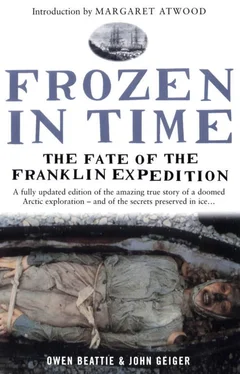

A cup made from an empty food tin from one of the Franklin search expeditions—showing that the cycle of lead contamination from the tins could continue even after they had served their primary purpose.

The problem with Beattie’s theory, however, was that skeletal remains alone were not enough to make a conclusive case. Although the lead values found so far were undeniably high, bone does not reflect recent exposure so much as it does lifetime exposure; lead sources present in the early industrial environment of mid-nineteenth-century England could have been to blame rather than any short-term exposure on the expedition. Also, contamination over the twenty-five or so years of the unknown Franklin crewman’s life could have caused physical or neurological symptoms, but they would have been much milder than those associated with classic lead poisoning and might have resulted in only slight behavioural problems. Therefore, to establish or disprove lead as a health problem on the expedition required the analysis of preserved soft tissue, which would reflect lead exposure following the departure of the expedition from England in May 1845.

The unexpected discovery of high lead levels shifted the focus away from the just-completed 1982 survey of King William Island. The gross examination of these bone materials, however, yielded two important observations: they added to the evidence for scurvy as a factor in the crewmen’s health late in the expedition and, significantly, backed up the bone lead findings. Values of the bone lead analyses from the remains of sailors collected in 1982 ranged from 87–223 micrograms per gram. By contrast, lead levels in bones of Inuit of the same time period and same geographical area ranged from 1–14 micrograms per gram. This provided convincing evidence that environmental lead contamination in the Arctic was not a contributing factor to the lead exposure. But even a physical anthropologist could learn little more from these test results. The definitive answer lay elsewhere: at the only known location where Franklin crewmen had died and been buried in the frozen ground by their shipmates. That place was tiny Beechey Island, off the southwest coast of Devon Island, where three sailors, Petty Officer John Torrington, Able Seaman John Hartnell and Private William Braine of the Royal Marines, died during the first winter of the Franklin expedition and were buried in the permanently frozen ground. What if those bodies remained frozen to this time? Wouldn’t they hold the key to whether Beattie’s lead theory was supportable or not?

Preserved human remains have given researchers and historians untold insights into life in very different worlds from our own. They are time capsules of the history and evolution of human beings. The mummified pharaohs of ancient Egypt, for example, have added greatly to our knowledge of that distant time, just as the bog people of northern Europe have shed new light on Iron Age man. But bodies have also remained frozen for great lengths of time. Examples include Charles Francis Hall, who died in 1871, and whose partially preserved remains were uncovered in Greenland’s permafrost in 1968. Prehistoric Inuit have also been found entombed, in the ice near Barrow, Alaska, and in Greenland, while in the Altai Mountains of southcentral Siberia, 2,200-year-old Scythian tombs have been discovered containing frozen and partially preserved human remains. The Arctic temperatures on Beechey Island were perfect for at least the chance of similar preservation.

Beattie first officially proposed the exhumation of the three graves to Canadian authorities early in 1983. In 1981 and 1982, he had required only an archaeology permit issued by the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre of the Northwest Territories and a science permit from the Science Advisory Board of the Northwest Territories to conduct his survey for skeletal remains on King William Island. The plan to investigate the buried corpses of Beechey Island, however, was far more complicated. The site was, in effect, a graveyard, and the identities of the three Franklin expedition sailors were known. Beattie had to ensure that all proper authorities were notified and that they approved of the planned research.

Archaeology and science permits were obtained from the Territorial government, which in turn asked that the British Admiralty, now part of the Ministry of Defence, be informed and that an attempt to contact any living descendants of the three sailors be made. The scientific team sought, and eventually received, clearance from the chief medical officer of the Northwest Territories, who assessed whether there was a potential health risk involved in the exposure of remains dating to the mid-nineteenth century. Exhumation and reburial permits, issued by the Department of Vital Statistics of the Northwest Territories, were also applied for. Permission from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police was also required, and, with its assistance, Beattie notified the British Ministry of Defence of the planned excavations. The Settlement Council of the Resolute Bay community also granted permission to conduct research on the site, which falls within their local jurisdiction. Finally, in an effort to contact any descendants of the three Franklin crewmen, Beattie wrote to the Times asking that a request for descendants to contact him be published as soon as possible. The short article produced no response.

Because of the nature of the work on Beechey Island and what might be contained in the graves, the research team was then expanded to include an archaeologist and a pathologist. At last, in August 1984, the team of scientists from the University of Alberta left Edmonton for Resolute, en route to Beechey Island. They shared the same hope: that the very cold that once worked to destroy the Franklin expedition would now help them unlock the mystery of its destruction.

Down in the hold, surrounded by the creaking of the wooden hull and the stale odours of men far too long enclosed, John Torrington lies dying. He must have known it; you can see it on his face. He turns towards Jane his tea-coloured look of puzzled reproach.

Who held his hand, who read to him, who brought him water? Who, if anyone, loved him? And what did they tell him about whatever it was that was killing him? Consumption, brain fever, Original Sin. All those Victorian reasons, which meant nothing and were the wrong ones. But they must have been comforting. If you are dying, you want to know why.

MARGARET ATWOOD, “The Age of Lead”

Mr Franklin smiled upon them all; he had a marble-white smile, like a tombstone angel, like a shot beluga whale on the beach; he slowly stretched the white rubber-marble skin of his face; as the lead-sugars and lead-garnishes of Mr Goldner worked themselves more thoroughly into his system, he came by degrees to bear more resemblance to another kind of whale, a grey one, gravel on its heavy skin…

WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN,

The Rifles

It is clear that all went exceedingly well for Sir John Franklin during the first months of his expedition. The Erebus and the Terror dodged through the ice of Baffin Bay in 1845 and quickly passed through Lancaster Sound, the eastern entrance to the Northwest Passage. Finding their westward progress impeded by a wall of ice in Barrow Strait, Franklin turned his ships north into the unexplored Wellington Channel for some 150 miles (240 km), penetrating to 77°N latitude. A second barrier of ice probably forced the expedition to retreat along the west and south coasts of Cornwallis Island (thus making clear that the land mass was an island) before finding a winter harbour at Beechey Island. Here, they settled into their first winter campsite, doubtless filled with a sense of purpose. They had not yet found a passage, but the coming summer held every hope of success.

Читать дальше