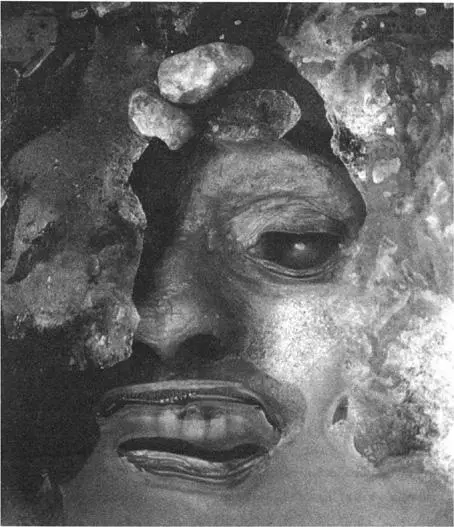

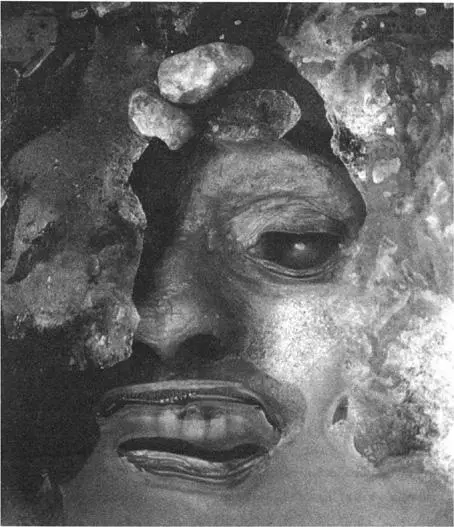

“This guy is spooky,” Kowal said while continuing the exposure of Hartnell, “the quintessential pirate. This guy is frightening.”

The others watched in silence as the face was finally completely exposed. Perhaps the emotional drain of their work with Torrington was only now taking its toll. As with Torrington, they were shaken by the second face that was emerging from the rock-hard ground of the island. Shaken, but in a different way.

Whereas Torrington had embodied a youthful, tragic innocence, John Hartnell reflected the harsh realities of death and suffering in the Arctic: his was the face of a sea-hardened nineteenth-century sailor. His right eye socket appeared empty and his lips were rigidly pursed, as if he were shouting his rage at dying so early in his adventure. John Hartnell’s last thoughts and the intensity of the pain he suffered during those final moments of life had been captured—literally frozen—on his face.

His features were tightly framed by a cap, a shroud drawn up under his red-bearded chin and the contours of melting ice on either side. A lock of dark hair could be seen below the rim of the cap; unlike the right, his left eye appeared normal. “I wonder why there is such a difference in the preservation of the eyes,” Beattie mumbled, as each took a turn to examine Hartnell. “Was the eye injured before his death? Was it diseased?” Answers to the countless questions would have to await their planned return to Beechey Island.

Besides the face, only the clothing covering the right forearm was exposed. The body had been covered in a shroud, or sheet. A portion of the shroud and the underlying shirt sleeve of his right arm had been torn by the pickaxe used during the original exhumation. There also appeared to be damage to the arm itself. The total time of Hartnell’s exposure was close to twelve hours.

The first view of John Hartnell.

Later, back in the labs and libraries of Edmonton, Beattie would begin piecing together a solution to the mystery of Hartnell’s disturbance. Sir Edward Belcher was the first to dig into the graves in October 1852, but, discouraged by the resistant permafrost, his men gave up after excavating only a few inches. A month later, members of a privately funded search expedition exhumed Hartnell. The leader of the expedition was Commander Edward A. Inglefield, and he was accompanied by Dr. Peter Sutherland, who had suggested such an exhumation while serving with Captain William Penny’s search expedition two years earlier. Inglefield’s Arctic exploits were considerable and, in 1853, he was awarded the Royal Geographical Society’s Arctic medal. During the award speech, Sir Roderick Murchison (head of the society) described the exhumation. The transcript of the speech reflects a number of errors and embellishments:

…Commander Inglefield, being in a private expedition, resolved to dig down into the frozen ground, for the purpose of ascertaining the condition in which the men had been interred. The opening out of one coffin quite realized the object he had in view, for at six feet [1.8 metres] beneath the surface, a depth reached only with great difficulty, by penetrating frozen ground as hard as a rock, a coffin, with the name of Wm. Heartwell, was found in as perfect order as if recently deposited in the churchyard of an English village. Every button and ornament had been neatly arranged, and what was most important, the body, perfectly preserved by the intense cold, exhibited no trace of scurvy, or other malignant disease, but was manifestly that of a person who had died of consumption, a malady to which it was further known that the deceased was prone.

