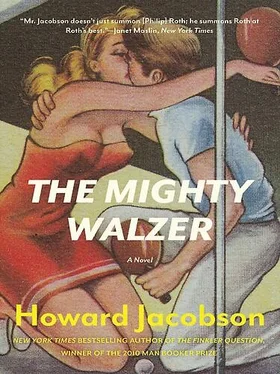

Howard Jacobson

The Mighty Walzer

For the boys of the J. L. B.

and G. O. S. J. ping-pong teams,

remembering the glory days.

The racket may be of any size, shape or weight.

4.1 The Rules

SMALL BEGINNINGS. The principle of the oak tree, and the secret of the successful artist, politician, sportsman. Nice and easy does it. A box of Woolworths watercolours for your birthday, a volume of Churchill’s speeches, a cricket bat or a pair of boxing gloves in your Christmas stocking. And then the slow awakening of genius.

Softly, softly, catchee monkey.

No small beginnings or slow awakenings for me, though. My sporting life was shot through with grandiosity from day one.

Grandiosity was in the family. On my father’s side. Normally, when I speak of ‘the family’ I seem to mean my father’s side. Make what you like of that. My mother’s side went in for reserve. And that too was something my sporting life was shot through with from day one. Can you be simultaneously grandiose and reserved? Not without great cost to yourself, you can’t. But let’s stick to my father’s side to begin with, if only because my mother’s side wouldn’t want to be intruding itself on anyone’s notice so early in the piece.

And let’s pin it to a date. August 5, 1933. Dates are important in sport. They remind us that achievement is relative. One day someone will run a mile in zero time; thanks to improved diet and training methods they will cross the tape before they’ve left the blocks. But back in the fifties four minutes looked pretty fast. On August 5, 1933, the first ever World Yo-Yo Championships were held in the Higher Broughton Assembly Rooms, not far from where the River Irwell loops the loop at Kersal Dale, on the Manchester/Salford borders. From my grandparents’ chicken-coop house in Hightown my father could walk to the Higher Broughton Assembly Rooms in twenty minutes. That was on an ordinary day. On August 5, 1933, he walked it in zero time. Excitement. He was twelve years old. And carrying his Yo-Yo in a brown Rexine travelling-bag.

The Yo-Yo craze had swept the country the year before. Cometh the hour, cometh the toy. A Yo-Yo was the perfect Depression analgesic. Every unemployed person could afford to own one. It passed the time while you were hanging around on corners or standing in a bread queue. And it conveyed a powerful subliminal message — nothing stays down for ever. It’s even possible that in some sort of way Yo-Yos were seen as an antidote to Fascism. Not just because of the multiplicity of bright colours they came in but because they bred individualism, introversion even. A kid playing with his Yo-Yo was a kid not marching behind Oswald Mosley. This may have been one of the reasons the Yo-Yo craze lasted so much longer in Manchester, which was a Black Shirt stronghold, than anywhere else. Though for the most likely explanation of Manchester’s irresistible rise to Yo-Yo capital of the world you need look no further than the weaver’s shuttle. They’d been spinning cotton here for two hundred and fifty years; they’d been weavers of wool, slubbers of silk, distaffers of haberdashery, ribboners and elasticators, for centuries prior to that. Wristiness was in their blood the way grandiosity was in mine. Playing with a Yo-Yo was no more than they’d been trained to do since the Middle Ages.

In the face of an adeptness as ancient and inwrought as that, it was fantastical of my poor father to suppose he had a hope of impressing at the World Championships, let alone of lifting the title itself, on which he’d set his heart. He may have been Mancunian in the sense that he’d begun his life in a Manchester hospital bed — ‘It’s a lad!’ were the very first words he heard, ‘and a biggun’ too’ — but there had been no other Mancunian of any size in our family before him, and you can’t expect to barge into an alien culture and lift all it knows of touch and artistry in a single generation. Bug country, that was where we came from, the fields and marshes of the rock-choked River Bug, Letichev, Vinnitsa, Kamenets Podolski — around there. And all we’d been doing since the Middle Ages was growing beetroot and running away from Cossacks.

He couldn’t count on much support at the Assembly Rooms either. The only person he’d told that he was competing was his father. And he only told him on the morning of the competition.

I imagine my grandfather sitting in his rocking-chair, looking into space, listening to the ticking of a clock. Grandfather clock, you see. That’s how we make our associations. Though in fact he wasn’t anybody’s grandfather then. The rocking-chair won’t be accurate either — that too belongs to a later time. But I’d be right about him looking into space. The one thing he wouldn’t have been doing was reading. There were no books and no newspapers on my father’s side. I don’t mean few, I mean none. Although he owned reading-glasses towards the end of his life, and liked opening and closing them, I never once saw my father reading anything except the instructions that came with whatever new shmondrie he was playing with and the notes my mother wrote (in capital letters and on lined paper) to help him with his patter when he was standing on the back of his lorry pitching out chalk ornaments on Oswestry market. He was so unfamiliar with books that when I presented him with mine (mine, ha! — some book, forty pages of black and white diagrams and dotted lines, illustrating the hows of the high-toss service and the topspin lob), he marvelled that I’d gone to the expense of having a special copy printed with the dedication for my father, Joel Walzer, who taught me to aim high. ‘Dad, it’s not a special copy,’ I had to explain to him, ‘they’re all dedicated to you. It’s called a print run.’

‘All of them? Sheesh! That’s very nice of you, Oliver.’

After that he took it everywhere with him — he would have taken the whole print run everywhere with him had it been practical — even to bed, my mother told me, where he’d sit up and stare at it for hours on end. ‘I think I’m beginning to get the hang of this,’ he told her one night. I asked her if she knew how far he’d got. Yes, she did as a matter of fact. He’d got to the bottom of the page opposite the dedication to him, where it says ‘This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, no part may be reproduced … without the prior permission of the publisher.’

But then who has time for books when they’ve a living to earn? And when their head’s full of big plans.

And big disappointments.

What my grandfather actually said on the morning I imagine him looking bookless into space I know from my father. He said, ‘Keep your voice down.’

‘It’s all right, she’s upstairs.’

‘And stairs don’t have ears? Use your loaf. Do you want to kill her?’

He did quite want to kill her, yes. They both did. But the real issue was did he want her to kill him. ‘No,’ he said.

‘Then hob saichel! Keep your voice down. What time are you on?’

My father wasn’t sure what time he was on. Only that he was contestant No. 180.

‘My advice to you,’ my grandfather whispered to him, looking anxiously at the ceiling, above which prowled the snorting beast, my grandmother, ‘is not to watch the previous one hundred and seventy-nine. Go somewhere quiet. See if you can find a dark place to sit, or better still lie down. And don’t show your face till they call your number. Now geh gesunterhait. If I can get away to come and watch you, I will. But if I can’t, have mazel.’

Читать дальше