Soon, however, the papers began to add their own thundering editorials to the narrative. On Monday, 15 November, The Argus editorial declared:

We must again advert to the evils arising from the sending out of large numbers of passengers in single ships. We lately alluded to several cases in which the mortality during the voyage had arrived at a very frightful extent. Since then, large English vessels have arrived also furnishing a sad list of deaths. Several vessels are now in quarantine, among them the Ticonderoga , which recently arrived with the terrible loss of 104 lives. When she anchored in our port, many scores of passengers were still ill, the doctor and his assistant were both laid up, and the medical stores were all consumed. From the result of such experience, it seems improper that any ship however large, however splendid her accommodation should endeavour to bring many hundred passengers for so long a voyage. Those vessels which have conveyed 200 or 300 passengers each have usually arrived without any serious loss of life; but those conveying 600 or 700 and upwards have frequently furnished such a list of casualties, as to lead us to strongly recommend to ship-owners to abstain from sending them, and passengers to avoid coming by them.

Word of the plague ship began to spread beyond the borders of the new colony, and soon a blistering article appeared in the combative but influential fortnightly Australian and New Zealand Gazette. In it, not only were the foretold consequences of employing large vessels laid bare, but the very practices of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission, as well as assisted emigration in general, were brought into question:

In our last number we alluded to the fearful mortality which had taken place on board some ships from Liverpool to Australia, in consequence of over-crowding. Liverpool, or, rather, American ships, sailing from that port to the United States, have established an unenviable reputation for this system of packing live cargo, as Irish emigrants to America are evidently considered. Our impression was, that in Australian emigration a different course had been pursued by Liverpool shipowners with regard to Australian ships. And on inquiry we find that it is so; private ships sailing from Liverpool being in quite as good condition, both as regards comforts and provisions, as any out of London.

Our readers will be surprised that the floating pest-houses, in which two hundred and seventy-nine souls have been lost to their families and the colonies, are the property of, for the time being, and were shipped out under the eye of her Majesty’s Emigration Commissioners, who have thus wasted the above enormous quantity of human life, and with it upwards of £5000 of the Victoria colonists’ money. In the name of humanity, we trust the colonists will, as they have intimated, stop the remission of any further land funds, if this is to be the use made of it. But let us recount the mortality on board these sea-shambles Borneuf , 83 dead; Wanata , 39 dead; Marco Polo , 53 dead; and Ticonderoga , a hundred and four dead! Total, 279 persons, starting from England less than six months ago, full of life and spirits at the cheering prospects before them. These have been hurried into eternity from having put confidence in her Majesty’s Emigration Commissioners, whose latest discovery it appears to have been that the best way of promoting the health and safety of 800 souls on board each ship was to stow them away in the space which private shipowners would have allotted to 700. But on this point we will let Mr Rankin, the chairman of the Liverpool Shipowners’ Association, speak—The doctor is dead, and almost all the survivors are down with fever. The last case is the most striking, because the voyage, of 68 days only, must have been performed with winds invariably favourable. What, then, was the cause of this unusual and frightful mortality? The system of packing, which sends 800 in a space not more than enough for 700, and which stows passengers in lower deck berths without any better means of ventilation than a canvas windsail, which cannot be used in storms, when most needed.

As Chairman of the Liverpool Shipowners’ Association, I deem it my duty to state that not one of the above vessels was sent out by private individuals, but all of them were taken up and sent out by the Commissioners of Emigration. Every emigration ship is inspected by the Government officer, and no more passengers are allowed than the act of Parliament authorizes. So that private ships are compelled to take no more passengers than they can carry in health and safety. But her Majesty’s Emigration Commissioners have the power of experimentalizing as to how many out of eight hundred souls can be safely landed from one ship.

Our wonder is that they did not go the full length of the experiment, and stow away the whole of the live lumber in casks, with holes bored at the bottom. But happily, amidst this horrible slaughter, the weather was fine and the winds favourable, or few indeed would have reached their destination. In March last year, the Liverpool Shipowners’ Association urged on the Government the fact that no ship, whatever might be her size, could carry more than 600 persons in safety. The Great Britain , the largest ship afloat, took out this number, and lost one. In the very teeth of the Liverpool Shipowners’ Association, and in their own port, the emigration commissioners put on board 800, though the ships were not of the largest size! Had one of these ships only been thus fearfully visited, a pestilence, silent and uncontrollable, would have accounted for the slaughter. But here four ships sailing at different periods, though all under favourable circumstances on the voyage, similarly visited.

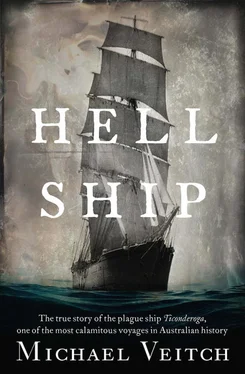

Till an investigation has taken place, let no man in his senses trust himself on board a Government emigrant ship. He may easily calculate his chance of getting to the end of the voyage. Here it is. The Ticonderoga had 800 souls on board at starting, and lost 104, including the doctor [ sic ]. The chance of being flung to the sharks is, therefore, just one in eight. People have usually been in the habit of considering themselves at least as well off in a Government emigrant ship as in a private one, but this is a delusion. We consider even Mr Rankin’s estimate of 600 persons in a ship as much too high. We should very much like some financial member of the House of Commons, to ask what sum was paid to the owners of this Ticonderoga . We are curious to know the particulars of this Government floating hospital, if only for the information of the colonists who send their money to be thus lamentably spent. If we recollect rightly, the Ticonderoga is not a British-built ship, but an old American liner; the receptacle of many a former cargo of Irish emigrants. We will not be positive on this point, but we do not expect to see the assertion contradicted. If the colonial legislatures, when they get the power of doing as they please with their own money, will aid societies like this, they will expend their money to some purpose, and we have no doubt that they will do so, as soon as the Emigration Commission has ceased to drain their exchequers.

* * * *

Back at Point Nepean, Dr Taylor, as Ferguson had suspected, was not coping. Although an experienced surgeon superintendent, having only recently in fact completed a relatively trouble-free run from England on the Ottillia, nothing in his experience could have prepared him—or anyone else—for the deluge of woe that awaited him at Point Nepean.

Conditions continued to be primitive in the extreme. Some people were lucky enough to be housed in the requisitioned cottages and tents, but most were confined to the hastily constructed canvas lean-tos that had been put together by the Ticonderoga ’s crew and able passengers. Some, remembered a Mrs Cain, daughter of the first permanent resident of Portsea, were confined to bark shelters, living like Aboriginal people, while their attendants and family ‘waved branches over them to keep off the flies’. [5] Welch, 1969, p. 33

Donald McDonald, in a description for a newspaper written decades later, recalls that at night his mother would have to shake the frost from the blankets covering their small beach lean-to made from timbers and ti-tree branches.

Читать дальше