Beattie was fascinated by the almost perfect preservation of the toes. The realization that a completely preserved human was attached to them had not yet sunk in. This was a strange period during their work: they were extremely close to a frozen sailor from 1846, and yet, they were concentrating so much on small details of thawing that the eventual exposure of the complete person was totally unexpected.

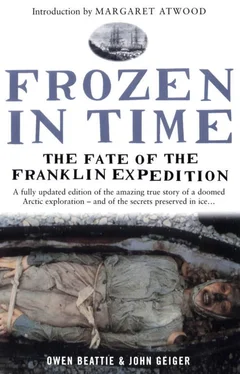

Arne Carlson was painstakingly thawing the section of coffin fabric covering the face area. Using a pair of large surgical tweezers, he pulled the material up carefully as it was freed by the melting ice. It was a difficult and meticulous task; as Carlson wanted to prevent any tearing of the material, he had to work hunched closely to it. Then suddenly, as he pulled gently upwards on the right edge of the material, the last curtain of ice gave way, freeing the material and revealing the face of Petty Officer John Torrington. Carlson gasped and sprang to his feet, allowing the fabric to fall back on Torrington’s face. Pointing with the tweezers, Carlson said in a strangely calm voice: “He’s there, he’s right there!” The others quickly gathered at the graveside, and, while everyone peered at the fabric covering, Beattie pulled it back.

All stood, numb and silent. Nothing could have prepared them for the face of John Torrington, framed and cradled in his ice-coffin. Despite all the intervening years, the young man’s life did not seem far away; in many ways it was as if Torrington had just died.

It was a shattering moment for Beattie, who felt an empathy for this man and a sadness for his passing—and as if he were standing at a precipice looking across a terrifying gulf into a very different world from our own. He was a witness to a tragedy, yet he had to remind himself that the tragedy belonged to another time.

The sky on the day of the autopsy was overcast, the grey clouds merging with the grey waters of Erebus Bay. The temperature was 30°F (-1°C), the wind a steady 12 miles per hour (20 km/h) from the south. Standing at the graveside and looking into the coffin, the gloom seemed to be reflected in Torrington’s simple grey linen trousers and his white shirt with closely spaced thin blue stripes. The shirt had a high collar and was pleated from the waist downwards, where it was tucked into the trousers. Under Torrington’s chin and over the top of his medium-brown hair was tied his kerchief, made of white cotton and covered in large blue polka dots.

The first photograph of John Torrington, taken moments after the wool coffin covering was pulled back.

John Torrington looked anything but grotesque. The expression on his thin face, with its pouting mouth and half-closed eyes gazing through delicate, light-brown eyelashes, was peaceful. His nose and forehead, in contrast to the natural skin colour of the rest of his face, were darkened by contact with the blue-wool coffin covering. This shadowed the face, accentuating the softness of its appearance. The tragedy of Torrington’s young death was as apparent to the researchers as it must have been to his shipmates 138 years before.

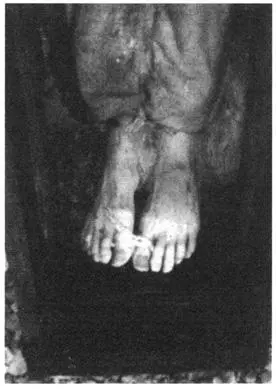

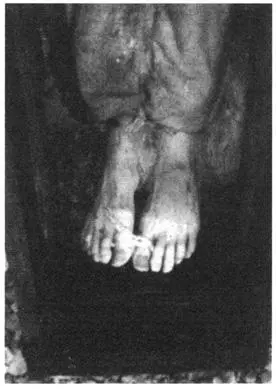

Torrington would have stood 5 feet 4 inches (163 cm) tall. His arms were straight, with the hands resting palm down on the fronts of his thighs, held in position by strips of cotton binding. These bindings were located at his elbows, hands, ankles and big toes. Their purpose was to hold the limbs together during the preparation of the body for burial. It was discovered later that his body lay on a bed of wood shavings, scattered along the bottom of the coffin, with his head supported by a thicker matting of shavings. He wore no shoes or boots, and there were no other personal belongings beyond his clothing.

Yet by far the strongest and most vivid memory Beattie has of this remarkable event centres not around the final thawing of Torrington’s body in the coffin, but on the lifting of the body out of the grave in preparation for autopsy. It was a remarkable and highly emotional experience, with Carlson holding and supporting Torrington’s legs, Beattie his shoulders and head. He was very light, weighing less than 88 pounds (40 kg), and as they moved him his head lolled onto Beattie’s left shoulder; Beattie looked directly into Torrington’s half-opened eyes, only a few inches from his own. There was no rigidity of his body, and rigor mortis would have disappeared within hours of his death. Although his arms and legs were tightly bound, he was completely limp, causing Beattie to comment, “It’s as if he’s just unconscious.”

OPPOSITE The dark stain on his forehead and nose marks where his face came into contact with the blue-wool coffin covering, which was folded inside the coffin lid.

ABOVE & BOTTOM John Torrington: The body was bound with strips of cotton to hold the limbs together during preparation for burial.

The two men carefully lowered Torrington to the ground outside the grave. There he lay, exposed to the Arctic sky for the first time in 138 years. If he had miraculously stirred to consciousness after his long sleep, Torrington would have thought that he had missed just two changes of season—a sleep of but eight months.

The bindings were removed and the body undressed. Away from the reality of the research project, an observer might suggest that the undressing of the body was an indignity to Torrington. But given the situation, both the need for medical evidence as to the fate of Franklin’s expedition and the team’s own feelings, which were very personal and intense, no indignity could exist.

Looking at Torrington lying naked on the autopsy tarpaulin, Beattie saw for the first time the condition of the young sailor and was shocked by the emaciated appearance of the body. All wondered aloud at what could have been the cause. Had he died of starvation? Was he suffering from some serious disease that had robbed him of his physical strength? It was immediately evident that foul play was unlikely; what they saw was a young man who had been extremely ill when he died. Of course, Torrington’s emaciated appearance was to a small extent due to the loss of moisture that occurs over a prolonged period of freezing, and in that sense, the preservation of the body could not be described as perfect. But every rib in the body was visible. And later, during the autopsy, no fat would be found, confirming that the weight loss before death was real and significant.

His hands, which Beattie commented “look like they are still warm,” were extremely long, delicate and smooth, “like you would expect a pianist’s to be.” There were no calluses on the palms or fingers, which would have been expected on an active participant in the expedition. Torrington had been the leading stoker on the Terror, and his hands would normally have shown evidence of his work if he had been recently active. Yet there was none, and for that reason Beattie was convinced he must have been too ill to work for some time before he died. Also, his nails were quite clean and he had recently been given a haircut, either in preparation for his burial or perhaps in the period just before his death.

Читать дальше