Nonreproductive and Alternative Heterosexualities

More than 60 percent of male Lions (solitary or in companionships) do not become residents during their lives and therefore do not participate in breeding. When they do, however, Lions have extraordinarily high heterosexual copulation rates. The female may mate as often as four times an hour when she is in heat over a continuous period of three days and nights (without sleeping), and sometimes with up to five different males—far in excess of the amount required if mating were simply for fertilization. A number of other nonprocreative sexual behaviors occur in these felids as well. Lions sometimes mate during pregnancy (up to 13 percent of all sexual activity), and as much as 80 percent of all heterosexual mating in some populations may not result in reproduction. In fact, following arrival of new males in a pride, females often increase their sexual activity while reducing their fertility (by failing to ovulate). In addition, “oral sex” is a feature of heterosexual foreplay—female Lions may lick and rub the male’s genitals, while Cheetahs of both sexes lick their partner’s genitals as part of heterosexual courtship. Male Lions have also been observed masturbating in captivity: an unusual technique is used, in which the Lion lies on his back and rolls his hindquarters up above his head, so that he can rub his penis with one of his front legs.

In wild Cheetahs, incestuous activity occasionally takes place when adult males try to mount their mothers, who typically react aggressively to such advances. In fact, heterosexual relations are in general characterized by a great deal of aggression between the sexes. In Lions, heterosexual copulation is often accompanied by snarling, biting, growling, and threats, and sometimes the female actually wheels around and slaps the male. During Cheetah courtship chases, males often knock females down and slap them, and these interactions may develop into full-scale fights. When the female is not in heat, the two sexes live largely segregated lives. Family life in these species may also be fraught with violence: infanticide occurs in Lions (where it accounts for more than a quarter of all cub deaths) as well as Cheetahs. Abandonment by their mother is the second highest cause of cub mortality in Cheetahs, and mother Cheetahs occasionally eat their own cubs if they have been killed by a predator (adult male Cheetahs also sometimes cannibalize each other). However, female Lions often participate in productive alternative family arrangements amongst themselves, such as communal care and suckling of young, as well as the formation of CRÈCHES or nursery groups. Female Cheetahs also sometimes (reluctantly) adopt orphaned or lost cubs.

Sources

*asterisked references discuss homosexualityltransgender

*Benzon, T. A., and R. F. Smith (1975) “A Case of Programmed Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus Breeding.” International Zoo Yearbook 15:154—57.

Bertram, B. C. R. (1975) “Social Factors Influencing Reproduction in Wild Lions.” Journal of Zoology, London 177:463—82.

*Caro, T. M. (1994) Cheetahs of the Serengeti Plains: Group Living in an Asocial Species. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

*———(1993) “Behavioral Solutions to Breeding Cheetahs in Captivity: Insights from the Wild.” Zoo Biology 12:19—30.

*Caro, T. M., and D. A. Collins (1987) “Male Cheetah Social Organization and Territoriality.” Ethology 74:52—64.

*———(1986) “Male Cheetahs of the Serengeti.” National Geographic Research 2:75—86.

*Chavan, S. A. (1981) “Observation of Homosexual Behavior in Asiatic Lion Panthera leo persica.” Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 78:363-64.

*Cooper, J. B. (1942) “An Exploratory Study on African Lions.” Comparative Psychology Monographs 17:1— 48.

Eaton, R. L. (1978) “Why Some Felids Copulate So Much: A Model for the Evolution of Copulation Frequency.” Carnivore 1:42—51.

*———(1974a) The Cheetah: The Biology, Ecology, and Behavior of an Endangered Species. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

*———(1974b) “The Biology and Social Behavior of Reproduction in the Lion.” In R. L. Eaton, ed., The World’s Cats, vol. 2: Biology, Behavior, and Management of Reproduction, pp. 3–58. Seattle: Woodland Park Zoo.

*Eaton, R. L., and S. J. Craig (1973) “Captive Management and Mating Behavior of the Cheetah.” In R. L. Eaton, ed., The World’s Cats, vol. 1: Ecology and Conservation, pp. 217–254. Winston, Oreg.: World Wildlife Safari.

