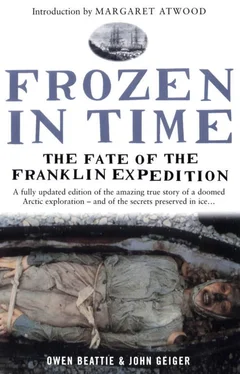

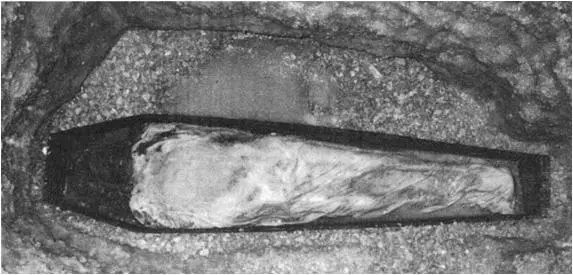

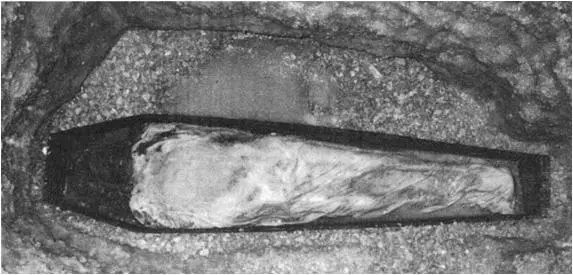

Within a few hours, the upper half of the enshrouded body was exposed. It was the most arresting vision the researchers had experienced at the site. The outline and contours of the body could be perceived in the ivory coloured shroud, but the sight was dominated by the bright red kerchief lying over Braine’s face. The vivid colour seemed so out of place deep within the grave, and the filmy nature of the material caused it to cling tightly to the face it covered, accentuating the outlines of Braine’s brow, nose, chin and cheeks; in the centre, behind small tears in the kerchief, the black oval of his partly opened mouth was visible. Poking through the tears were some incisor teeth, producing a frightening, scarlet grin that left every one of the crew transfixed.

ABOVE William Braine’s shrouded body, his face covered by a red kerchief.

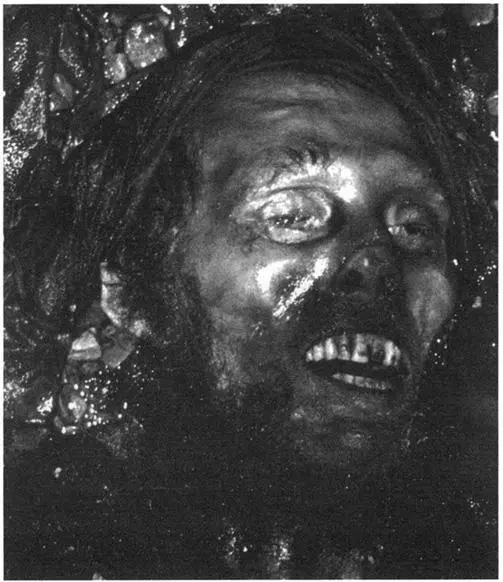

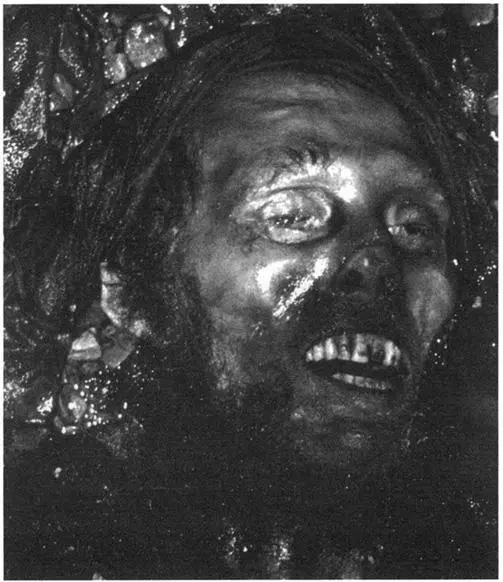

OPPOSITE The kerchief is drawn back to reveal Braine’s face.

The edges of the kerchief were still frozen deep in the recesses of the coffin; it was not yet possible to remove it to reveal Braine’s face. By pouring water into the corners of the coffin, the material slowly loosened and could be partly rolled back. As it was retracted, the face took on character and an identity.

By now, the team had been working for sixteen hours without rest. Beattie, aided by Damkjar, described the scene to the others as it became visible to him: “There’s a beard, curly and dark… got to be careful. There are the teeth, there’s an ear. It looks like he’s balding a bit.” Then Beattie stepped back to take in the view of a man who appeared severe and life-toughened, very much a nineteenth-century Royal Marine private. “Look at that. After a long day’s work it’s really something to see,” he said quietly, as if to himself.

