Damkjar, standing alongside the upper edge of the grave with the others, pointed out that the ice around Hartnell appeared quite discoloured. The ice in the centre of the block, about where Hartnell’s chest should be, was not an opaque white as with Torrington, but very brownish, even mottled.

Soon the work of exposing the body began, the warm water quickly unveiling the features of the seaman’s face. This was an overwhelming experience for Spenceley, Hartnell’s great-great-nephew, who stood close by the grave’s edge, gazing in silence at his own family history over a distance of 140 years.

There did not seem to be any major deterioration in the tissues during the two-year hiatus. One observation made in 1984 was that Hartnell’s left eye was well-preserved while his right eye appeared to be damaged, and it had been unclear whether this had happened while he lived or somehow shortly after his death. Inglefield’s reports on the exhumation that he and Sutherland had conducted in 1852 had not indicated any problem with Hartnell’s right eye. But in 1986, Beattie noticed immediately that, in addition to the shrunken right eye, Hartnell’s left eye showed some shrinkage as well. He concluded that it is likely that exposure, for even a brief period, causes changes peculiar to the eyes, leaving the rest of the external features unaffected. In other words, the exposure of Hartnell in 1852 probably induced changes in the right eye—the fact that the left eye appeared normal to the researchers in 1984 indicated that Inglefield and Sutherland probably did not expose the left side of the face. The shrinking of the left eye over the two years that had passed since its exposure in 1984 supported the theory.

As the ice surrounding Hartnell thawed, it became apparent that he was wrapped in a white shroud from his shoulders down. The damaged shirt sleeve on his right arm was exposed through a tear in the sheet and pieces of the coffin lid appeared to have been driven forcibly into his right chest wall during the 1852 exhumation. When the obscuring ice was melted higher up the arm, the tears in the shroud, shirt sleeve and undergarments were visible as scissor or knife cuts. Obviously, to fully expose Hartnell’s arm, Sutherland had had to make cuts in the shroud and clothing. This evidence showed that the investigation of Hartnell’s body in 1852 was limited to his face and right arm. It would have been too difficult and taken too much time for Sutherland to do more.

On Hartnell’s head was a toque-like hat, which in turn was resting on a small frilled pillow stuffed with wood shavings. Thawing of the ice surrounding the body continued until Hartnell was completely exposed. Nothing was moved by the group until the shrouded body had been thoroughly described and photographed. The next stage was the folding back of the shroud, which took a very long time because only the very thinnest layer of the exposed shroud and body was actually thawed and additional thawing of the fabric was required.

As Hartnell was unwrapped from the shroud his left arm was exposed, followed by his right arm. Immediately, Amy and Beattie could see that the arms had been bound to the body in the same manner as was seen on Torrington, though this time the material used was light brown wool. However, his right hand was lying on an outside fold of the binding. It was clear that his right arm had been extracted by Sutherland, who, when his examination was complete, had not tucked the hand back underneath the binding but left it lying on top.

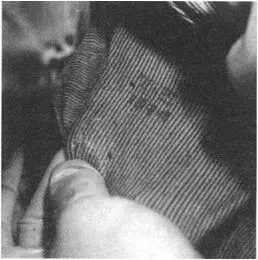

Hartnell’s blue-and-white-striped shirt was of a similar pattern to that seen on Torrington, though the stripes were not printed but woven (a more expensive material than that found on Torrington) and the design was also different from Torrington’s. It was a pullover style, and some of the front buttons were missing, the buttonholes being tied shut with loops of string. The lower portion of the shirt had two letters embroidered on it in red and the date “1844.” The letters appeared to be “TH,” and it may be that the shirt had originally belonged to John Hartnell’s younger brother and expedition companion, Thomas.

Underneath the shirt was a wool sweater-like undergarment, and beneath that a cotton undershirt. He was not wearing trousers, stockings or footwear. Beattie and Schweger were puzzled that Hartnell should have had three layers of clothing covering his upper body and nothing on below the waist. They suspected that there may have been a viewing of the body aboard the Erebus prior to burial, with the man’s lower half covered by the shroud.

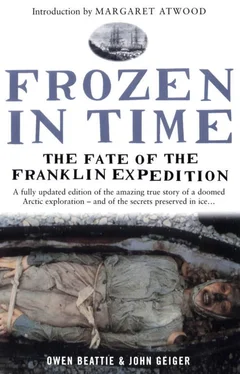

ABOVE & OPPOSITE John Hartnell: He was wrapped in a shroud, wearing a cap which, when removed, revealed a full head of dark brown hair.

BOTTOM The bottom of Hartnell’s shirt was embroidered with the date 1844 and the initials “TH,” suggesting that the shirt may have belonged to his brother, Thomas.

Hartnell’s legs and feet were slightly darkened and very shrunken and emaciated by illness and in part by the freezing. Like Torrington, his toes were tied together. In preparation for the temporary removal of Hartnell’s body for the X-ray examination and autopsy, the shroud was completely pulled back and Hartnell’s cap removed, revealing a full head of very dark brown, nearly black, hair, parted on his left. Without his hat, Hartnell lost much of the sinister look that first confronted the scientists in the summer of 1984. Instead, he appeared to be simply a young man who, for some mysterious reason, had died at the age of twenty-five on 4 January 1846.

Now began the most difficult and unpleasant phase of the exposure. Even as Hartnell lay in the coffin, apparently ready to be gently lifted out, his body was still part of the permafrost, solidly frozen to the mass of ice below. Slowly and carefully, water had to be directed underneath the body, freeing it a fraction of an inch at a time. The permafrost had a grip that would not let go without a fight. But finally, the scientists won the battle and the body was freed.

Before lifting Hartnell from his coffin, his right thumbnail was removed and samples of hair from his scalp, beard and pubic area were collected for later examination and analysis. Beattie, Carlson, and Nungaq then lifted the body out of the grave onto a white linen sheet, where it was immediately wrapped. Hartnell was carried a distance of 10 feet (3 metres) to the autopsy/X-ray tent, where Notman and Anderson prepared to take a series of X-rays while he was clothed. Still frozen to the bottom of the coffin were Hartnell’s nineteenth-century shroud, and beneath that, a folded woollen blanket. Damkjar, over the next day, struggled to remove these two items. When they were finally freed, they were handed over to Schweger for analysis and sampling.

Notman and Anderson had already set up their X-ray “clinic” inside the autopsy tent. The next order of business was the assembly of the darkroom tent. Beattie had provided them with the inside dimensions of the long-house tent months before and, using these, they had designed a unique, collapsible and portable darkroom. The structure consisted of a tubular metal frame that was screwed together; over this, a double layer of thick black plastic (cut, formed and taped together) was pulled and tucked in along the floor. On one side they had fashioned a door from a double overlap of the plastic cover, forming a light trap. Inside the darkroom, Anderson had just enough room to stand and manoeuvre around the chemical tubs. A mechanical timer was hung inside as well as a battery-operated safe light.

Читать дальше