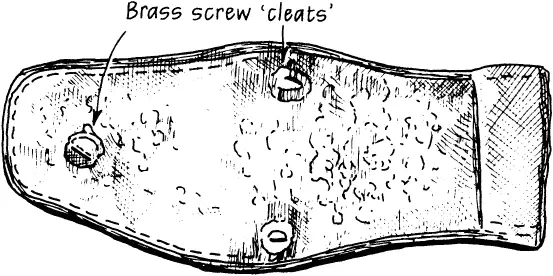

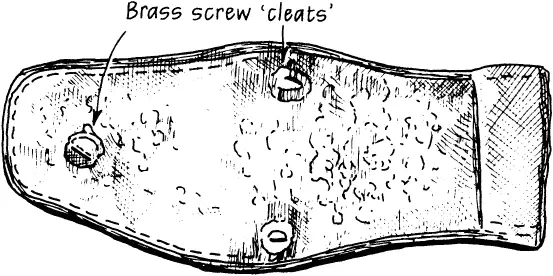

Boot sole found at the “boat place,” showing screw “cleats.”

Later, Beattie, Carlson, Kowal and Tungilik surveyed 3 miles (5 km) further to near Little Point. To the west of this location was a long inlet filled with rotten ice, which effectively formed a barrier to any further survey that season. And so, packing their precious cargo of bones and artefacts, the team readied to leave the island. With the King William Island surveys at an end, Beattie was already wondering what new insights into the Franklin disaster his small collection of bones would provide.

During the early months of 1982, bone samples collected from four skeletons discovered on King William Island in 1981—three Inuit (two males, one female) and the Franklin expedition crewman from near Booth Point—were submitted to the Alberta Soil and Feed Testing Laboratory for trace element analysis. The reason for the testing was to gain possible insights into the individuals’ health and diet. The method of analysis used, called inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy, would assess the level of a number of different elements contained in the bones. At the time, Owen Beattie believed that scurvy and starvation were the likely cause of the Franklin disaster, but the 1981 bone samples were submitted without instructions to look for a particular element.

By the time Beattie returned from the field in 1982, the findings of the trace element analysis were waiting for him. The results showed that the level of lead found in the Franklin expedition crewman’s bones was extremely high, raising the possibility that some—or all—of the crew had been exposed to potentially toxic levels of lead; and that the difference between the lead levels found in the Inuit skeletons and that of the Franklin crewman was astounding. In the three Inuit skeletons, the lead levels ranged from 22 to 36 parts per million. (Such levels fall within the range identified in other human skeletons from cultures with no exposure to lead beyond that found in the environmental background.) In contrast to the Inuit skeletons, the occipital bone from the Franklin crewman registered levels of 228 parts per million. These results meant that if the Franklin crews had suffered this level of intake during the course of their expedition, it would have caused lead poisoning—the effects of which in humans have been well documented and include a number of physical and neurological problems that can occur separately or in any combination, depending on the individual and the amount absorbed. Anorexia, weakness and fatigue, irritability, stupor, paranoia, abdominal pain and anaemia are just a few of the possible effects.

Lead poisoning had plagued the ancient Greeks and Romans, who employed kettles, buckets, pipes and domestic utensils made of lead. Because the metal has a saccharine taste when dissolved (which is why the acetate is commonly called “sugar of lead”), the Romans had even used sheet lead to neutralize the acidity of bad wine. Even in 1786, when Benjamin Franklin provided the first detailed medical description of the “mischievous effect from lead,” the serious, even deadly, risks that he enumerated were nonetheless not widely disseminated. Cosmetics such as face pomades and hair powder, pewter drinking vessels, tea caddies, water pipes and cisterns, children’s toys and candlewicks all caused lead poisoning in the nineteenth century.

One scholar who has studied the circumstances under which lead poisoning arises, describes the outbreaks as “legion, oftentimes bizarre, and sometimes dramatic.” A mystery illness, for instance, called the “York Factory Complaint,” afflicted the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fur trade post from 1833–36. Most of the men at the fort suffered the telltale signs of “debility,” resulting in a series of unexplained deaths. Symptoms included “a total loss of reason,” “great nervous weakness,” weight loss, convulsions and stupor. One new arrival at York Factory in 1834 described the inhabitants as having a peculiar pallor, which made them seem “more like ghosts than men.” At the time, the illness was blamed on a number of factors, including “the want of vegetables and fresh beef.” Today, scientists attribute the outbreak to saturnism (lead poisoning), most likely derived from the lead-lined containers used for food or drink.

Whilst lead’s dangers were little understood at the time, some warnings did enter the medical and scientific literature of the mid-1800s—an article in Scientific American that appeared in 1857, for instance, declared “all combinations of lead are decidedly poisonous.” One particular characteristic militated against its discovery, and gave rise to lead poisoning’s other name: the “aping disease.” As one scientific study concluded: “So protean are its manifestations that it, like syphilis, may simulate a hundred other conditions.” Lead poisoning also has a way of appearing in epidemics, so that it was often attributed to some unrelated cause. In the context of Arctic expeditions, these symptoms—emaciation, discolouration of the gums, abdominal colic, shooting pains of the limbs—would naturally suggest to medical officers and expedition commanders a well-known and feared illness: scurvy. All are, however, symptoms of lead poisoning.

Most poignantly for those dragging heavily laden sledges, “lead poisoning has a mean way of penalizing the extremity most used in muscular effort.”

The unexpected discovery of elevated bone lead levels begged another question: What could have been the source? Suspicion immediately fell on the relatively new technology of preserving foods in tin containers, as used by the Franklin expedition. Nearly 8,000 lead-soldered tins containing 33,289 pounds (15,113 kg) of preserved meat were supplied to the expedition, as well as the tinned equivalent of 2,560 gallons (11,638 litres) of soup, 1,200 pounds (545 kg) of tinned pemmican and 8,900 pounds (4,040 kg) of tinned preserved vegetables. (Even today, the seams and seals of some tins are known to be a significant source of lead contamination in some developing countries, so this certainly could have been a problem.) But ignorance of its ill effects remained commonplace. Just as authorities had failed to understand the link between scurvy and reliance on tinned food, so too they failed to understand the effect of interior-lead-soldered seams on tinned foods, and thus, on those dependent for long periods on such provisions. In addition, lead-glazed pottery and tableware were used by nineteenth-century British Arctic expeditions. The storage and serving of acidic foods and beverages (which can dissolve lead salts)—such as lemon juice, wine, vinegar or pickles—in lead-glazed vessels could have been a major source of lead ingestion during the expedition. Other possible sources of lead on the expedition included tea, chocolate and other foods stored in containers lined with lead foil. In addition, food colouring, tobacco products, pewterware and even lead-wicked candles could have added to the possible contamination. As a result, lead poisoning, compounded by the severe effects of scurvy, could have been lethal for many members of the expedition’s crews during the early months of 1848. Rapidly declining health might well in fact have been the major reason for the decision by Crozier and Fitzjames to desert the ships. As the note discovered by Hobson on King William Island shows, nine officers and fifteen men had already died by 25 April 1848.

This radical new theory, proposed by Beattie, would prompt debate among historians who had, for so long, relied on the theories of nineteenth-century searchers and, later, parliamentary inquiries in Britain as the basis for their investigations. While such sources are invaluable in the reconstruction of events, all the volumes written about the doomed expedition combined were not able to provide the scientific data Beattie had already gained from the scanty physical remains found on King William Island.

Читать дальше