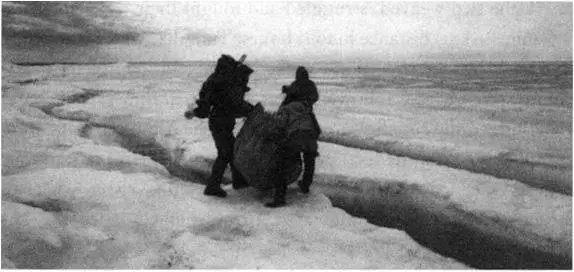

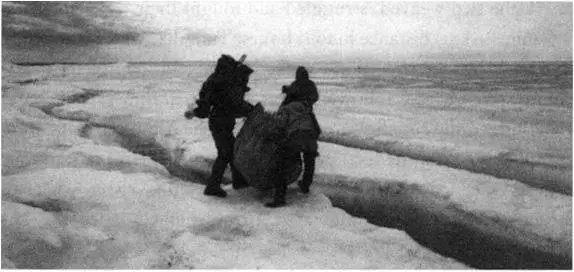

While Beattie and Carlson mapped and collected the few artefacts found at Crozier’s Landing, Kowal and Tungilik built a makeshift sledge from scraps of lumber found beside the ice edge. Round nails and the relatively fresh appearance of the wood suggested it was of very recent origin, and the two carpenters, using rocks for hammers, put it to good use. They planned to haul the camp supplies, mounted on the sledge, south across ice-covered Collinson Inlet to near Gore Point. Although the ice was fairly rotten and beginning to break, they calculated that, with some care, they could save more than a week’s walking by cutting across the inlet’s mouth instead of going round its wet and marshy source.

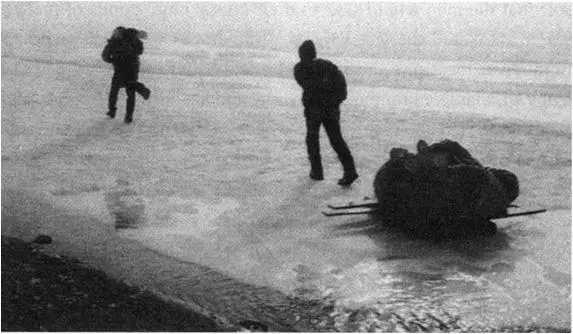

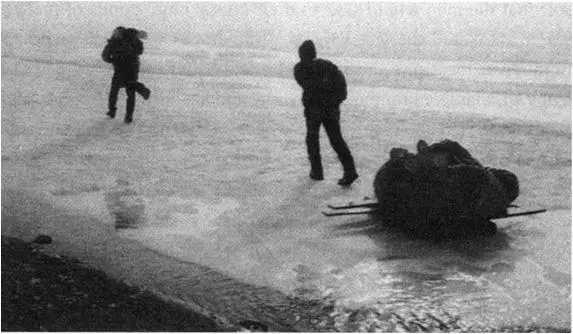

ABOVE Carrying survey supplies out onto the ice of Victoria Strait and BELOW over Collinson Inlet, this time using a sledge made from twentieth-century timber and nails found at Crozier’s Landing.

Within an hour the sledge was complete and they prepared to resume their southward trek. The early evening hours were becoming cool and a silvery fog hung over the ice. The wind, usually a constant companion, had dropped to a whisper. Beattie and Carlson, who stayed behind to complete the artefact collection, watched as the other two were soon engulfed by the swirling fog. They stood silently for a few moments, listening to the receding sounds of trudging footsteps and the rasp of the sledge runners.

With Kowal pulling the sledge by a rope looped around his chest, the two weaved, struggled and fought their way across the 2½-mile (4-km) distance in four hours. Tungilik, with his superior knowledge of ice conditions, walked ahead and scouted the safest route, which Kowal followed faithfully. When they reached land they lugged the supplies up onto the beach. Although both were completely exhausted, they immediately began the arduous journey back to rendezvous with Beattie and Carlson, who had struck out across the inlet after their artefact collection was completed.

