For the next two hours they walked, waded and jumped over fractures and cracks in the ice and areas of open water created by the stream, until they were able to angle back to the safety of the shore on the far side of the stream. After kicking off their boots and taking a well-earned rest, the survey then continued south along the shoreline to the place visited by James Clark Ross in 1830, subsequently named Victory Point.

Standing on the low rise of the point and looking south, Beattie was astonished by the accuracy of the scene, as depicted in an engraving made from a sketch drawn by Ross during his explorations—part of his uncle Captain John Ross’s failed 1829–33 expedition. James Clark Ross described his visit:

On Victory point we erected a cairn of stones six feet high, and we enclosed in it a canister containing a brief account of the proceedings of the expedition since its departure from England… though I must say that we did not entertain the most remote hope that our little history would ever meet an European’s eye.

Despite the accuracy of the engraving, nothing could be found of the cairn erected by Ross. Only a small cairn dating from the mid-1970s remained.

Victory Point is a low gravel projection into Victoria Strait, rising less than 33 feet (10 metres) above the high-water mark. From this spot it is possible to see Cape Jane Franklin several miles to the south, glazed with a permanent snow cover on its western rise, and to the west, the thin, horizontal dark line of Franklin Point. Ross named these features in 1830, in the case of Franklin Point writing in his journal that “if that be a name which has now been conferred on more places than one, these honours… are beyond all thought less than the merits of that officer deserve.” (In one of those instances of tragic irony, Sir John Franklin would die within sight of Franklin Point and Cape Jane Franklin, seventeen years later.)

Two miles (3 km) south of Victory Point, Beattie and his small party came across another, much smaller, projection of land, marking the site where the crews of the Erebus and Terror congregated on 25 April 1848, three days after deserting the ships 15 miles (24 km) to the NNW. It is this place that, along with Beechey Island, forms the focal point for the discovery of the fate of the expedition, for a note of immeasurable importance was left here, providing some of the few concrete details relating to the state and action of the crews from the wintering at Beechey Island in 1845–46 to the desertion of the ships on 22 April 1848.

Setting up camp, Beattie prepared to spend two days thoroughly researching and mapping the site as well as surveying the surrounding area. The two tents were placed so that their doorways faced each other; the team could then sit and prepare meals and talk in their own makeshift courtyard. During that first evening, the sky and clouds to the south darkened to a deep purple and bolts of lightning flashed out from the clouds, reaching down towards the ground. Although orange sunlight still shone on their camp, the four watched with anxiety as the dark storm moved westward to the south of them. The site, known as Crozier’s Landing, was so flat that their metal tent poles were prominent features—perhaps even lightning rods. They were relieved when the storm at last faded from view.

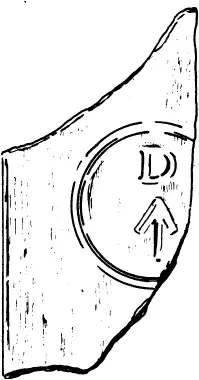

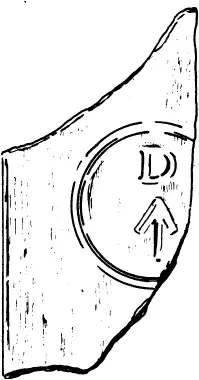

By 1982, few relics of the Franklin expedition remained at Crozier’s Landing. Where piles of the crews’ discarded belongings once lay strewn about, only scattered boot and clothing parts, wood fragments, canvas pieces, earthenware container fragments and other artefacts could now be gleaned from among the rocks and gravel. One rusted but complete iron belt buckle was found during the survey, as was a stove lid, near the spot where M’Clintock had located a stove and pile of coal from the expedition. A smashed but complete amber-coloured medicine bottle was also found, as was part of the body of a clear glass bottle, complete with navy broadarrow marking.

Glass fragment showing the navy broadarrow.

What struck Beattie was the paucity of the remains marking this major archaeological site. How could a place with such a history of tragedy and despair—shared by 105 doomed souls—appear so impartial to the events that transpired here during late April 1848? The artefacts that were mapped and collected in 1982 were pathetic, insignificant reminders of the failed expedition. Disturbances at the site were such that a search for the grave of Lieutenant John Irving, discovered by Schwatka, failed to turn up anything, though a series of at least thirteen stone circles indicated the actual location of the tenting site established by Franklin’s men. Other tent circles attested to the visits by searchers, primarily M’Clintock and Hobson in 1859 and Schwatka in 1879, and by Inuit. Evidence of more recent visits were also clearly visible: a hole excavated by L.T. Burwash in 1930, small piles of corroded metal fragments (possibly the remains of tin canisters), a note left by a group during an aerial visit made in August 1954 and other signs of visits made within the last decade. A modern cairn is situated at the highest point of the site, representing the approximate location of the cairn in which the note was discovered by Hobson in 1859.

However, Beattie’s group did make one interesting discovery as they marked with red survey tape the locations of artefacts scattered along the beach ridge. Paralleling this ridge, and towards the ice offshore, was an area of mud that, because of the time of year, had begun to thaw—and visible in the mud were coils of rope of various sizes. The anaerobic conditions of the mud and the long period of freezing each year had resulted in good preservation of the organic material, in stark contrast to the disintegrated rope and canvas fragments found on the gravel surface. One of the preserved coils was of a very heavy rope, about 2 inches (5 cm) in diameter. Yet despite this discovery, so little of the presence of Franklin’s men at Crozier’s Landing remained that it was almost impossible to visualize that scene of bustling activity and preparation that would have been played out in growing despair. The last marks of this most famous of Arctic expeditions were all but erased, as if scoured away by the constant, turbulent and chilling winds that blow off the ice. Beattie began to entertain the possibility that pursuing new leads into the fate of the expedition on King William Island might be a waste of time.

From the perspective gained at Crozier’s Landing, where the final agony of the explorers began in 1848, perhaps the deeper mystery was not so much the fate of the 105 men who died trying to walk out of the Arctic (which had until this time been Beattie’s focus), but the mystery of the twenty-four others who died (including a disproportionate number of officers) while the expedition was still aboard-ship and food stores remained. (After deserting their ships, the deaths of the 105 survivors seemed unavoidable along the desolate shores of King William Island.) To Beattie, it became increasingly obvious that the real Franklin mystery lay not here at its tragic end, but much earlier: the period from August 1845, when the expedition sailed into the Arctic archipelago, until 22 April 1848, when the ice-locked vessels were deserted off King William Island. For it was during those thirty-two lost months that nine officers, including Sir John Franklin, and fifteen seamen died. (Three were buried at Beechey Island; the graves of the others have never been found.)

Even before the ships were deserted, the Franklin expedition had been an unprecedented disaster. Its heavy losses contrasted sharply with the escape of John Ross and his crew, including James Clark Ross, after they deserted the discovery ship Victory on the southeast shore of the Boothia Peninsula in the early 1830s. For despite all that time in the Arctic, away from the protection of their ship and suffering the ravages of scurvy, Ross returned to England with nineteen of his twenty-two men. To Beattie, it began to appear that the most important insights into the Franklin disaster would come from the group of twenty-four who died aboard ship.

Читать дальше