The bones were photographed, described, then collected, and the location marked on the team’s maps. Elated with their discovery and feeling renewed confidence that this area of the boat would yield new and important information, they continued on at an increased pace. When they saw the bright pink bundles of supplies in the distance, they broke into a jog and, if the packs had allowed, would probably have raced to their cache. Reaching the bundles almost simultaneously, they unslung their packs, rummaged quickly to locate their knives and within seconds were all slashing away at a claimed bundle. Each man searched for his favourite food: Kowal was looking for boxes of chocolate-covered macaroon candy bars; Tungilik, cans of roast beef; Beattie, tins of herring; and Carlson, canned tuna. With hardly a word to each other they dug into their food, sitting on the sandy beach ridge among the debris of their haphazard and comically frenzied search. The sounds of chewing, the crackle of plastic wrappers and the scraping of cans were interrupted by Kowal: “Can you believe us?” he said, looking up from a near-empty package, a chocolate macaroon poised in his right hand. “And we’re not even starving. Those poor guys must have really suffered.”

On 12 July the surveyors headed out from their newly established base camp. They found nothing more in the area where they had discovered the six bones, just two-thirds of a mile from their camp, but 2 miles (3 km) to the west of the camp they discovered a 100- by 130-foot (30- by 40-metre) area littered with wood fragments. As they closely searched the site, larger pieces of wood were also found. Schwatka’s description of the coastline and the small islands a few hundred feet out in Erebus Bay left the men with little doubt that they had reached the boat place where the large lifeboat from the Franklin expedition, filled with relics, was first discovered by M’Clintock and Hobson in 1859 and later visited by Schwatka in 1879. But the sight that had filled M’Clintock and the others with awe so many years before had vanished: the skeletons that once stood guard over their final resting place were nowhere to be seen. An exhaustive search of the site was conducted, and slowly, out of the gravel, came bits and pieces that graphically demonstrated to them the heavy toll of lives once claimed by the desolation of King William Island.

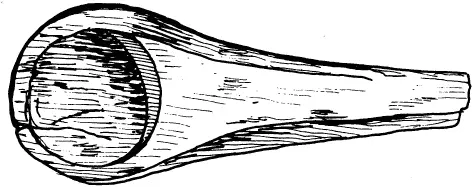

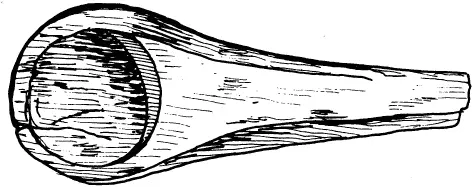

In the immediate vicinity, they eventually located many artefacts, including a barrel stave, a wood paddle handle, boot parts and a cherrywood pipe bowl and stem similar to those found by M’Clintock at the same site. More important, however, was the discovery of human skeletal remains. From the boat place and scattered along the coast to the north, they found bones from the shoulder (scapulas) and leg (femurs, tibias). Several of the bones showed scarring due to scurvy—similar to the markings discovered on the bones found a year earlier near Booth Point. (In total, evidence of scurvy would be found in the bones of three individuals collected in 1982.) The team worked long and hard, each of the four men combing the ground for any relic or human bone. Dusk soon surrounded them, but no nightfall follows dusk during the summer at such high latitudes. It was under the midnight sun that Tungilik made the survey’s most important find.

Cherrywood pipe.

While systematically searching the boat place, Tungilik caught sight of a small ivory-white object projecting slightly from a mat of vegetation. Picking at the object with his finger, out popped a human talus (ankle bone). With his trowel, Carlson scraped the delicate, dark green vegetation aside, revealing a series of bones immediately recognizable as a virtually complete human foot. Continuing his excavation, which lasted into the early morning hours of 13 July, Carlson found that most of the thirteen bones from the left foot were articulated, or still in place, meaning that the foot had come to rest at this spot and had not been disturbed since 1848. The remaining skeletal remains varied from a calcaneus, or heel bone (measuring 3 inches/8 cm in length), to a tiny sesamoid bone (no bigger than .12 inches/3 mm across). Also found was part of the right foot from the same person, which supported the interpretation that a whole body once rested on the surface at this spot.

M’Clintock had argued that, as the lifeboat was found pointing directly at the next northerly point of land, it was being pulled back towards the deserted ships, possibly for more supplies:

I was astonished to find that the sledge (on which the boat was mounted) was directed to the N.E… A little reflection led me to satisfy my own mind at least that this boat was returning to the ships. In no other way can I account for two men having been left in her, than by supposing the party were unable to drag the boat further, and that these two men, not being able to keep pace with their shipmates, were therefore left by them supplied with such provisions as could be spared, to last them until the return of the others with fresh stock.

The 1982 discoveries at the boat place supported this interpretation: the human skeletal remains were found scattered in the immediate vicinity of the lifeboat, and in the direction of the ships for a distance of two-thirds of a mile. It appears that those pulling the lifeboat could go no further and had abandoned their burden and the two sickest men. They continued on, but some had nevertheless died soon after.

In all, the remains of between six and fourteen individuals were located in the area of the boat place. In determining the minimum number of individuals from the collection of bones, Beattie first looked to see how many of the bones were duplicated. Then he examined their anatomy, such as size and muscle attachment markings, comparing bones from the left and right sides of the body to see if they were from one or more individuals.

Beattie was sure that the bones had been missed by Schwatka. From his journal, it is obvious that Schwatka was reasonably thorough in his collection of bones. He had discovered the skull and long bones of at least four individuals and buried these at the site. As in the previous searches along the coast that summer, Beattie and his crew were not able to find this grave. Of the bones discovered by the scientists in 1982, no skull bones were found.

Strangely, the most touching discovery made at the boat place was not a bone but an artefact, found by Kowal. Surveying a beach ridge further inland on 13 July, he saw, lying among a cluster of lemming holes, a dark brown object that, on closer inspection, turned out to be the complete sole of a boot. Picking it up he could see that three large screws had been driven through the sole from the inside out, and that the screw ends on the sole bottom had been sheared off. Kowal carried the artefact back to camp, where the others, who had been cataloguing the collection, examined it. It was obvious that the screws were makeshift cleats that would have given the wearer a grip on ice and snow—a grip absolutely necessary when hauling a sledge over ice.

It was this object, more than even the bleached bones of the sailors, which brought home to the four searchers the discomfort, agony and despair that the Franklin crews must have endured at this final stage of the disaster. For the research team, the piece of boot symbolized the final trek of the men of the Erebus and Terror. The imagination can play tricks in such situations. And while sitting alone during the dusk-shrouded early hours of 14 July, with brisk winds blowing in off Victoria Strait, Beattie felt that Franklin’s men did indeed still watch over the place. It was as if the dead crewmen might yet rise up for one last desperate struggle to ascend the Back River to safety.

Читать дальше