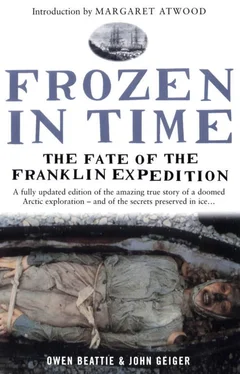

Equally intriguing, a similar level of preservation was later observed in the 5,300-year-old iceman found in the Otztal Glacier of the Italian Alps in 1991. And in meetings and discussions between Beattie and Dr. Konrad Spindler of the University of Innsbruck, the lead investigator of the Tyrolean iceman project, it was verified that there is a relationship between the mummification process and the temperature at which the bodies are stored. As Spindler wrote of his discovery: “Transformation into fat wax takes place at temperatures around 0°C [32°F]; mummification with gradual dehydration, on the other hand, occurs at lower temperatures, from about five degrees below zero on, in which case permafrost conditions represent the decisive requirements.”

LABORATORY RESULTS of the autopsy on John Torrington painted a picture of a young man wracked with serious medical problems. Unfortunately, despite careful study of the organ samples by Roger Amy at the University Hospital in Edmonton, a specific cause of death could not be established.

What was most obvious at the time of the autopsy were Torrington’s blackened lungs, a condition called anthracosis—caused by the inhalation of atmospheric pollutants such as tobacco and coal smoke and dust. Also, his lungs were bound to the chest wall by adhesions, a sign of previous lung disease. Microscopically visible destruction of lung tissue identified emphysema, a lung disease normally associated with much older individuals; evidence of tuberculosis was also seen. Amy’s interpretation of the adhesions, and of the presence of fluid in the lung associated with pneumonic infection, suggested to him that pneumonia was probably the ultimate cause of death.

However, it was in the trace element analysis of bone and hair from Torrington that the probable underlying cause of death was found. Atomic absorption analysis of Torrington’s bone indicated an elevated amount of lead of no—151 parts per million (the modern average ranges from 5–14 parts per million). Although not as high as those found in the Franklin crewman from Booth Point, the level of bone lead was still many times higher than normal. Torrington would have suffered severe mental and physical problems caused by lead poisoning and, so weakened, finally succumbed to pneumonia. (One theory as to why the Booth Point skeleton had greater lead contamination is that the Franklin sailor found in 1981 lived more than two years longer than John Torrington, and was thus exposed to lead on the expedition for a longer period.)

Most vital to Beattie’s investigation, however, were the results of a trace level analysis conducted on hair. (Four-inch-/10-cm-long strands of hair from the nape of Torrington’s neck had been submitted for laboratory analysis to determine if Torrington had been exposed to large amounts of lead. The hair was long enough to show levels of lead ingestion throughout the first eight months of the Franklin expedition.) For Beattie was astounded by the results of the carefully controlled test. Lead levels in the hair exceeded 600 parts per million, levels indicating acute lead poisoning. Only over the last inch or so did the level of exposure drop, and then only slightly. This would have been due to a drop in the consumption of food during the last four to eight weeks of Torrington’s life, when he was seriously ill.

By combining information gathered from the manner of Torrington’s burial, the new information about his physical condition and illnesses and period accounts of similar burial services conducted in the Arctic, it was now possible for Beattie and his research colleagues to re-create Torrington’s final days, death and burial with some accuracy.

There is no question that during the last couple of weeks of life, John Torrington would have known his time had almost come. Beattie’s studies revealed that the petty officer’s health had never been good, but in late December 1845, it was different. John Torrington was dying. He had boarded the Terror eight months earlier, doubtless filled with high hopes. He must have been outwardly healthy when the expedition made its last contact with whaling vessels in late July and early August, or he would have been sent home. Indeed, sickness seems to have struck in September, about the same time that Franklin’s two ships anchored for the winter some 660 feet (200 metres) off the northeast section of Beechey Island.

It was a slow-moving and lingering illness. The early symptoms of the deadly combination of emphysema and tuberculosis with lead poisoning would have included loss of appetite, irritability, lack of concentration, shortness of breath and fatigue. Torrington probably continued to work until mid- to late-November, when he would have been sent to the sick bay. The lack of any bed sores on his body shows that during much of December, on the advice of the ship’s physician, Torrington would have taken slow walks below deck several times a day. There he could talk with friends and, from time to time, before the illness became acute, look out through the gloom of the Arctic winter at the barren, snowswept rock of Beechey Island.

Torrington’s physical condition would have worsened dramatically over Christmas. His behaviour would have grown unpredictable, with dramatic mood swings that must have caused grave concern to surgeons Alexander Macdonald and John Peddie. For there was no way that these men, with the knowledge and equipment of their time, could have known the true nature of his illness. All they would have been able to do for Torrington through most of the course of his disease was to keep him well-fed, likely relying more heavily on tinned provisions as the preferred food. Yet, despite their attention, his weight would have continued slowly dropping to the point of malnutrition. Then, probably during the last days of 1845, Torrington developed pneumonia, a serious blow considering his already diminished state of health. He would never again look out into the Arctic night.

Sometime in the days immediately preceding death, Torrington would have given his few possessions to someone who would promise to return them to his father and stepmother when the expedition had sailed through the Northwest Passage into the Bering Strait and returned triumphantly to England. Towards the end, the twenty-year-old sailor would have fallen into a delerium, then suffered a series of convulsions before dying on New Year’s Day.

News of the expedition’s first loss would likely have spread quickly through the crew of the Terror, and the surgeon would have notified Captain Francis Crozier. Within minutes, the men of the Erebus, including Franklin, would have been informed of John Torrington’s death. The surgeons probably debated the cause, going over the protracted and progressive nature of his disease before concluding it was pneumonia complicated by a history of tuberculosis. There was no call for an autopsy. Torrington’s body was then carefully cleaned and groomed below deck, where the temperature probably hovered continually around 50°F (10°C). It was 1 January, and his death surely cast a shadow over any New Year celebrations.

After Torrington’s body was washed, he was dressed in his shirt and trousers. The two surgeons took care in binding his limbs to his body: one of them wrapped a cotton strip round the body and arms at the level of the elbow, tying a bow at the front; the other quickly tied cotton strips round the big toes, ankles and thighs.

Above deck, where the ship had been draped with a canvas cover to keep out the snow and some of the cold (the temperature would still be around 14°F/-10°C), the carpenter Thomas Honey and his mate Alexander Wilson began carefully constructing the coffin, Macdonald having provided them with Torrington’s measurements. They used a stock timber, mahogany, measuring ¾ inch (1.9 cm) thick by 12 inches (30 cm) wide. The lid and coffin bottom were each constructed of three pieces: a long central piece with shaped sections attached by dowels to each side. The box was constructed of the same type of wood; the curves at the shoulder produced by kerfing (a series of parallel cuts made across the inside width of the board, allowing it to be bent without breaking). Square iron nails were used to secure these sections together.

Читать дальше