Beattie was starting his 1986 field season earlier than in 1984, in order to avoid the problem of water run-off from melting snow. But as the temperatures remained below freezing in June and a brisk wind swept across the island for a good number of days, heightening the cold, the investigators had to endure additional hardships.

Each of the crew quickly set to work establishing camp, consisting of the usual array of individual and communal tents, with one new addition, a 16-foot-tall (5-metre) flagpole, where the bright red-and-white Canadian flag snapped in the near constant winds alongside the flag of the Northwest Territories. During this work, however, Beattie’s mind was fixed on something else. For two years, one question had nagged him. It was a question posed by almost everyone he had talked to about the research on Beechey Island: Was there any guarantee that the bodies of John Torrington and John Hartnell were again encased in ice after their 1984 reburials? The theory that the summer meltwater would trickle down into the filled-in excavations, seep into the coffins and subsequently freeze was a good, logical one. But Beattie wondered if the process were so simple. The 1984 exhumation of John Torrington was final and complete; there could be no verification of the theory there. However, uncovering John Hartnell, exposed once in 1852 and again in 1984, would soon answer the question.

A tent was again erected over Hartnell’s grave to protect the exhumation process from the elements. As before, digging was extremely difficult. The exposure of Hartnell’s coffin required twenty-four hours of continual digging by Kowal, Carlson, Savelle and Nungaq, a process that had now become almost mechanical. One person would labour with the pickaxe until either the pain in his hands or the exhaustion in his arms required rest. The loosened ice and gravel would then be shovelled into buckets by one or two of the excavators, lifted out of the grave to another of them and finally dumped on the growing pile of “back-dirt.” Conversation between the excavators began with recollections of previous archaeological digs, especially those of 1984, but as the hours passed, the relentless sound of the pickaxe, broken regularly by the rasping, fingernail-on-blackboard sound of the shovel pushing into resistant gravel and ice, eventually won out.

When the coffin lid was finally exposed and the limits of the coffin identified, the group took a long overdue rest and waited for the arrival of the team of specialists. To this point, the excavation was a replay of 1984. But the next step, the removal of the coffin lid, though also done in 1984, would this time provide an answer to the question of the refreezing of the bodies. They were therefore poised at the true beginning of the 1986 investigation.

During the break in the exhumation work, Beattie and Damkjar returned to the food-tin dump for a more detailed survey than the one they had conducted in 1984. Two days were spent thoroughly documenting what was left of the tins. Out of the original 700 or so, fragments of fewer than 150 remained. Tins are a very transportable, recognizable and desired artefact for amateur archaeologists and collectors, and, over the decades, people had been depleting the information pool represented by the containers. None of those remaining was complete and most were badly fragmented. But all portions of the tins were represented, including the soldered seams.

The area of the tin scatter was gridded with string and tied in to a datum point. Each square of the grid was photographed and searched, and every tin fragment located and described. All of the larger pieces and those with particularly good features were individually photographed. Samples of “ordinary” tins were collected for later study, along with some tins that were particularly good examples of poor soldering and manufacture.

On the second day of work at the can dump, Beattie and Damkjar were interrupted by Nungaq, who had been out hiking on the ice of Union Bay during the break in the digging. He came walking quickly along the spit towards them, his dog Keena held tightly by her chain. “There’s a bear coming,” he said, as he trotted up the rise of the mound. Pointing west, he continued: “Look, over there, it’s coming right for us.” Little interest in the tins remained, as Beattie and Damkjar squinted out over the bright field of ice. Then Beattie saw it. The bear’s head was lowered and it did not appear to be moving at all, though its body was swaying slightly from side to side. From this quick glimpse, Beattie recalled an important lesson. He remembered when he was a student pilot and his instructor had lectured him: “If you spot another airplane coming your way and it appears to be moving, you’re safe—just keep your eye on it. But if that plane looks like it is standing still, watch out, because it’s coming straight for you.” A strange thing to recall at this particular time, but the rule still applied. Although the bear was a good distance away, perhaps a mile, it looked awfully big. And within minutes they were all heading back to camp, cameras swinging from their necks, clutching notebooks, tripods and rifles. They did not want to leave either expensive camera equipment or their collected data at the tin dump for the bear to play with, so they had filled their arms with everything taken to the site. Halfway back to camp, they turned to see the bear crossing the spit with a slow, purposeful gait. They breathed easier when they watched the bear stop for a moment to test the air, then move on, heading across Erebus Bay to Devon Island.

The Twin Otter carrying Amy, Notman, Anderson and Schweger at last swept over the camp. Beattie noticed right away that skis had been strapped onto the tundra wheels of the aircraft. The thin layer of snow on the island made landing there impossible; the plane would have to land offshore, on ice-covered Erebus Bay. That meant that the heavy load of equipment on board, over half of the 3,300 pounds (1,500 kg) of equipment to be used during the research, would have to be carried across the ice and up the beach to their camp. After brief greetings, the eleven-member team watched the Twin Otter leave, then spent the next two hours at that difficult task.

Exhumation work resumed with the digging of a work area adjacent to the right side of the coffin. This exposed the coffin’s side for the first time, and immediately, something of interest was discovered: three “handles” were found spaced along the side of the coffin wall. However, these were not real handles like the ones on Torrington’s coffin, but symbolic representations made out of the same white linen tape that decorated the edges of the coffin.

As in 1984, the team used heated water to accelerate the thawing process. There was no running water on the island, so Kowal developed a highly efficient method of melting snow, providing a constant, though meagre, water source. The water was heated, two buckets at a time, on naphtha stoves located in the adjacent autopsy/X-ray tent. When ready, Kowal carried the buckets across to Carlson and Nungaq, who would slowly pour the water over the dark-blue-wool-covered coffin. When too much water had accumulated in the bottom of the grave, making work virtually impossible, an electric sump pump was lowered in. The water drawn out of the grave was then directed through a hose away from the excavation area. It seemed to Beattie that the thawing was much more difficult than it had been in 1984; the time of year probably accounted for the difference. Although they did not test the temperature of the permafrost in 1984 or 1986, it seemed that at every depth it was colder in June than in August.

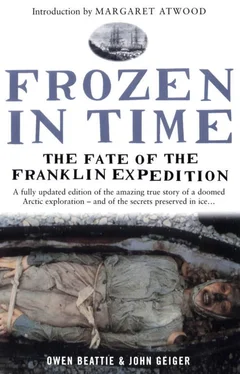

After photographs of the cleaned coffin were taken and it was measured (79 by 19 by 13 inches/203.5 by 48 by 33 cm deep), the delicate task of loosening and removing the already damaged lid was started. When at last it was lifted, Beattie and Carlson could see immediately that Hartnell’s right arm area and face, both exposed in 1984, were again completely encased in ice. “Well, the water flowed back in, didn’t it?” Beattie said. The question had been answered. Standing by Hartnell’s ice-protected body, Beattie thought about the condition of John Torrington only a few steps away. He was now satisfied that the young petty officer was again suspended in time by the very process that had allowed them a brief, privileged glimpse in 1984.

Читать дальше