Just before midnight on 18 June, they all gathered in Hartnell’s tent. Schweger had brought the clothing—wrapped in mylar, an inert material that would protect the clothes. Spenceley and Beattie jumped down into the grave, and Schweger passed them each item of clothing, which they placed carefully alongside the shrouded body. Once this was complete, the lid was lowered down, but, as they tried positioning it on the coffin, the two men could not get it to fit as they had found it—a layer of ice had formed on the top edge of the coffin, and this had to be chipped away before the lid would fall into its proper place. Beattie took the small chisel hammer and removed the ice within a few minutes, and the reburial continued. Spenceley and Beattie, helped out of the grave by the others, now joined the ring of researchers standing at the graveside. A spontaneous moment of silence was punctuated by the sound of the wind snapping the tent flaps and the sorrowful howling of Keena. “One hundred and forty years ago, his brother was standing in this same spot,” Beattie said at last, breaking the silence.

Slowly, the group filed out of the tent and, with hardly a word spoken, they all began to fill buckets with gravel and complete the process of reburial. At this time, none of them could fail to feel the transience of human existence and the reality of death. Exhuming Hartnell had been a hard thing to do, something very difficult to deal with. But now it was finished and, for the moment, there was relief that this one door was closing on their project. But in the tent next to them, the excavation of Private William Braine of the Royal Marines had already uncovered a surprise.

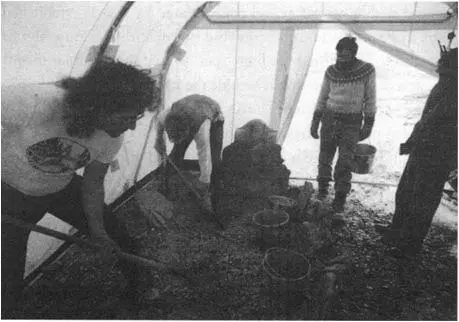

As with torrington and Hartnell’s graves, a string grid was placed over Braine’s grave. Damkjar made scale drawings of I the surface features in each square of the grid, while Spenceley, hovering on a ladder over his tripod-mounted camera, took a series of Polaroid photographs to be used during the reconstruction.

On the snow beside the grave, the crew assembled another long-house tent. This was lifted over the headboard and positioned over the grave, allowing some manoeuvring space at each side of the structure. The tent was then tied to Hartnell’s tent and the corners secured to large metal pegs driven into the permafrost.

The gravel covering the grave and filling the spaces between the limestone rocks was removed by trowelling, and, during this cleaning process, a few artefacts were found that had, over the decades, worked their way into the cracks and corners of the grave. The exact positions of these objects, mainly wood fragments and bird bones, were recorded in reference to the string grid that still covered the grave. One of the large, slab-like limestone rocks was covered with a mat of gravel consolidated by a well-established colony of mosses, and the crew did not disturb this tiny islet of vegetation. They lifted the huge rock so that the eventual reconstruction of the grave would include the micro-garden.

One of the distinctive features of Braine’s grave was the highly structured nature of its surface features. The overall impression was that it represented a crypt, and the detail of parts of the structure seemed to confirm this. A major challenge to the excavators would be the accurate reconstruction of the grave. So the rocks were removed, identification numbers and orientation indicators were penned on their undersides. These were then carried outside the tent and placed in rows on the snow, the larger rocks being used as anchoring weights for the edge of the tent.

Two hours were spent in identifying and removing nearly one hundred rocks from the surface of the grave. One of the more interesting of the large rocks was the roughly circular slab lying on the surface at the foot of the grave. Two-thirds of the exposed surface had a black colouration, which Savelle said had been applied to the grave by Penny in 1853–54. When the rock was upended, they saw that the underside was nearly completely painted black. It was apparent that this rock had at one time been standing at the foot of the grave and had functioned as the footboard seen in some of the engravings and paintings made at the site during the 1850s.