The ice was very difficult and dangerous to cross. Parts were so soft that the men would sink to their knees; large ponds of melted water blanketed the ice surface. Wide cracks were a hazard in a number of locations and innumerable smaller cracks braided the ice. Tall, massive hummocks of snow and ice dotted the route, and Beattie worried about surprising a bear hidden on the opposite side of one of these—a healthy paranoia that resulted in a wide berth being given to these small ice mountains. As well, he noted that the ice they travelled over, and had seen offshore since their arrival on King William Island, was first-year ice, often little more than 12 inches (30 cm) thick. Recently, he knew, Polar Continental Shelf Project scientists had used ice core samples taken from High Arctic ice caps to study climate conditions over time, and had concluded that the Franklin era was climatically one of the least favourable periods in 700 years. This explained the multiyear ice encountered by Franklin off the northwest coast of King William Island, ice that was sometimes more than 80 inches (200 cm) thick.

Carrying packs filled with artefacts, Beattie and Carlson laboured across the ice for an hour. The fog had finally lifted when they saw Kowal and Tungilik a mile distant, heading towards them. Within another hour they were all safely across.

On 4 July, the team searched unsuccessfully for the grave of a Franklin crewman recorded by Schwatka. They also searched for the cairn at Gore Point, where a second Franklin expedition note was discovered by Hobson in 1859. (Virtually identical to the note found at Crozier’s Landing, this scrap of paper contained only information on the 1847 survey party of Gore and De Vouex. There were no marginal notes on the document, though, curiously, the error in the dates for wintering at Beechey Island was repeated.) A small pile of stones was located on the far end of Gore Point. As the pile was definitely of human origin and did not come from an old tenting structure (either Inuit or European), it seemed likely that the stones represented the dismantled cairn that had once held the note.

Moving southward along the coastline, the team encountered nothing to indicate that the area had been visited recently, only locations marking the probable campsites of Schwatka and his group. The next focal point in their survey was the supply cache that had been dropped from the air on the south shore of Seal Bay. After spending two days at this location, making good use of the stores of food and observing the dozens of seals that dotted the ice floes offshore, the team surveyed the coast down to a location adjacent to Point Le Vesconte, where Schwatka discovered and buried a human skeleton. Point Le Vesconte is a long, thin projection of land that is actually a series of islets. At low tide it is easy to walk out along the point, but, as the team discovered, at high tide the depth of water separating the islets can nearly reach the waist.

Of all of Schwatka’s descriptions, the locations of two skeletons along this coast were the best documented and most accurately identified on the survey team’s maps. At Point Le Vesconte, Schwatka had recorded human bones, including skull fragments scattered around a shallow grave that contained fine quality navy-blue cloth and gilt buttons. The incomplete skeleton, of what Schwatka believed had been an officer, had been carefully gathered together and reburied in its old grave and a stone monument constructed to mark the spot. Yet again, the survey team failed to locate this grave or the second one on the adjacent coastline. Beattie was disappointed. In “curating” the skeletal remains he discovered, Schwatka had apparently marked each grave with “monuments” consisting of just a couple of stones. Along King William Island’s gravel- and rock-covered coastline, such graves were lost in the landscape. After scouring the area for an entire day, the frustrated party pushed on to the south.

On the morning of 9 July, Beattie turned on his shortwave radio for the daily 7 AM radio contact with Resolute. But instead of being greeted by the reassuring and familiar voice from the Polar Shelf base camp, only a vacant hissing sound was heard. No contact with Resolute could be made that morning. The aerial was checked, the batteries changed, the radio connections and battery compartment cleaned, all in preparation for the regular evening communication.

Loss of radio contact is serious in the field; within forty-eight hours the Polar Shelf will dispatch a plane to the last known location of the party, bringing an extra radio and batteries. There may be a genuine emergency, but if the reason for missing radio contact is trivial, such as simply sleeping through the schedule, the Polar Shelf will put in a bill for the air time spent on re-establishing contact, for an important function of the twice-daily radio contact is to track the status of each group of scientists working in the field throughout Canada’s Arctic. It is to everyone’s advantage to pass along position information and plans for camp moves to the officials in Resolute.

With their radio not functioning, the team was completely cut off from the outside world. As the group sat around discussing the consequences, they guessed it must be a radio blackout caused by solar activity—a relatively common occurrence. What worried Beattie was that, in their last radio contact with Resolute, they had indicated they were on their way to a predetermined camp location, 25 miles (40 km) south at Erebus Bay. Loss of contact with Resolute meant there was a possibility that a plane would be sent out within the next day or two to Erebus Bay. There was some urgency, therefore, to get to that location before the plane. Three thoroughly exhausting, long days of surveying and backpacking followed before radio contact was at last resumed; for those days, they felt like they were the only people on earth. The absolute isolation imposed by the radio blackout was a sobering experience, one they were not anxious to repeat.

Читать дальше