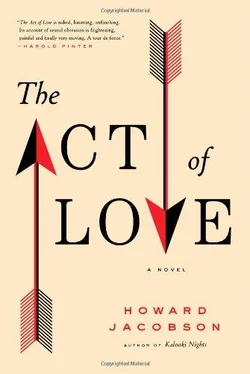

Howard Jacobson

The Act of Love

To Jenny — my one and only

The fever of the senses is not a desire to die. Nor is love the desire to lose but the desire to live in fear of possible loss, with the beloved holding the lover on the very threshold of a swoon. At that price alone can we feel the violence of rapture before the beloved.

Georges Bataille, Eroticism

‘I’ll tell you. . what real love is. It is blind devotion, unquestioning self-humiliation, utter submission, trust and belief against yourself and against the whole world, giving up your whole heart and soul to the smiter — as I did!’

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

FOUR O CLOCK SUITED THEM ALL — THE WIFE, THE HUSBAND, THE LOVER.

Four o’clock: when time in the city quivers on its axis — the day not yet spent, the wheels of evening just beginning to turn.

The handover hour, was how Marius liked to think of it.

Marius the cynic. Marius who held that natural selection gave the lie to God, and humanity the lie to natural selection. Marius who anticipated no more big adventures for himself, not even that last adventure left to modern man — ecstatic, immoderate, unseemly, all-consuming love. Marius who took pride in being beyond surprise or disappointment, there being nothing to expect of anybody, least of all himself. Marius the heartbroken.

He was thirty-five — though he looked and sounded older — tall and hazardously built, with a face suggesting ecological catastrophe: lost city of Atlantis eyes, blasted cheeks, a cruel, dried-up riverbed of a mouth. Women found the look attractive, mistaking their precariousness for his. Me too, though I was in every respect his opposite. I was the ecstatic he thought the world had done with. I am the one whom love consumes.

We’re all fundamentalists now, regardless of whether we’re believers or we’re atheists. One way or another you have to be devout. Marius worshipped at the altar of Disbelief. I at the altar of Eros. A god’s a god.

Faith is said to make you strong. My faith was of a different sort. I believed in order to be made weak. Love’s flagellant, in weakness I found my singularity.

Four o’clock it was, anyway. The handover hour. A conceit so lewd I can barely breathe imagining Marius imagining it.

As for who was handing over what, that is not a question that can be settled in a sentence, if it can be settled at all. The beauty of an obscene contract is that there’s something in it for everyone.

The wife, the lover, the husband.

I was the husband.

Here he is. In his black velvet jacket sumptuously lined with dark fur, he is a proud, handsome despot who plays with the lives and souls of men. . Under his icy gaze I am again seized with a deadly terror, a premonition that this man will capture and enslave her, that he has the power to subjugate her entirely. Confronted with such fierce virility I feel ashamed and envious.

Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, Venus in Furs

I FIRST SIGHTED MARIUS, LONG BEFORE I HAD ANY INKLING I’D HAVE USE FOR him — or he for me, come to that — at a country churchyard funeral in Shropshire. One of those heaving-Wrekin mornings the poet Housman made famous — rain streaming on stone and hillock, the gale plying the saplings double, a sunken, sodden, better to be dead than alive in morning. It didn’t matter to me, I was from somewhere else. I could slip on galoshes before I left my hotel, put up an umbrella, endure what had to be endured, and then be gone. But others at the graveside chose to live in this hope-forsaken place. Don’t ask me why. To assist in their own premature interment, is my guess. To be done with life before it could be done with them.

Such a lust for pain there is out there. Such apocalyptic impatience. I don’t just mean in Shropshire, though Shropshire might have more than its fair share of it, I mean everywhere. Bring on the dirty bomb, we cry, and publish instructions for its manufacture on the Internet. Blow winds and crack your cheeks: we scorch the earth, pitch our tent at the foot of a melting iceberg or disturbed volcano, sunbathe in the path of a tsunami. We can’t wait for it to be over. The masochists we are!

And all the while we have the wherewithal to suffer exquisitely and still live, if we only knew where to look. In our own beds, for example. In the beloved person lying next to us.

Love hard enough and you have access to all the pain you’ll ever want.

Not a thought I articulated at the time, I have to say, not having met, not having married, not having lost my heart and mind to the woman who would be my torturer. Marisa came later. But in the vegetative dark that preceded her, I never doubted that my skin was thinning in prepsaration for someone. Easy to be wise after the event and see Marisa as the fulfilment of all my longings, the one I’d been keeping myself for; but of course I didn’t fall in love only provisionally before I met her. Each time I lost my heart and mind, I believed I had lost them for good. Yet no sooner did I regain my balance than I knew that the woman who would finish me off completely — make me hers as I had never so far been anybody’s, a man possessed in all senses of the word — was still out there, waiting for her consummation as I was waiting for mine. Hence, I suppose, my interest in Marius, before I apprehended the part he would play in that consummation. I must have seen in him the pornographic complement to my as yet incompletely formed desires.

It was impossible to tell from his demeanour at the funeral whether he was one of the principal mourners. He looked sulkily aggrieved, scarfed up and inky-cloaked like Hamlet, but somehow, though he gave conspicuous support to the widow — a woman I didn’t know, but to whom there clung a sort of shameful consciousness of ancient scandal, like a fallen woman in a Victorian novel — I didn’t think he was the dead man’s son. His distress, assuming it to have been distress, was of a different order. If I had to nail it in a word, I’d say it was begrudging — as though he believed the mourners were weeping for the wrong person. Some men attend a funeral jealously, wishing to appropriate it for themselves, and Marius struck me as such a man.

I’d known and done a spot of business with the deceased. He had been a professor of literature with a large library. I had travelled up from London to value it. Nothing came of our negotiations. The library was ill-cared for and crumbled into dust before I could come up with a figure. A fortuitous event in its own way, since the professor did not really want to part with his books, whatever their condition. He was a sweet man, out of time and place, who expostulated against life’s cruelties in a squeak, like a mouse. One of life’s, now one of death’s, disappointees. But I hadn’t known him so well that I could move among his family and friends and ask them who the Black Prince was. As for striking up an acquaintance with him directly, that was out of the question. He was as obstinately sealed from eye contact or introduction as the corpse itself.

Observing him later, in the little centrally heated village hall to which we’d trooped after the service, plied double like the saplings, I wondered whether the bleak weather had been responsible for his appearance at the graveside, so much less saturnine was he, divested of his coat, his scarf and, if I wasn’t mistaken, the widow. To say he was merry would be to go too far, but he’d turned animatedly unapproachable, as opposed to simply unapproachable. A cold fire seemed to come off him, like stars off a sparkler.

Читать дальше