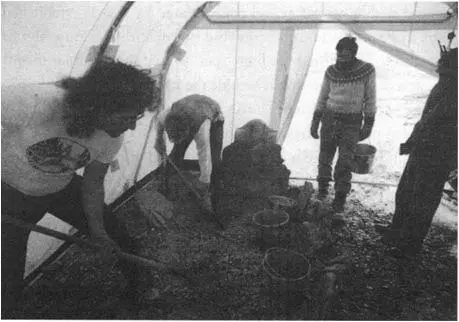

The next step, after all the rocks had been removed, was to begin the now familiar task of removing the permafrost. Kowal, Carlson, Savelle and Nungaq began digging and, eighteen hours later, encountered the first signs of Braine’s coffin. The excavation of Braine’s grave exemplified the determination of the crew, as they worked virtually non-stop for a total of 37 hours until the goal had been reached and the coffin completely exposed. Braine had been buried very deeply, down 6½ feet (2 metres) in the permafrost, and his coffin turned out to be the largest of the three—82 by 19 by 13 inches (211 by 49 by 33 cm) deep. This combination resulted in the removal of considerably more permafrost than from either Torrington or Hartnell’s graves: all four sides of Braine’s grave excavation had to be extended as the size of the coffin became obvious.

Beginning the excavation of William Braine’s grave. Left to right are Walt Kowal, Arne Carlson, Jim Savelle and Joelee Nungaq.

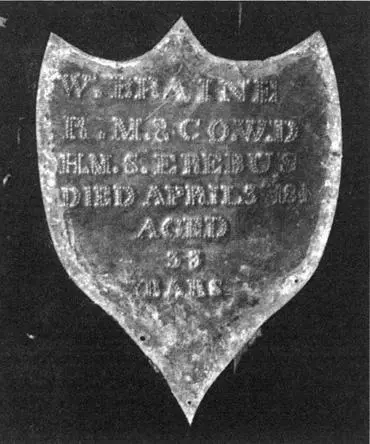

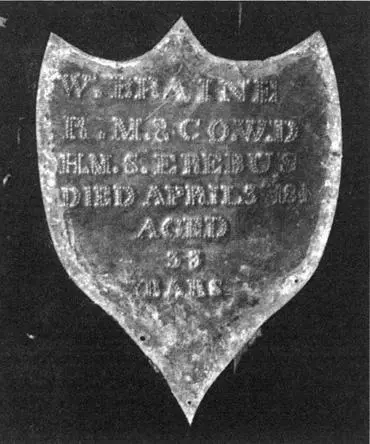

As the final inches of permafrost were picked away, the texture softened, signalling the approach of the coffin. Aware that both Torrington and Hartnell had been buried with plaques attached to their coffin lids, Kowal explored carefully the position on the lid where a plaque would have been placed. One of the thrills of archaeology is that discoveries, even those that are predictable because of previous experience, are invariably a surprise. The discovery of Braine’s plaque was no exception: the first, small exposure of the plaque revealed its completely unexpected appearance. It was copper-coloured and, as the exposure was enlarged, Kowal could see that it was metal, with the green-blue patina of copper oxidation showing on the small portion of the edge that had been carefully exposed. Kowal continued to widen the window over the plaque, which seemed to be extensive. The words punched into the metal began to emerge, and eventually the whole plaque was uncovered. It was huge, 13 by 17 inches (33 by 44 cm), and great care had obviously been taken in its preparation. The plaque read: “W. BRAINE R.M. 8 CO. W.D. H.M.S. EREBUS DIED APRIL 3RD 1846 AGED 33 YEARS.”

The copper plaque found nailed to William Braine’s coffin lid. It reads: “W. Braine R.M. 8 Co. W.D. H.M.S. Erebus Died April 3rd 1846 Aged 33 years.”

The “4” in 1846 was backwards. Everyone was thrilled by the preservation and quality of the plaque, which, while constructed differently from Torrington’s, was just as touching. With a lot of digging still to do, the plaque was covered by a piece of plastic and a thin layer of gravel to protect it during the continuing exposure of the whole coffin.

The coffin lid appeared to be in excellent condition, and Carlson felt that he could remove the lid without shearing the nails, but instead by carefully prying it with a crowbar. He began slowly, but the nails pulled free quickly and within twenty minutes the lid was loose and ready to be lifted. Carlson and Beattie, one at each end, lifted the lid slowly and gently straight up, supporting it on their arms as they passed it up to Nungaq and Damkjar, who immediately took it out of the tent.

“I see some bright red,” said Carlson, as all the researchers peered at an area of blood-red ice covering Braine’s face. Beattie glanced along the length of the coffin. He could see part of a shroud over the chest area. In direct contact with the coffin lid, it had not been obscured by the opaque ice that filled the rest of the coffin. When the thawing was started, the red colour over Braine’s face quickly took on texture and shape. It was a kerchief of Asian design with a pattern of leaves printed in black and white. As the ice melted in the rest of the coffin, the outline of the whole shroud was soon determined.

Читать дальше