The coffin lid and box were then carefully wrapped in navy blue wool material, held in place by narrow white ribbons nailed to the coffin and outlining its contours. Torrington’s messmates had taken great care in preparing the labelled metal plaque that was to be attached to the outside of the coffin lid. Another task of the carpenters, under the direction of one of Terror’s lieutenants, was the preparation of an inscribed headboard.

Carrying picks and shovels, a small group of seamen from the Terror then walked from the ship to a location on the island just up-slope from the armourer’s forge. Here, they used their feet and shovels to sweep away a thin layer of snow from a small area of beach gravel. In the bitter cold, where the earth seemed like iron, they must have wondered about the seemingly backbreaking work they’d been assigned. But Franklin had ordered a proper burial, as close as circumstances would permit to that which John Torrington would have received in his native Manchester. After perhaps a few brief words, several of the seamen grabbed a pickaxe each.

The digging would have been treacherous and difficult, illuminated only by lamplight. In the near darkness, the pickaxes would have sent up showers of sparks as they struck against the icy earth. As the sailors took turns hacking at the ground in the deepening grave, they finally reached a depth of 5 feet (1.45 metres).

Preparations for the burial of John Torrington would have taken a day or two, but finally the small, slender coffin was lowered on ropes over the ship’s side down to the ice, several feet below. It was probably then secured to a small sledge and no doubt draped with a flag. A party of seamen picked up the ropes secured to the front of the sledge and began to drag it slowly over the ice and snow towards the gravesite. If Beattie’s own experience of King William Island was any indication, it must have been a tortuous trail, with small hummocks of ice preventing them from dragging the coffin in a straight line. Instead, they would have had to zigzag towards the shore.

A small procession would have followed, probably made up of Torrington’s messmates and friends from the Terror and led by Sir John Franklin, Captain Francis Crozier, Commander James Fitzjames and some of the Terror’s officers. Someone carried the wooden headboard, a monument not only to Torrington but, as events turned out, to the whole expedition.

A layer of snow found on the coffin lid by Beattie and his team shows that a light snow was falling that day, early in January 1846. The men who stayed on the ships probably watched as, man by man, the procession was swallowed by the snow. Soon all that would have been seen were the lamps, flickering and swaying like fireflies around the shadows of the invisible party. Then they too disappeared.

Franklin probably presided at the burial. He was a deeply religious man who, eight months earlier, had asked the British Admiralty to furnish one hundred Bibles, prayer books and testaments for sale at cost aboard the ships.

The snow, a spiralling yellow curtain in the lamplight, swirled around the group standing at the graveside. Some sifted and settled into the grave, obscuring the last view of Torrington’s coffin. Each breath of Franklin’s would have been made visible by the gripping cold, the sound of his voice blending with the icy, penetrating wind that always seems to blow at Beechey Island. His words were probably brief, but presented with obvious reverence and sincerity. Quickly, the ceremony was over, and thoughts turned away from the young man who, just months before at Woolwich, near London, had joined Franklin’s carefully selected crew a relatively healthy man.

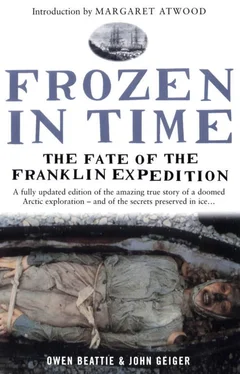

IN MANY WAYS, Torrington’s was an uneventful death, yet the confirmation of high lead levels in his body was of great significance in the context of the entire expedition. Beattie had stepped beyond the conventional theories about the expedition’s end. It now seemed clear that the startling proof of lead poisoning in Torrington, coupled with the results from the Booth Point skeleton and the bone remains gathered in 1982, demonstrated that lead had played an important, if not pivotal, role in the Franklin disaster. Lost was the accepted explanation of scurvy and starvation alone carrying off the expedition. Beattie’s medical findings from Torrington opened the door on a whole new way of looking at this and other nineteenth-century expeditions. But such a radical new theory about the underlying cause of the destruction of one of history’s great voyages of discovery needed to be backed up by as much evidence as possible. The more bodies demonstrating lead contamination, the more credible the case that the theory applied to the entire expedition.

Therefore, the laboratory discoveries made during 1984 only served to underline the importance of returning to Beechey Island and establishing the cause of death of Hartnell and Braine. Another important part of the investigation would be to establish what conditions must have been like on the expedition during 1845–46, and to reconstruct the last months and days in the lives of the three men buried on Beechey Island. Their bodies would provide an unprecedented and privileged opportunity to look into British and Canadian history—but a three-dimensional history, represented by the only true “survivors” of Franklin’s expedition.

After the 1984 field season ended and news of the preservation of John Torrington and John Hartnell was announced, two indirect descendants of Hartnell contacted Beattie. Donald Bray of Croydon, England, was astonished to see coverage of Beattie’s expedition and to hear the name of his ancestor mentioned. Bray, a retired sub-postmaster, had devoted years to tracing his family history and was in possession of rare letters and documents that added haunting insights into Hartnell’s family and life. Most touching were two letters to John and Thomas Hartnell, one sent by their mother, Sarah, and the other by their brother, Charles, both of which were intended to greet the sailors upon their completion of the Northwest Passage. The two men never received the letters, dated 23 December 1847. John Hartnell had already been dead for nearly two years and Thomas’s death probably came the following summer on King William Island.

“My Dear Children,” Sarah Hartnell’s letter began, “It is a great pleasure to me to have a chance to write you. I hope you are both well. I assure you I have many anxious moments about you but I endeavour to cast my prayers on Him who is too good to be unkind.” After a reference to her own illness and other news about family and friends, the letter ended: “If it is the Lord’s will may we be spared to meet on earth. If not God grant we may all meet around His throne to praise Him to all eternity.” Perhaps Sarah knew, as parents sometimes do, that her sons were facing their deaths.

Another descendant of John Hartnell would, along with three other specialists, join Beattie’s scientific team when he returned to the field in 1986. Brian Spenceley, a professor at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario, and a great-great-nephew of Hartnell, would soon be able to experience that which no other man has: to look into the eyes of a relative who has been dead for more than a century.

Jumping out of the Twin Otter onto the snow-blanketed ground of Beechey Island on 8 June 1986, Beattie was temporarily blinded by the bright, sunny sky and the sun’s rays reflecting off the white ground. Only gradually did major geographical features and the three tiny headstones that poked their way through the snow become visible, assuring him that he was once again on the island where so many memories lay.

This time Beattie planned to complete his examinations of the Franklin graveyard; part of his research team had already arrived with him from Resolute. That group, consisting of archaeologist Eric Damkjar, project photographer Brian Spenceley, historical consultant Dr. Jim Savelle (who was a co-investigator with Beattie during the 1981 season and now served as a research scholar at the Scott Polar Research Institute) and field assistants Arne Carlson, Walt Kowal and Joelee Nungaq would set up camp and then conduct the detailed archaeological work and exhumations. A team of specialists consisting of pathologist Dr. Roger Amy, radiologist Dr. Derek Notman, radiology technician Larry Anderson and Arctic clothing specialist Barbara Schweger would arrive one week later.

Читать дальше