With the reconstruction of the surface features of Hartnell’s grave complete, the crew readied to leave the island. The plane would come for them in two days—plenty of time to pack, clean the site and do some more exploring. It was also a time to take in all that they had experienced. Kowal and Ruszala left for a 22-mile (35-km) hike to Cape Riley and back, while Damkjar and Carlson headed up onto the headland of the island.

Beattie spent the time alone, staring out at Erebus Bay. He remembered an account he had read about an earlier visit to Beechey Island, a visit made by the explorer Roald Amundsen in August 1903. Amundsen, on his attempt to sail the Northwest Passage, had stopped at Beechey Island to pay tribute to Franklin. Amundsen later wrote in his narrative, The North West Passage, that he experienced a “deep, solemn feeling that I was on holy ground.” He imagined the bustle of activity that had transpired as the Erebus and Terror prepared to winter here, and also pondered the causes of the deaths so early on in the expedition: “The dark outlines of crosses marking graves inland are silent witnesses before my eyes as I sit here. The spectre of scurvy showed itself for the first time, and claimed, if not many, yet several lives.” Amundsen’s party then “re-erected the only gravestone that had fallen down.” With his small vessel Gjoa anchored in Erebus Bay, Amundsen grappled with the decision of what route to take. He made the correct one, becoming the first man to successfully sail the elusive passage, though he wrote of the Franklin expedition: “Let us raise a monument to them, more enduring than stone: the recognition that they were the first discoverers of the Passage.” As Beattie reflected back on his summer’s experience, he did so with a growing feeling that the very freshness of the Franklin sailors’ bodies guaranteed the success of his own expedition. Little doubt remained that important new insights into the fate of Franklin and his crews would surface during the months of laboratory work ahead.

The team’s final day on Beechey Island, 26 August 1984, was warm and sunny. The tents came down quickly and the gear was carried down by the graves. The gravel in the camping area was smoothed over and some final bits of paper picked up. Beattie then radioed the Polar Shelf base manager in Resolute Bay, and the plane departed to pick them up. Some final photographs were taken of the site and they set up a tripod to take a group picture. As they were doing this they could just make out the sound of a plane to the west. In the Arctic, there is a sixth sense about airplanes: people will suddenly look up and say, “There’s a plane,” and everyone will stop what they are doing and listen intently. Usually nothing is heard, but no one doubts that an aircraft is coming. Within a few brief seconds, the unmistakable sound of the engine is heard by all.

Soon a Twin Otter hissed by overhead. Everyone waved, the cameras came out and all watched as the plane made one pass, then circled and landed.

Sitting on the left side of the plane, Beattie looked out at the graves. During the previous two weeks, he had taken hundreds of photographs of all three and had looked into two of them, yet he felt strangely compelled to take one more photograph through the fogged and scratched window and spinning propeller of the Twin Otter. After pressing the shutter, and before he could wind the camera for a second picture, the plane began to roll. And with a roar and two jarring bumps, the plane was up and away. Seconds later, they were out over Union Bay, turning towards Cornwallis Island, visible to the west. Within forty-five minutes they were all sitting in the eating area of the Polar Shelf facilities in Resolute Bay, sipping coffee and eating a splendid home-cooked meal the staff had put aside for them. The security and hospitality of the Polar Shelf in Resolute was in marked contrast to the small campsite that had been their home. Already, the emotions attached to Beechey Island were fading. Priorities now turned to showers, laundry and news of the outside world. The jet from the south would arrive the next day, and that meant going home. The season had been a success, but still more exciting discoveries awaited them in their laboratories in Edmonton.

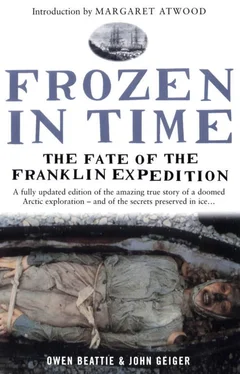

Essentially, the body of John Torrington was that of a mummy. What made it so different from mummies recovered from other archaeological sites in the world, however, was the amazing quality of preservation.

When archaeologist Howard Carter opened the three coffins of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamen in the Valley of the Kings, he found the monarch’s body in a very bad state of preservation. Dr. Douglas Derry, the anatomist who examined Tutankhamen’s mummy, wrote a detailed report describing the charred and discoloured remains. The report outlined the damage done through the embalming process and through time: “the skin of the face is of a greyish colour and is very cracked and brittle… the limbs appeared very shrunken and attenuated.”

Even mummies better preserved than Tutankhamen, whether embalmed in preparation for burial or intentionally desiccated by exposure to sun or air, have still suffered major alteration to the appearance, colour and detail of their soft tissues.

Of course, the nature of burial can, on rare occasions, result in the unintentional whole or partial preservation of an individual. Some of the best-preserved human remains from antiquity have been found in peat bogs in several locations in northwestern Europe. In some cases the acids of peat bogs have kept human bodies largely intact not for hundreds but for thousands of years. But those same acids badly discoloured the “bog people,” as they are known, leaving skin “as if poured in tar” and hair bright red, and helping to decalcify the bones. Another natural means of preservation can result from cold temperatures and lack of moisture. In 1972,500-year-old mummified human remains, including that of a child, were discovered at Qilakitsoq, Greenland. All of these mummies, however, were rigid and inflexible, the drying and hardening of the tissues having locked the body forever into the position in which it was buried.

Undoubtedly the most amazing aspect of the Beechey Island research was the discovery of the near-perfect preservation of soft tissue. In effect, the unbroken period of freezing from early 1846 to 1984 suspended any major outward appearances of decay, allowing John Torrington to look very much as he had in life, right down to the flexibility of the tissue. Even when samples of Torrington’s tissues were studied by microscope, some of them looked recent in origin. Other clues, however, did reflect the lengthy period of freezing. Details of internal cellular structure were commonly missing, and in most tissues the cells were also partly collapsed. Preservation seemed also to vary within the individual. For example, microscope slides made from bowel samples collected from Torrington appeared as if they were taken right out of a textbook on modern human histology or pathology, while slides made from his other organs showed considerable post-mortem change and loss of detail.

Still, Torrington’s condition was highly unusual, even for a body preserved in ice. Normally, the fats in the organs and muscles of humans or animal cadavers (whether encased in ice, submerged in water or located in a high-humidity environment) are transformed into adipocere, the so-called “fat wax” or “grave wax.” This ivory-white-coloured adipocere has a soapy, cheese-like consistency and a pungent, pervasive and unforgettable smell. While the superficial shape of the organ is maintained under the right conditions, over decades the adipocere changes, ending with desiccation as a firm, though crumbly, body mass, without internal structure. However, Torrington displayed a totally different morphology.

Читать дальше