Inglefield’s expedition was one of those supported by Lady Franklin. With a crew of seventeen on board the screw schooner Isabel, they were at Beechey Island on 7 September 1852. In his published journal, Inglefield described his first sight of the graves:

That sad emblem of mortality—the grave—soon met my eye, as we plunged along through the knee-deep snow which covered the island. The last resting place of three of Franklin’s people was closely examined; but nothing that had not hitherto been observed could we detect. My companion told me that a huge bear was seen continually sitting on one of the graves keeping a silent vigil over the dead.

Inglefield did not describe the exhumation of Hartnell in this journal, but there is a blank period in it covering the time between when he and Sutherland finished dining with the officers of the North Star and the departure of the Isabel from Beechey Island shortly after midnight “…with as beautiful a moon to light our path as ever shone on the favoured shores of our own native land.” An unpublished letter written by Inglefield to Rear-Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort on 14 September 1852, fills in this gap:

My doctor assisted me, and I have had my hand on the arm and face of poor Hartnell. He was decently clad in a cotton shirt, and though the dark night precluded our seeing, still our touch detected that a wasting illness was the cause of dissolution. It was a curious and solemn scene on the silent snow-covered sides of the famed Beechey Island, where the two of us stood at midnight. The pale moon looking down upon us as we silently worked with pickaxe and shovel at the hard-frozen tomb, each blow sending a spur of red sparks from the grave where rested the messmate of our lost countrymen. No trace but a piece of fearnought half down the coffin lid could we find. I carefully restored everything to its place and only brought away with me the plate that was nailed on the coffin lid and a scrap of the cloth with which the coffin was covered.

A remarkable letter and, as the 1984 research showed, accurate in its description of what had happened, even down to the removal of the piece of fabric. This was all the evidence that was needed to explain the history of the grave’s disturbance, the cause of the damage and the mystery of the missing plaque and fabric.

Another letter written by Inglefield on 14 September, this one to John Barrow Jr. at the Admiralty, differs from that to Beaufort, explaining that he had engaged not just Sutherland but six officers in the work, concealing the exhumation from his able seamen as he was wary of “the superstitions feelings of the sailors.” Most notably, where the letter to Beaufort professes detection of a “wasting illness” as Hartnell’s cause of death, Inglefield’s letter to Barrow is equivocal:

I was most anxious to have examined the body that the cause of death might be ascertained, but our utmost efforts had been exhausted and to lay bare the middle of it to take off the copper plate that was nailed on the lid and to discover that no relic had been laid with him that could give a clue to the fate of his fellows was all our strength and the intense cold that had set in with midnight permitted our doing.

Inglefield ends his letter to Barrow with a request for his discretion on the subject, “as the prejudices of some people would deem this intended work of charity sacrilege.” There can be no doubt, when their activities of that day are plotted out, that Inglefield would have been at the gravesite for only three or four hours prior to midnight, the appointed time for the Isabel to set sail, though he reported it was actually 1 AM when they got on board.

By this stage in the 1984 field season, there was no hope that the medical investigations of Hartnell and William Braine could be completed. It was obvious the scientific team would have to return to the Arctic island again to complete the research.

After photographs were taken of Hartnell, they began reconstructing the coffin and the gravesite. The lid was replaced on the coffin in the slightly askew position in which it had been discovered. A thin layer of gravel was lightly shovelled over the lid, and, in anticipation of their return to the site, a bright orange tarpaulin was placed over the gravel-covered coffin. Standing around the grave, shovels in hand, they remarked on how garish the fluorescent tarp looked in contrast to the grey surroundings of the quiet grave. “There will be no trouble in locating the coffin next year with that protecting it,” Kowal said.

Читать дальше