; a female may drag a male mounted on her for some distance or vigorously try to shake him off her back. In Gray Squirrels, sperm coagulates in the female’s vagina following copulation, forming a plug that may prevent inseminations by other males. However, females often remove these plugs, thereby preventing insemination by the male who just mated with them (while at the same time possibly allowing subsequent males to impregnate them). Young Red Squirrels sometimes suffer fatal injuries from adults during territory takeovers, and Gray Squirrel youngsters are occasionally attacked and/or cannibalized by adults. Not all adults participate in breeding: about a third of female Red Squirrels in some populations are nonbreeders, while about 30 percent of male Gray Squirrels do not mate with females each breeding season (and some individuals skip entire seasons).

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexuality/transgender

Barkalow, F. S., Jr., and M. Shorten (1973) The World of the Gray Squirrel. Philadelphia and New York: J.B. Lippincott.

Ferron, J. (1981) “Comparative Ontogeny of Behavior in Four Species of Squirrels (Sciuridae).” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 55:193–216.

*———(1980) “Le comportement cohésif de l’Écureuil roux ( Tamiasciurus hudsonicus ) [Cohesive Behavior of the Red Squirrel].” Biology of Behavior 5:118–38.

*Horwich, R. H. (1972) The Ontogeny of Social Behavior in the Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). Berlin and Hamburg: Paul Parey.

Koprowski, J. L. (1994) “Sciurus carolinensis.” Mammalian Species 480:1–9.

———(1993) “Alternative Reproductive Tactics in Male Eastern Gray Squirrels: ‘Making the Best of a Bad Job.’” Behavioral Ecology 4:165–71.

———(1992a) “Do Estrous Female Gray Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis, Advertise Their Receptivity?” Canadian Field-Naturalist 106:392–94.

———(1992b) “Removal of Copulatory Plugs by Female Tree Squirrels.” Journal of Mammalogy 73:572–76.

———(1991) “Mixed-species Mating Chases of Fox Squirrels, Sciurus niger, and Eastern Gray Squirrels, S. carolinensis.” Canadian Field-Naturalist 105:117–18.

*Layne, J. C. (1954) “The Biology of the Red Squirrel, Tamiasciurus hudsonicus loquax (Bangs), in Central New York.” Ecological Monographs 24:227–67.

Moore, C. M. (1968) “Sympatric Species of Tree Squirrels Mix in Mating Chase.” Journal of Mammalogy 49:531–33.

Price, K., and S. Boutin (1993) “Territorial Bequeathal by Red Squirrel Mothers.” Behavioral Ecology 4:144–49.

*Reilly, R. E. (1972) “Pseudo-Copulatory Behavior in Eutamias minimus in an Enclosure.” American Midland Naturalist 88:232.

Smith, C. C. (1978) “Structure and Function of the Vocalizations of Tree Squirrels (Tamiasciurus).” Journal of Mammalogy 59:793–808.

*———(1968) “The Adaptive Nature of Social Organization in the Genus of Tree Squirrels Tamiasciurus.” Ecological Monographs 38:31–63.

Thompson, D. C. (1978) “The Social System of the Gray Squirrel.” Behavior 64:305–28.

———(1977) “Reproductive Behavior of the Gray Squirrel.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 55:1176–84.

———(1976) “Accidental Mortality and Cannibalization of a Nestling Gray Squirrel.” Canadian Field-Naturalist 90:52–53.

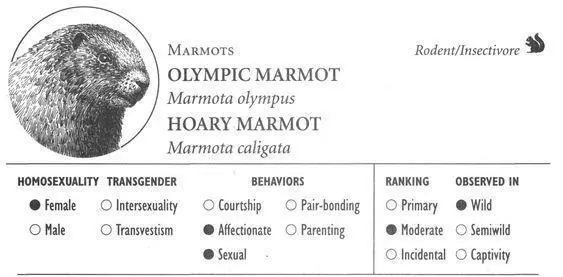

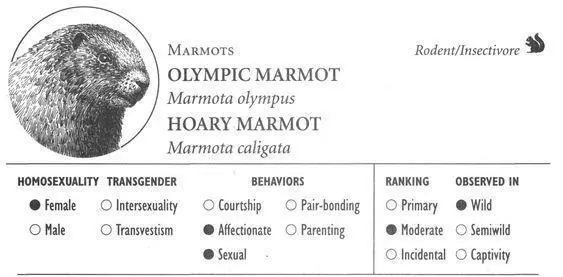

IDENTIFICATION: Woodchucklike rodents with gray, brown, reddish, or black fur. DISTRIBUTION: Olympic Peninsula, Washington; Alaska south to northwestern United States. HABITAT: Alpine slopes. STUDY AREAS: Olympic National Park, Washington; Glacier National Park, Montana; subspecies M.c. nivaria.

Social Organization

These two species of Marmots are highly social creatures that live in clusters of colonies; each colony is a series of underground burrows that is home to one male, one to three females, and their offspring. Males are generally not involved directly in parental care of their young. Occasionally an additional SATELLITE male is peripherally associated with an Olympic Marmot colony.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Olympic and Hoary Marmot females often mount other females and participate in other same-sex affectionate and sexual behaviors, especially when they are in heat. A homosexual encounter often begins with a “greeting” interaction in which the two females touch noses or mouths, or one female nuzzles her nose on the other’s cheek or mouth. She may also gently chew on the ear or neck of the other female, who then responds by raising her tail. The first female sometimes also sniffs or nuzzles the other’s genitals with her mouth. At this point she may mount the other female, gently biting her neck fur while she thrusts against her partner. The female being mounted arches her back and holds her tail to the side to facilitate the sexual interaction.

A female Olympic Marmot mounting another female

Frequency: Homosexual behavior is quite common in Marmots: in one study of Hoary Marmots, for example, three of five observed mounts by adults were between females.

Orientation: Many female Marmots that participate in same-sex mountings also mate with males. However, some nonbreeding females in Hoary Marmots (see below) probably also participate, which means that they may be involved only in homosexual interactions for those seasons that they do not breed.

Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

Although many Marmots form monogamous heterosexual pair-bonds, in some populations the majority (two-thirds) of Hoary Marmots actually live in trios consisting of one male and two females. Occasionally a “quartet” of one male and three females live together as well. Some male Hoary Marmots also seek promiscuous matings with females outside their colony, a behavior that has been termed GALLIVANTING. A form of reproductive suppression occurs in this species as well: females usually procreate every other year, but 11 percent of the time, a female “skips” breeding for two consecutive years. This is especially common in trios, where the two females alternate their skipping patterns. Males sometimes still try to mount females that are not breeding, however. Sexual activity also occurs among juveniles, including mounting of adults.

Читать дальше