…on the side of the bay, opposite to Cape Riley, was an island; to which I… gave the name of BEECHEY ISLAND, out of respect to SIR WILLIAM BEECHEY.

Parry never set foot on the tiny island he named.

The northeast corner of Beechey Island slopes first gently upwards from the shore of Erebus Bay through a series of level beach ridges ideal for the construction of small buildings, or a graveyard. Upslope from the area used by Franklin and his crews, the land rises more steeply, culminating in high cliffs that overlook the campsite and the bay where the two ships would have been locked in the ice. The top of the island is remarkably flat, and in the southwest corner of the plateau, overlooking Barrow Strait, Franklin had the large rock cairn built. From this vantage point, 590 feet (180 metres) above sea level, it is possible to see Somerset Island 40 miles (70 km) to the south; Cornwallis Island is easily visible 30 miles (50 km) west across the entrance to Wellington Channel.

A small stream cuts down to the south of Franklin’s camp area, past the grey gravel covering the three graves, before emptying into Erebus Bay. Only in July and August does the stream come to life, providing a source of water for visitors to the site. In July, when the sun has warmed the rocky ground, hardy flowers bloom, filling the landscape with tiny random pockets of bright colour. But in August, as the team worked, the blooms had already fallen away.

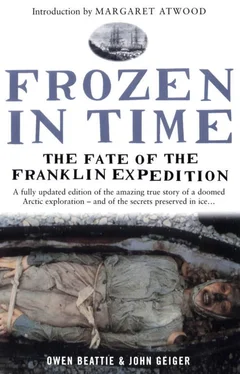

On 12 August 1984, having erected a tent shell over the grave to protect it from the elements, the University of Alberta researchers began to dig through the ground of Torrington’s grave. It took them less than an hour to remove the top layer of gravel using shovels and trowels, but when the excavation reached 4 inches (10 cm) into the ground, the men encountered cement-like permafrost. After a short, unsuccessful experiment in melting the permafrost with hot air, they resorted to pick and shovel to attack the frozen ground.

Soon after the uppermost levels of the permafrost had been chipped, broken and shovelled away, a strange smell was detected in the otherwise crisp, clean air. At first it wafted upwards intermittently, mingling with the smell from the smashing, sparking contact of pick with gravel, but as the excavation deepened the smell gained in strength and persistence and soon dominated the work. Although not totally the smell of decay, it served to remind Beattie of what he might encounter. But not until much later, when the coffin was fully exposed, would the true origin of the smell be determined.

Two long days were spent struggling through almost 5 feet (1.5 metres) of permafrost before the researchers got their first glimpse of the coffin. At the deepest part of the excavation, field assistant Walt Kowal, carefully clearing off a thin layer of snow at the foot-end of the grave, exposed a small area of clear ice. Beneath the ice casing he could see dark blue material. Until this discovery, there was speculation as to whether anyone was actually buried in the grave. Torrington’s body might have plunged through the ice into the freezing waters and been lost; other expeditions of the period had constructed dummy graves as a form of memorial. Or maybe the body would be simply missing, removed sometime during the past 138 years—a possibility that first occured to the exasperated team when they had dug about 1½ feet (.5 metre) below the top of the permafrost. As the researchers struggled deeper and deeper into the ground and still found no sign of a coffin, the thought that the grave really might be empty began to seriously trouble them. So when Kowal saw the blue material, he shouted, “That’s it! We’ve got it!” and stood back with a sense of accomplishment and relief.

Beattie and the others quickly gathered and knelt in a close circle around the discovery. With such a small area exposed it was impossible to determine what the fabric represented. Beattie thought it might be a section of the Union Jack. Others speculated it might be part of a uniform, a shroud or the coffin itself. But for a time the material was left under the thin cover of ice. Although the researchers had obviously discovered something in the grave and were anxious to continue, Beattie was still awaiting the exhumation and reburial permits from the government of the Northwest Territories, notification of permission from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and clearance from the chief medical officer. What had been done up to that point was considered archaeological work and was covered by a separate permit. Having established the exact location of the body, Beattie was now forced to call an end to the excavation until the required permissions arrived.

Abundantly clear to Beattie after removing more than 3 feet (1 metre) of permafrost, was that Torrington’s preservation would probably be excellent because of the ice. Originally there had been some doubt, as 138 Arctic springs and summers had passed. But even at the height of summer the season’s heat had had little or no effect on the upper reach of the permafrost—and Franklin’s men had gone to a good deal of trouble interring Torrington deep in the frozen ground. Then, as the researchers waited for the permits, they were confronted with a problem that could have ruined the whole project. Water began to flood the grave.

The water was subsurface run-off from the melting snow and permafrost of the slope and cliffs inland from the excavation, further fed by periods of rain and sleet. Everything was at stake. What had lain undisturbed for more than a century could be severely damaged or destroyed by water within hours if they didn’t act quickly.

It was decided that a shallow V-shaped ditch 130 feet (40 metres) long would be dug directly upslope of the graves (the three crewmen were buried alongside one another, with Torrington closest to the sea). This ditch, shovelled and scraped only a few inches into the permafrost, would act as a collecting canal, effectively diverting the water away from the graves. Within a matter of hours, the water seeping into Torrington’s grave had slowed to a trickle; eventually it stopped.

With still no news about the required permits, Roger Amy and Geraldine Ruszala made use of the down time to explore the spit of land connecting Beechey Island to Devon Island. Well into their hike, Amy, casting his eye along the spit, noticed a dirty-coloured snowbank about ⅛ of a mile (.2 km) away. His eyes were drawn by its unusual colour, but, as he looked more closely, he saw it move. Amy stopped dead in his tracks as the realization hit him: they were walking directly into the path of a polar bear. These huge and powerful animals, which can weigh 1,985 pounds (900 kg) and stand 11½ feet (3.5 metres) on their hind legs, often avoid human contact. However, periodic polar bear attacks do take place in the Canadian Arctic.

Amy whispered to Ruszala to start slowly backing up as the bear began sauntering towards them. They were at least ⅓ of a mile (.5 km) from camp, but they continued this cautious retreat almost the whole distance, with the bear following along at the same speed. Finally, with the camp within earshot, they turned and ran. “A bear, a bear,” Ruszala shouted, wildly pointing back towards the spit. The bear was still about one eighth of a mile away when Kowal and Damkjar fired several shots into the air to frighten the animal. These first blasts simply increased the bear’s curiosity, but the two men continued firing and, after ambling a few feet closer, the bear wisely decided it might be better—if not simply quieter—to alter its course and move on to other business. The crew followed the majestic animal’s retreat until it was last seen swimming speedily across Union Bay towards Cape Spencer. Amy and Ruszala, however, were badly shaken by the experience of being stalked.

Читать дальше