van Hooff, J. A. R. A. M., and J. A. B. Wensing (1987) “Dominance and Its Behavioral Measures in a Captive Wolf Pack.” In H. Frank, ed., Man and Wolf: Advances, Issues, and Problems in Captive Wolf Research, pp. 219–52. Dordrecht: Dr W. Junk.

*Kleiman, D. G. (1972) “Social Behavior of the Maned Wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) and Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus): A Study in Contrast.” Journal of Mammalogy 53:791-806.

Lloyd, H. G. (1975) “The Red Fox in Britain.” In M. W. Fox, ed., The Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology, and Evolution, pp. 207–15. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Macdonald, D. W. (1996) “Social Behavior of Captive Bush Dogs (Speothos venaticus).” Journal of Zoology, London 239:525–43.

*———(1987) Running with the Fox. New York: Facts on File.

*———(1980) “Social Factors Affecting Reproduction Amongst Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes L., 1758).” In E. Zimen, ed., The Red Fox: Symposium on Behavior and Ecology, pp. 123-75. Biogeographica no. 18. The Hague: Dr W. Junk.

———(1979) “‘Helpers’ in Fox Society.” Nature 282:69–71.

———(1977) “On Food Preference in the Red Fox.” Mammal Review 7:7–23.

Macdonald, D. W., and P. D. Moehlman (1982) “Cooperation, Altruism, and Restraint in the Reproduction of Carnivores.” In P. P. G. Bateson and P. H. Klopfer, eds., Perspectives in Ethology, vol. 5: Ontogeny, pp. 433–67.

Mech, L. D. (1970) The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. New York: Natural History Press.

Packard, J. M., U. S. Seal, L. D. Mech, and E. D. Plotka (1985) “Causes of Reproductive Failure in Two Family Groups of Wolves.” Zeitchrift für Tierpsychologie 68:24-40.

Packard, J. M., L. D. Mech, and U. S. Seal (1983) “Social Influences on Reproduction in Wolves.” In L. N. Carbyn, ed., Wolves in Canada and Alaska: Their Status, Biology, and Management, pp. 78–85. Canadian Wildlife Service Series no. 45. Ottawa: Canadian Wildlife Service.

Porton, I. J., D. G. Kleiman, and M. Rodden (1987) “Aseasonality of Bush Dog Reproduction and the Influence of Social Factors on the Estrous Cycle.” Journal of Mammalogy 68:867–71.

Schantz, T. von (1984) “‘Non-Breeders’ in the Red Fox Vulpes vulpes: A Case of Resource Surplus.” Oikos 42:59–65.

———(1981) “Female Cooperation, Male Competition, and Dispersal in the Red Fox Vulpes vulpes.” Oikos 37:63–68.

*Schenkel, R. (1947) “Ausdrucks-Studien an Wölfen: Gefangenschafts-Beobachtungen [Expression Studies of Wolves: Captive Observations].” Behavior 1:81-129.

Schotté, C. S., and B. E. Ginsburg (1987) “Development of Social Organization and Mating in a Captive Wolf Pack.” In H. Frank, ed., Man and Wolf: Advances, Issues, and Problems in Captive Wolf Research, pp. 349–74. Dordrecht: Dr W. Junk.

Sheldon, J. W. (1992) Wild Dogs: The Natural History of the Nondomestic Canidae. San Diego: Academic Press.

Smith, D., T. Meier, E. Geffen, L. D. Mech, J. W. Burch, L. G. Adams, and R. K. Wayne (1997) “Is Incest Common in Gray Wolf Packs?” Behavioral Ecology 8:384–91.

Storm, G. L., and G. G. Montgomery (1975) “Dispersal and Social Contact Among Red Foxes: Results From Telemetry and Computer Simulation.” In M. W. Fox, ed., The Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology, and Evolution, pp. 237-46. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. *Wurster-Hill, D. H., K. Benirschke, and D. I. Chapman (1983) “Abnormalities of the X Chromosome in Mammals.” In A. A. Sandberg, ed., Cytogenetics of the Mammalian X Chromosome, Part B, pp. 283–300. New York: Alan R. Liss.

*Zimen, E. (1981) The Wolf: His Place in the Natural World. London: Souvenir Press.

*———(1976) “On the Regulation of Pack Size in Wolves.” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 40:300–341.

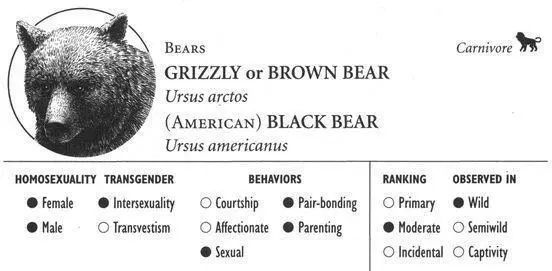

GRIZZLY BEAR

IDENTIFICATION: A huge bear (7–10 feet tall) with dark brown, golden, cream, or black fur. DISTRIBUTION: Northern North America, Europe, central Asia, Middle East, north Africa. HABITAT: Tundra, forests. STUDY AREA: Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming; subspecies U.a. horribilis.

BLACK BEAR

IDENTIFICATION: A smaller bear (4–6 feet) with coat color ranging from black to gray, brown, and even white. DISTRIBUTION: Canada and northern, eastern, and southwestern United States. HABITAT: Forest. STUDY AREA: Jasper National Park, Alberta; Prince Albert National Park, Saskatchewan, Canada; subspecies U.a. altifrontalis.

Social Organization

Grizzly Bears and Black Bears are largely solitary animals. Some Grizzly populations, however, tend to aggregate around abundant food sources such as salmon, marine mammals (stranded onshore), garbage dumps, and even insect swarms; fairly complex social interactions may develop in these contexts. The heterosexual mating system is polygamous, as both males and females generally mate with multiple partners; males do not contribute to parenting.

Description

Behavioral Expression: Female Grizzly Bears sometimes bond with each other and raise their young together as a single family unit. The two mothers become inseparable companions, traveling and feeding together throughout the summer and fall seasons as they share in the parenting of their cubs. Female companions have not been observed interacting sexually with one another, however. A bonded pair jointly defends their food (such as Elk or Bison carcasses), and the two females also protect one another and their offspring (including defending them against attacks by Grizzly males). The cubs regard both females as their parents, following and responding to either mother equally; bonded females occasionally also nurse each other’s cubs. If one female dies, her companion usually adopts her cubs and looks after them along with her own.

As winter approaches and Grizzlies prepare for hibernation, female coparents often continue to associate with one another. Foraging together late into the fall, they are apparently reluctant to end their relationship and may even delay the onset of their own sleep. Although paired females do not hibernate together, they frequently visit each other (with their cubs) prior to hibernation, staying nearby while their partner prepares her den. They also sleep together outside their denning sites during this final preparatory period and only retreat to their separate dens once the snow gets too deep. Most Grizzlies seek solitude prior to hibernating and locate their winter dens miles away from each other (and with rugged terrain separating them), but bonded females often hibernate relatively close to one another. Such females have even been known to abandon their traditional denning locations to be nearer to their coparent. One female, for example, moved her usual den site more than 14 miles to be closer to her companion. Pair-bonds are not usually resumed after hibernation, although one female may adopt her companion’s yearling offspring the following season. The average age of a bonded female is about 11 years, although Grizzlies as young as 5 and as old as 19 have formed bonds with other females. Companions may be of the same age, or one female might be several years older than the other. Sometimes more than two females are involved: three Grizzlies may form a strongly bonded “triumvirate,” and groups of four or five females have even been known to associate (sometimes also forming pair- or trio-bonds within such a group).

Читать дальше