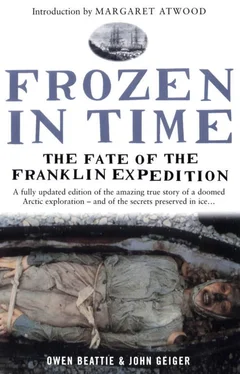

The sutured autopsy incision found on John Hartnell, dating to the autopsy conducted on his body during the expedition in early January 1846.

The standard incision in an autopsy performed today is “Y”-shaped, with the arms of the “Y” extending down from each shoulder and meeting at the base of the sternum (breastbone). From this point, the incision continues down to the pubic bone. In the case of Hartnell’s autopsy, however, the incision was upside down: the arm of the “Y” originated near the point of each hip, meeting near the umbilicus (belly button) and extending up to the top of the sternum. Given that the procedures for autopsy technique in the mid-nineteenth century are not well represented in today’s scientific literature, Beattie wondered if the incision indicated that the surgeon was concentrating on the bowel or whether this was the habitual procedure for autopsy followed by the surgeon. Amy was later able to reconstruct, step by step, what the original pathologist had done. The extent and direction taken during this first autopsy would provide clues to the suspicions held by the surgeon relating to the cause of death.

That an autopsy had been done solved the mystery of the strange X-rays: the surgeon of the Erebus had removed the organs for examination, then replaced them in one mixed mass. Not surprisingly, this disrupted anatomy resulted in a meaningless collection of soft-tissue detail in the first X-rays taken by Notman and Anderson. Also, the brownish discolouration seen in the ice when the lid was first removed probably resulted from blood and other fluids seeping out of the incision when water filled the coffin during the summer of 1846.

After Notman and Anderson had completed a second series of X-rays, a process that took another six hours (for a total of fourteen hours of X-raying), they retired for a well-deserved rest, but not before a slightly hair-raising experience. The X-raying had continued into the late hours, and most of the crew had retired to their tents. Savelle and Nungaq were sitting in the kitchen tent talking. Beattie was in the autopsy/X-ray tent, more as company for Notman and Anderson than as help. Keena, the dog brought along to serve as a watch for polar bears, was tethered outside the kitchen tent and could be heard whining in her familiar, annoying way. Suddenly Keena stopped whining—unusual in itself. But then she barked madly. The three men in the autopsy/X-ray tent looked at each other. They had never heard her bark before and they knew that there had to be a good reason: a bear. Then they heard the “pop pop pop” of rifles being fired and, off in the distance, voices shouting, “Bear, bear in camp!” Beattie reached for the rifle he had brought down to the tent and slowly stuck his head out. The tents over the graves and the autopsy/X-ray tent were separated from the main grouping by about 330 feet (100 metres), and, peering round the edge of Braine’s tent back towards the main camp, he saw a bear standing in the open space. Notman and Anderson were now beside Beattie, sizing up the situation. Beattie had Kowal’s gun, one with which he was not familiar—and sure enough the bolt jammed twice, but the third and final bullet went into the chamber cleanly. Notman, looking around for some other weapon, grabbed a shovel. Anderson had his camera. So armed, the three stayed behind Braine’s tent out of sight of the bear, which soon became annoyed at the noise of guns and people. It ambled off, angling towards the beach. Passing downwind of the graves, just 65 feet (20 metres) away, it then caught the scent of the three and of John Hartnell. As it paused with its nose in the air, Beattie thought, “Oh, brother, it’s gonna come this way.” But then he heard “twang twang twang,” as three bullets ricocheted off the gravel beside the bear, forcing it back in slow retreat, and the crisis ended as the bear ambled down the beach and out onto the ice. From that point on during the summer, someone always stayed outside keeping watch with the dog. From the bear tracks in the snow, Nungaq was able to determine that it had come in off the ice close to the kitchen tent, chased some gulls, wandered up to the food cache beside the kitchen tent and then saw the dog and decided to sniff it out. No wonder Keena had barked: when people started to pop their heads out of tents to see what the commotion was all about, the bear and the dog were nose to nose. Keena was lucky. Notman, Anderson and Beattie were lucky. It may have been close to the end of a long day, but none of the crew was ready for sleep now.

With the X-raying complete, Amy and Beattie, dressed in green surgical gowns, white aprons and blue surgical caps, began the autopsy. Hartnell was first measured and weighed. He was taller and heavier than Torrington, at 5 feet 11 inches (180 cm) and 99 pounds (45 kg). Amy then reopened the inverted “Y” incision by cutting the original sutures. He noted that several knife cuts were made on the surface of the chest plate before the ribs had been successfully divided during the original autopsy. It soon became obvious that Franklin’s surgeons had not focussed their attention on the bowel, as their incision suggested; it seemed they believed the cause of Hartnell’s death concerned the heart and lungs. In the earlier autopsy, Dr. Goodsir had removed the heart with part of the trachea. He would first have held the heart up to look at its apex for signs of disease; then he made two cuts, one each into the right and left ventricles, to look at the valves. When he had finished with the heart, he dissected the roots of the lungs to look for evidence of tuberculosis and made a few cuts into the liver looking for confirmation of the disease. Hartnell’s bowel was untouched. On completion of the autopsy, Dr. Goodsir replaced Hartnell’s chest plate (the anterior portion of the ribs and the sternum) upside down. The original autopsy turned out to have been a cursory one that could have been conducted in less than half an hour. During his investigations, the surgeon of the Erebus would have found confirmation of tuberculosis of the lungs. Once observations about the original autopsy had been completed, Amy began his own much more detailed investigation. Beattie labelled the sample containers and sealed the samples handed to him by Amy, while Spenceley photographed the proceedings.

First, any frozen water from inside the body was collected, as these fluids would have come from the tissues. Then, after sterilizing his surgical instruments in the open flame of a naphtha stove, Amy cut a frozen piece from each of the organs and placed these samples in a sterile container that was promptly sealed and kept frozen in a cooler. The samples would later undergo bacteriological analysis in the laboratory. Other samples of organs and tissue were then taken and placed in preservative, to be later studied under a microscope. Amy occasionally made observations about the condition of Hartnell, such as the state of blood vessels: “Vessels don’t contain blood, they contain ice and the ice is clear.” Many of the organs were found to be in a fair state of preservation, though the brain had turned to liquid. Finally, bone was cut with a surgical saw from the femur, rib, lumbar vertebra and skull. From start to finish, when Amy resutured the original 1846 incision, the autopsy took the three men nine hours to complete. It had been very thorough.

Everyone was exhausted, yet work was continuing nearby in Braine’s tent in preparation for his exposure. Hartnell’s body was tightly wrapped in the autopsy sheet and carried into his own tent. When Schweger finished documenting the Hartnell fabrics, the group arranged for his reburial. The blanket was repositioned in the bottom of the coffin and the original shroud laid back in position. His body was passed down into the grave and placed in the coffin. The shroud was then closed over him, and it was soon time for their final moment with the young sailor.

Читать дальше