In December 1945 one of these shrunken heads would play a dramatic role at the Nuremberg trials. The American assistant prosecutor, Thomas J. Dodd (who became the U.S. senator from Connecticut, a position later filled by his son, Christopher), addressed the court: “We do not wish to dwell on this pathological phase of the Nazi culture but we do feel compelled to offer one additional exhibit.” Then Dodd whisked away the white sheet covering United States Exhibit 254.

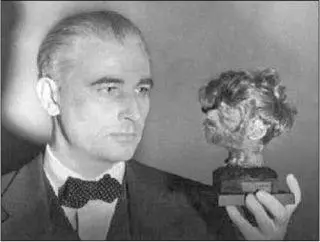

“A human head,” Dodd intoned. “A human head with the skull bone removed, shrunken, stuffed, and preserved.” It was, as Dodd said, echoing the words of Marlow upon visiting Kurtz’s upriver camp, “a terrible ornament.” If anyone still needed to be convinced of the barbarism that had seized the land of Goethe and Beethoven, here it was. In their malign, Faustian obsession with perfecting the human race, the Nazis had released the species’ basest instincts. After all, who else but jungle tribes, dark-continent cannibals bereft of contact with a merciful God, would shrink a human head? [10] Ideas expressed here owe a debt to Professor Lawrence Douglas’s article “The Shrunken Head of Buchenwald: Icons of Atrocity at Nuremberg.” Douglas’s discussion of the psychological motivation of the Nuremberg prosecutors is quite cogent. The article also includes the remarkable photo of Thomas Dodd holding a shrunken head in his hand, “like Hamlet contemplating the skull of Yorick.”

The presence of the shrunken head at Nuremberg served as a straightforward example of what was at stake in civilization’s clash with Nazism. In the case of the lampshade, however, this argument is not so clear. Constructed to run on electricity, the lamp on the Buchenwald Table is a thoroughly modern object, something that might be found in any bourgeois home. Rather than “a terrible ornament” harkening back to a savage past, the lampshade is a glimpse of a far more brutal time to come. With their dream of a thousand-year Reich, the Nazis were nothing if not ardent futurists. The stiff-jointed Tomorrowland they envisioned depended on the eradication of Jews and other contaminated beings. This accomplished, it would only be wise state policy (the Nazis being one of the first “green” regimes) to recycle the translucent, warm-toned skins of decommissioned individuals into items like lampshades, in the manner that the hides of cows eventually become leather jackets.

When Jewish skin became too scarce to mass-produce, the shades would become value-added collector’s items, relics of prehistory, exhibits to be gawked at by coming generations of Aryans, admonitory reminders of the times when Hebrews, insectlike carriers of society-destroying pestilence, still walked the earth.

Nuremberg prosecutor Thomas Dodd and a shrunken head

Indeed, Nuremberg might have been the last time someone like Thomas Dodd, a classic morally uplifted Yank, could realistically argue civilization’s side against the forces of atavistic primitivism. With the carnage wreaked by modern weaponry during the war, it was becoming more difficult to consider human progress an unalloyed boon. Science and technology were now the tools of a dystopian world to come; mankind was beginning to be viewed as the planet’s enemy rather than its salvation. (Even 1984 wasn’t written until 1949.) As the innate righteousness of the species was called into question, the argument that one group might be guilty of crimes against humanity was losing credence to the idea that genocidal incidents were really crimes of humanity. In this context, the lampshade, harbinger of a bleaker yet unavoidable technological future, would have proved more philosophically problematic for Nuremberg prosecutors than a shrunken head. The situation never came up, however.

By the time the war crimes trial began, the lampshade on the Buchenwald Table, ballyhooed as the handiwork of Ilse Koch and her paramours, had disappeared.

Shortly before the second anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Skip Henderson called to exercise his part-ownership rights (by this time I’d given him $17.50, which made us co-owners) to demand that the lampshade be donated to a Holocaust museum. The sooner the better.

“Since this thing appeared, it’s like my face has been shoved into hell,” Skip cried. He recounted an episode that had happened at St. Louis Cathedral in Jackson Square. He’d gone to mass, and while lighting a votive candle for his father, he was overcome.

“Suddenly I felt I was totally attached to everyone who had ever died in a horrible way. All the victims killed for no reason except they were who they were… every innocent, and maybe not-so-innocent person ever murdered on this earth. I started lighting candles. Candle after candle. All these people deserved candles, I thought. I must have lit, like, forty of them before this tourist standing there with his kids says, ‘Hey, buddy, we got people to mourn, too.’ I thought they were going to call the police. I had to go into the park and sit down.”

This was what had convinced Skip that the time had come to turn the lampshade over to “the professionals.”

Really, what else was there to do with it, short of flinging it out the window while doing sixty across the Huey P. Long Bridge? It wasn’t as if you could place the thing on one of those Germania militaria Internet venues that played vintage recordings of “Deutschland über Alles” as web surfers clicked through the usual array of SS Totenkopf Death’s Head Honor Rings, homoerotic Aryan gymnastics manuals, or the thousands of place settings of AH monogrammed flatware.

In Europe, you couldn’t even show much of this stuff in public, much less sell it. Antique toy soldier dealers in Berlin had to blot the Hakenkreuz off the arms of each tiny Wehrmacht man before displaying it. The U.S. market for Nazi collectables, however, was holding “solid.” According to a 2009 New York Times story, Nazi stuff was “recession proof.” Even replica sales were booming. Quick sellers on sites like the Rapid City, South Dakota—based PzG.biz (“Your Third Reich HQ!”) included “museum quality” copies of Zyklon B canisters marked “Konzentrationslager Auschwitz!—for display purposes only!”

People are often shocked to hear that many of the major collectors of Nazi “memorabilia” are Jews, some of them Holocaust survivors or their descendants. But this is not difficult to understand. If Hitler had purposely left Prague unbombed, with plans to make the city into a vast museum of “the extinct Jewish race,” why shouldn’t survivors collect relics of the extinct “master race”? Then again, one could explain the desire to amass Third Reich materials as simply as Lemmy, eternal guitar hero from the metal band Motörhead, did when he said, “Everyone knows the bad guys have the best uniforms.”

Still, you weren’t about to put a human skin lampshade on eBay, even if they allowed Nazi material or human remains, which they don’t. For sure you didn’t want to call up the venerable English Holocaust denier David Irving, who was running his own “Nazi eBay,” offering items out of his “vaunted personal collection” like a lock of Hitler’s hair, supposedly obtained by the Führer’s barber by putting a piece of sticky tape on the bottom of his shoe. Irving also claimed to have a bone fragment from Hitler’s ribs, which was going for a cool $180,000. As for the veracity of his product, he said, “When people come to my website and see the name David Irving, they know they are buying an authentic item. It is the gold standard.”

Читать дальше