Braine’s teeth were in very bad condition and one of his front teeth had been broken in life, causing the exposure of the pulp cavity. His lips, unlike Hartnell or Torrington’s, were pulled tightly over his teeth—perhaps the kerchief had prevented the lips from curling outwards. His nose was slightly flattened. He would have stood nearly 6 feet (181 cm) tall, and the large coffin seemed too small for him. When he had been originally placed in the coffin and the lid attached for the first time, it had pressed down onto his nose.

His eyes were deeply sunk into the eye sockets and were only one-quarter open. The eyeballs did not appear to be very well-preserved but he still had a sleepy, nearly alive appearance. A scar on his forehead indicated that he had been struck or had cracked his head against an object several years before his death. Finally, it was possible to remove the rest of the kerchief from the face, and they saw that his hair was nearly black, long and partly curly, and that he was indeed balding.

After pulling the shroud away, his shirt and right arm and hand were also exposed. “Look at that hand, it’s very well-preserved,” Beattie said. “Nice shirt, there’s not a mark on it, it looks brand new.” No sign of his left arm could be found, and the possibility that it may have been amputated was discussed. As thawing progressed, they discovered that his left arm was frozen underneath his body. Beattie at first thought Braine had been too big to be placed in the coffin with his arms in their natural position. But they later saw that it would have been just as easy to have placed his arms over the sides of his chest and still have room for the coffin lid. His body and head, too, were not positioned carefully, and one of his undershirts had been put on backwards, leading them to conclude he was placed hastily in the coffin.

Thawing the body was again a matter of pouring warm water over the frozen sections. In the cold of the grave the warm water would send up clouds of steam filled with the pungent smells of wet wool and cotton. Hours of this smell took its toll on some of the crew and the emotional strain of the work drained them all. Braine, being buried so deeply, was in colder ground, and the ice would not yield without a battle. They had tremendous difficulty in thawing the portions of the clothing and shroud frozen to the bottom of the coffin, which trapped Braine within it. Warm water poured directly onto the material seemed to have little effect, and the team struggled for eighteen more hours before they were able to free him from the ice. Even then, they had to cut the clothing up the small portion of exposed back and lift him, not only out of the coffin, but out of his clothes as well. Beattie and Amy then eased him up to the side of the grave, handing him to Savelle and Kowal, who positioned him on a plastic sheet.

Immediately noticeable was the extremely emaciated appearance of this man—literally a skin-covered skeleton. Braine would have weighed less than 88 pounds (40 kg). He must have been extremely ill during his final days. Every rib could be counted and it was possible to identify features on his hip bones. His face also reflected his condition, the skin drawn taut over the cheeks and eye sockets. His limbs had a spidery appearance; so thin were his arms that his hands appeared very large. For Beattie, lifting this frail and lifeless man up and out of his grave, coming as it did after such tremendous effort to free him, was the most difficult aspect of his work on Beechey Island. The strained faces of the others illustrated that he was not alone in these feelings.

Exhausted though the team was, Braine was immediately wrapped in a sheet and carried across to the X-ray tent. Notman and Anderson, who had been sleeping after their difficult work on Hartnell, were roused so they could begin their work. The X-raying of Braine was carried out much as it had been with Hartnell, though the situation was quite different as Braine had not had a previous autopsy. Both worked continuously for nearly twelve hours until the X-raying was completed.

Before the others could rest they still had to remove Braine’s clothing from the coffin for Schweger to analyze. With the body removed, thawing accelerated and the job was completed in an hour. During the initial thawing of the foot-end of the grave, Carlson thought he detected a different kind of fabric peeking out just below the shroud-wrapped feet. Not until the body had been removed and further thawing of the shroud had taken place was his observation confirmed. Rolled up and placed under Braine’s feet were a pair of stockings. These were quite large and appeared to be of a heavy material, and one had a hole in it. The thawing and removal of the shroud and kerchief were left for the following day. Beattie, Kowal, Savelle, Amy and Damkjar wandered back to the cook tent, had a wash outside and went in for food and drink. They were then able to have a brief rest before returning to conduct the autopsy.

When they gathered again, all suffered terrible headaches and dizziness. Some felt they would be physically ill. They came to the conclusion that they were suffering the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning from the two stoves that burned continuously during the removal of Braine from his coffin. Although the tent flap had been tied open and a breeze had blown through during the work, the fumes had gathered in the grave pit, creating the problem.

When Amy and Beattie entered the X-ray/autopsy tent to begin their work, Notman pointed out a series of lesions on Braine’s body: on the left and right shoulders, in the groin area and along the left chest wall. These lesions involved the skin and in some cases the tissue and muscle below. Close inspection revealed teeth marks. Notman and Amy agreed that rats must have attacked the body while it had rested aboard the Erebus, prior to burial.

Читать дальше