Work on clearing off the last layer of ice and gravel began almost immediately, and the source of the noxious odour soon became apparent. It was not partly decomposed tissue, as had been expected, but rather the rotting blue wool fabric that covered the coffin.

As they reached the coffin lid, the wind picked up dramatically and a massive black thunder cloud moved over the site. The walls of the tent covering the excavation began to snap loudly, and, as the weather continued to worsen, the five researchers finally stopped their work and looked at one another. The conditions had suddenly become so strange that Kowal observed, “This is like something out of a horror film.” Some of the crew were visibly nervous and Beattie decided to call a halt to work for the day. That night the wind howled continuously, rattling the sides of Beattie’s tent all night and sometimes smacking its folds against his face, making sleep difficult. Ruszala, unable to sleep, stayed in one of the long-house tents. All were concerned about the stability of the tent that had been erected over Torrington’s grave and, through the night, anxious heads would peer out of their tents to check on it. Towards morning, a violent gust slashed its way under the floorless tent, lifting it up and over the headboard before slamming it down on the adjacent beach ridge. Only a single rope held to its metal stake, preventing the tent from blowing into Erebus Bay. In the morning, the weather finally calmed and they dismantled the tent, remarkably only slightly damaged, and continued their excavation in the open.

Time was not a major consideration during the work, and, with continuous daylight, all soon lost track of the actual time of day. Eating when hungry, sleeping when tired, a natural rhythm developed, resulting in a work “day” stretching up to twenty-eight hours in length. The only reminders of the regimented, time-oriented outside world were the daily 7 AM and 7 PM radio schedules with the Polar Shelf operators. During these broadcasts they would pass along weather information and messages and listen to the messages and weather reported in turn from the other Polar Shelf-supported camps strewn across the Arctic.

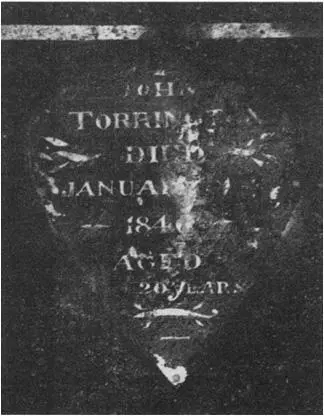

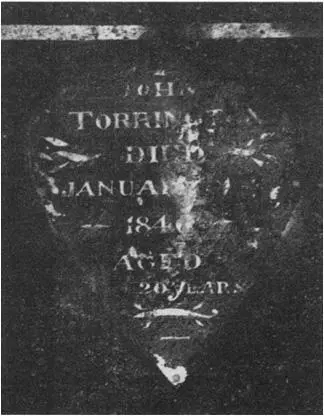

The tinned wrought iron plaque nailed to the lid of John Torrington’s coffin. The inscription reads: “John Torrington died January 1st 1846 aged 20 years.”

As the last layer of ice and gravel cemented to the top of the coffin was removed, Damkjar thought he could see something different in the texture of the fabric on the upper central portion of the lid. “Look at this,” he said, while continuing the thawing and cleaning. “It looks like something is attached to the lid or maybe carved into it.” Damkjar’s slow and meticulous work eventually revealed a beautiful hand-painted plaque that had been securely nailed to the coffin lid. Roughly heart-shaped, with short, pointed extensions along its top and bottom edges, it was made of tinned wrought iron, perhaps part of a tin can, and looked as though it was hand-cut. It was painted dark blue-green and on it in white was a hand-painted inscription: “JOHN TORRINGTON DIED JANUARY 1ST 1846 AGED 20 YEARS.”

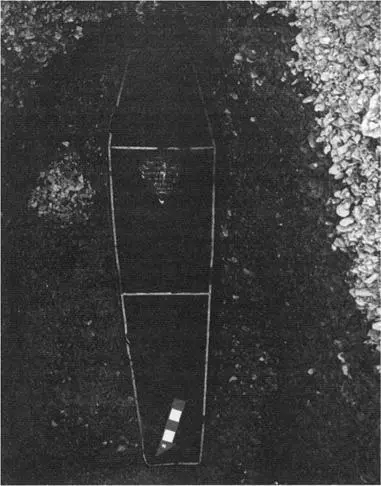

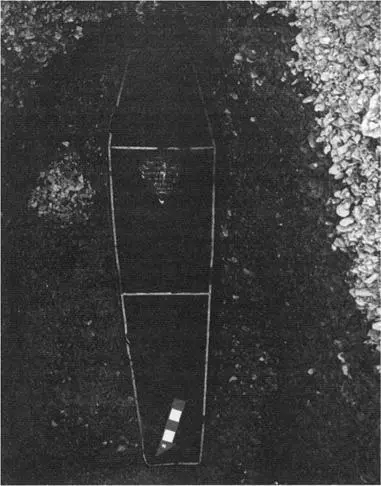

The coffin containing John Torrington. The arrow points to true north.