Herdman, R. (1972) “A Brief Discussion on Reproductive and Maternal Behavior in the Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus.” In Proceedings of the 48th Annual AAZPA Conference (Portland, OR), pp. 110–23. Wheeling, W. Va.: American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums.

Laurenson, M. K. (1994) “High Juvenile Mortality in Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) and Its Consequences for Maternal Care.” journal of Zoology, London 234:387-408.

Morris, D. (1964) “The Response of Animals to a Restricted Environment.” Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 13:99–118.

Packer, C., L. Herbst, A. E. Pusey, J. D. Bygott, J. P. Hanby, S. J. Cairns, and M. B. Mulder (1988) “Reproductive Success of Lions.” In T. H. Clutton-Brock, ed., Reproductive Success: Studies of Individual Variation in Contrasting Breeding Systems, pp. 363–83. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Packer, C., and A. E. Pusey (1983) “Adaptations of Female Lions to Infanticide by Incoming Males.” American Naturalist 121:716–28.

———(1982) “Cooperation and Competition Within Coalitions of Male Lions: Kin Selection or Game Theory?” Nature 296:740–42.

Pusey, A. E., and C. Packer (1994) “Non-Offspring Nursing in Social Carnivores: Minimizing the Costs.” Behavioral Ecology 5:362–74.

*Ruiz-Miranda, C. R., S. A. Wells, R. Golden, and J. Seidensticker (1998) “Vocalizations and Other Behavioral Responses of Male Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) During Experimental Separation and Reunion Trials.” Zoo Biology 17:1–16.

*Schaller, G. B. (1972) The Serengeti Lion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Subba Rao, M. V., and A. Eswar (1980) “Observations on the Mating Behavior and Gestation Period of the Asiatic Lion, Panthera leo, at the Zoological Park, Trivandrum, Kerala.” Comparative Physiology and Ecology 5:78–80.

Wrogemann, N. (1975) Cheetah Under the Sun. Johannesburg: McGraw-Hill.

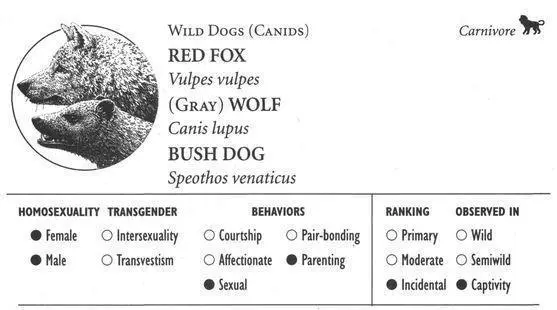

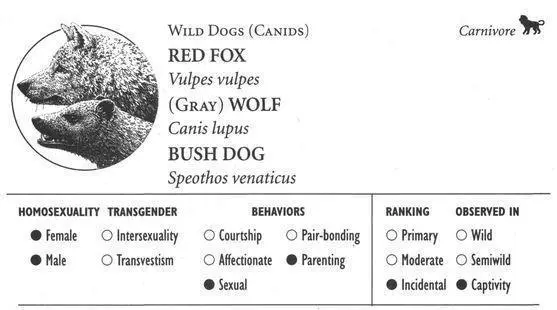

RED FOX

IDENTIFICATION: A small canid (body length up to 3 feet) with a bushy tail and a reddish brown coat (although some variants are silvery or black). DISTRIBUTION: Throughout most of Eurasia, northern Africa, and North America. HABITAT: Variable, including forest, tundra, prairie, farmland. STUDY AREA: Oxford University, England.

WOLF

IDENTIFICATION: The largest wild canid (reaching up to 7 feet in length) with a gray, brown, black, or white coat. DISTRIBUTION: Throughout most of the Northern Hemisphere. HABITAT: Widely varied, excepting tropical forests and deserts. STUDY AREAS: Bavarian Forest National Park, Germany; Basel Zoo, Switzerland; subspecies C.I. lupus, the Common Wolf.

BUSH DOG

IDENTIFICATION: A small (3 foot long), reddish brown, bearlike canid with short legs and tail. DISTRIBUTION: Northern and eastern South America; vulnerable. HABITAT: Forest, savanna, swamp, riverbanks. STUDY AREA: London Zoo, England.

Читать дальше