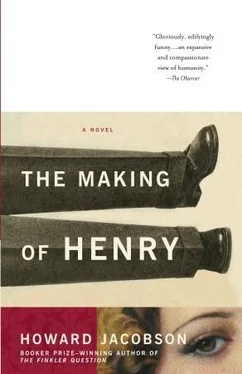

Howard Jacobson

The Making of Henry

For Jenny. . speaking of love

Huffy Henry hid the day

— John Berryman, 77 Dream Songs

Honour thy father and thy mother Exodus 20:12

Henry believes he knows exactly when the ninety-four-year-old woman in the neighbouring apartment dies. He hears her turn off. Until now he has not been able to distinguish her from her appliances — her washing machine, her vacuum cleaner, her radiators, her television. But the moment she gives up the ghost he detects the cessation of a noise of which he was not previously aware. A hum, was it? A whirr? Impossible to say. There is no word for the sound a life makes.

‘Ah well,’ his cleaning woman muses, once word of the death has seeped out, ‘what’s one more?’

‘Plenty, if you happen to be the one,’ Henry says.

She sidles a walled Irish eye towards his, oblivious to an Englishman’s partiality for space between two people not connected by marriage.

‘There we are, then,’ she says with a shrug, and goes on with the dusting. They’re all shrugging and dusting round here. Not on edge exactly, but fatalistic. Waiting to be blown apart. Henry isn’t thinking like that, though; Henry is just waiting for himself to die. There’s a subtle political difference. Never mind poison gas in the Underground, never mind helicopters crop-dusting the city with anthrax, Henry sees what’s coming as an entirely personal catastrophe, something between him and his Maker and no one else. That’s always been the trouble with Henry — he has never been able to grasp the larger picture.

Rather than remain in his apartment while there is a corpse next door, Henry ventures out. This is not something Henry normally enjoys doing. Nothing to do with anthrax. Out, in Henry’s view, is a madhouse. Historians of social lunacy will confirm that this is literally the case, that the mad have been let out of the asylums and allowed to walk the streets. But Henry doesn’t mean that. By mad, nerve-strung Henry means revving when you’re stationary and driving with your hand on your horn — read that sexually if you like, but Henry has in mind incessant honking — he means text messaging the person standing next to you, or being wired up so that you can speak into thin air, conversing with God is how it looks to Henry, or wearing running shoes when you’re not running, or coming up to Henry with a bad face and a dog on a piece of string and asking him for money. Why would Henry give someone with a bad face money? Because of the dog? Because of the string?

But there’s out and there’s out, and this out, Henry concedes, beats others he’s encountered. Still too much revving and honking and similar vehicular hectoring — inevitable, given the triple-parking which is the custom here: people nipping out of their cars to say hello to other people who have nipped out of their cars to say hello, and people boxed in by both sorts having heart attacks on their horns — but it’s a superior sort of hectoring, and the sports clothes, especially on the elderly, bespeak a greater gentility too, more cricketing and yachting than footballing — due, presumably, to the proximity of Lord’s and the boating lake in Regent’s Park. As for the bad-faced men with dogs, they rarely venture this far into the comfort zones of NW8. Neither did Henry much before now. Henry isn’t from here. As aren’t many of the people he sees in the street or bumps into in the lift, which accounts for much of the appeal the place has for him. It’s better to be a stranger among strangers, Henry reckons, no matter how jumpy everyone is, than to be even partially at home among the indigenous.

Prior to NW8, Henry had lived postcodeless and with the semi-permanent headache of the never quite settled anywhere, with one dry foot on the cobblestones of the town and one wet one in the drains and delfs of a moor so dour it was a miracle a single flower could find the will to bloom there, and few did. Walkers came and marvelled, but walkers are only ever passing through. As for the natives, Henry’s explanation to visitors to his rented crofter’s cottage was that they looked the way they did — blunt-nosed, crook-backed, mole-blind — as a consequence of never having moved from here since around about the end of the ice age, or whenever it was the great muds came. ‘Their heads grew beneath their shoulders as a matter of adaptational imperative,’ Henry went on, ‘and they’ve never been able to find a way of prising them out since.’ Assuming this to be a complaint about his environment, the less subtle of Henry’s visitors wondered what, in that case, he was doing living in a cold-water cottage by a delf. What did he expect, for God’s sake? At which Henry opened his eyes wide. He did not like people to talk ill of his heartlands. Ever since he could remember, Henry had woken up to a view fringed like an eyelash by the Pennines. The Pennines were his Mountains of Mourne. He attached lyrical significance to their green and purple. They were his Alps. They extended his conception of the possible. They were all foreignness and promise.

He should have stuck with the view. Down here, Henry is happier — which tells you something, since he isn’t happy — or at least he is more at home being not at home. But he hasn’t been here long. And wouldn’t be here at all if he still had his job, or his youth, or someone to love. And if it weren’t for the accident of a luxurious southern apartment — the one that has the dead old lady lying next door — passing into his possession.

The luxurious apartment is another reason why Henry would rather be in than out. Crystal chandelier over his bed, sunken bath, electronic drapes — press the keypad and the lights go on, the bath fills and the curtain closes — Henry has never lived so graciously before. The sound system is so good he cannot locate the speakers, he just gets music wherever he goes. A white bare-breasted mermaid, Saudi Arabian in conception, conceals the lavatory cistern, promising to press herself against him when he sits. She has a plastic plug in each of her nipples, from which, Henry initially deduced, fountains must play, though why you would want fountains playing down the back of your neck when you visit the lavatory, Henry had no idea. In the end he worked out that the plugs were simply to protect the nipples when the seat went up. But he is still feeling his way round the place and hasn’t given up finding fountains yet.

How it is that the apartment has passed into his possession Henry can explain, it’s the why that’s the problem. Because there’s a God, that’s why, would be Henry’s best shot, or at least his second-best shot at an explanation. Unless there’s a devil and NW8 is earmarked for destruction. The how is much easier. An envelope popped through the letterbox of his moor-land cottage, that’s how, just as he was considering his future, its contents a life-tenancy agreement with his name on — he takes it to be a life tenancy anyway, though he can’t be trusted to comprehend any piece of writing which isn’t what his profession calls ‘imaginative’ — and a letter from Shapira and Mankowicz, Solicitors, outlining the terms of the gift, to wit an obligation, as per the enclosed lease, to make no noise, to house no pets, to let off no firearms, and otherwise to ask no questions, in return for which he can expect to live unhampered and be told no lies. Henry doesn’t think it’s a mistake, Henry believes he can discern a bit of logic in it, but just in case he’s wrong, just in case someone else’s name should be on the lease, another Henry Nagel even more deserving than he is, he means to enjoy his good fortune before it’s taken away from him again. Like life itself.

Читать дальше