The plaque was a touching last gesture made by Torrington’s shipmates, and Damkjar spent a lot of time studying and sketching the discovery. Frozen for 138 years, the paint was showing signs of peeling, and rust had accumulated around its outer edges. The rust was carefully cleaned away and the plaque’s surface lightly brushed with water to remove the accumulated crust of silt.

The coffin itself was also impressive. It was obviously well made and its mahogany lid and box had been individually covered by wool fabric dyed dark blue. White linen tape had been tacked to the lid and box in a geometric, military, yet decorative manner that contrasted with the personal nature of the plaque. Bolted to the sides of the coffin were brass handles, the one on the right still in the “up” position, and bolted to the foot- and head-ends were brass rings. But what was most remarkable was the size of the coffin—it appeared almost too small to contain an adult, though this may have been an optical illusion created by the box being in a narrow hole.

During the hours spent removing the permafrost adhering to the coffin, the researchers would occasionally tap on the lid, expecting to hear a hollow sound each time, but this was never the case. Rather, it was like striking a large block of marble, a strange sound given the circumstances. This result obviously meant a heavy mass was enclosed. It couldn’t be just a body.

The removal of the lid was surprisingly difficult. It was very strongly secured to the box by a series of square shafted nails, and, as the researchers were soon to find out, it was “glued” down by ice within the coffin. The options for removing the lid were to pry it up, pull the nails or shear the nails at the junction of the lid with the box. Prying the lid would almost certainly destroy it: the wood was soft and delicate. For a similar reason, the team decided not to attempt to pull the nails out of the coffin. The best method, in Beattie’s mind, was to shear the nails. He placed the chisel edge of a rock hammer against the lid/box junction at each nail location and struck the rock hammer inward with another hammer. The chisel head drove into and through the nail without damage to the coffin.

Finally, after all the nails had been sheared and the ice holding down the lid had thawed, Beattie took the foot-end and slowly lifted it up, revealing the shadowy contents of the coffin. A partially transparent block of ice lay within, and, through the frozen bubbles, cracks and planes in the ice, something—some form—could be seen. But the more closely they looked, the more elusive the contents became.

This block of ice was the most serious obstacle yet. They had come to within inches of the body, only to be confronted with an apparently insurmountable obstacle. Work stopped while Beattie brooded over the next step. The options were few.

An aircraft engine preheater on the site, a noisy, temperamental and dangerous machine, could not be used to thaw the ice because hot air would put the biological matter and any artefacts enclosed at considerable risk. The outside air temperature was always at or slightly below freezing and in the grave lower still, so natural thawing was not a possibility. Chipping away the ice was not practical and probably impossible.

Ruszala suggested pouring water, some heated, some cold, onto the ice block. It worked better and faster than could have been hoped for. The researchers heated buckets of stream water on the camp stoves, lugged them bucket-brigade-style to the grave, then poured the water over the ice, from where it eventually ran out of the bottom join of the coffin onto the floor of the grave. The runoff was then scooped into a pail and dumped away from the gravesite. The team worked hard, spurred on by the knowledge that they would soon come face to face with a man from the Franklin expedition, and progress was swift.

The first part of Torrington to come into view was the front of his shirt, complete with mother-of-pearl buttons. Soon, his perfectly preserved toes gradually poked through the receding ice.

Most of the day was spent at this initial stage of exposure. All the while, the face remained shielded, covered by a fold of the same blue wool lain over the outside of the coffin. This created an eerie feeling among the researchers; it was almost as if Torrington was somehow aware of what was happening around him. But for artists’ portraits and a few primitive photographs, who living today has ever seen the face of a person from the earlier part of the Victorian era, a person who took part in one of history’s major expeditions of discovery? It would not be long before they were to gaze upon the face of this man from history.

Читать дальше