While ritual flaying for religious reasons would now be considered the sign of a barbaric culture, the practice is still very much with us in the commercial, pseudoscience realm. Body Worlds is a traveling anatomy exhibition in which skinned human corpses are displayed engaged in various activities, including a number of sexual positions. Relying on an embalming technique called “plastination,” which preserves human organs by the infusion of various silicons and epoxies, Body Worlds has been seen by more than thirty million people, many of them paying as much as forty dollars per admission. The brainchild of Dr. Gunther von Hagens, the son of an SS cook, who famously never appears in public without his trademark black fedora (he once performed a public autopsy in front of five hundred people while wearing the hat), Body Worlds is not without controversy. Questions have been raised about where those skinned bodies come from, and who gave permission for their use. Von Hagens has presented much documentation that his plastination shops in Dalian, China, and Kyrgyzstan are run according to local law, and that the remains were all donated with informed consent. That said, it is doubtful that any high school biology field trip visiting a Body Worlds show (or any of the similar, competing exhibitions) will see a skinless, epoxy-stuffed German, or any white European, exposing his insides while posed in the midst of kicking a brand-name soccer ball.

Perhaps the most influential flayer of human skin was not a bookbinder, shaman, plastinator, or organ dealer but rather one Ed Gein, a diminutive and seemingly unremarkable resident of windswept Plainfield, Wisconsin, population 889. Although he is often mentioned as the father of the modern serial killer, Gein (the name almost rhymes with “fiend”) was charged in the death of only two people, which puts him at the extreme low end of the body count scale. Still, his notoriety—Gein’s macabre deeds served as the basis for such resonant cultural touchstones as the Norman Bates character in Psycho, Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs, and Leatherface in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre —far outstrips the likes of Ted Bundy, Juan Corona, Wayne Williams, Dean Corll, Richard Speck, and many, many others. Much of Gein’s infamy owes to the time and place of his deeds. Even with the Nazi camps and the mass death at Hiroshima fresh in the mind, it was still considered unthinkable that such insanity lurked in the American heartland. It was shocking to hear that a strange but supposedly harmless little man (as Anthony Perkins said, he “wouldn’t hurt a fly”) kept a supply of severed human noses purloined from graveyards in a water glass and ripped the skin from the dead to upholster the furniture in his sitting room. In Gein’s case, the appalling thing was not the killing but the taxidermy.

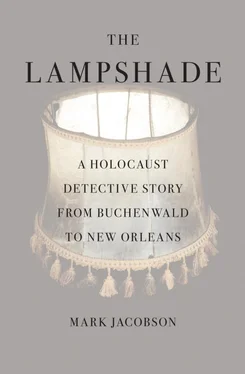

There is no evidence that Gein had any knowledge of Xipe Totec when he murdered hardware store owner Bernice Worden, from whom he’d just purchased a gallon of antifreeze, disemboweled her, and began wearing her skin around his soon-to-be-infamous farmhouse. However, local police did find books on Nazi medical experiments, including those done at Buchenwald, along with the lampshade Gein made of human skin.

The Nazi lampshade entered the wider American mind-set in a Billy Wilder production, or at least Wilder gets the director credit.

A true citizen of the bygone century, the director was born in 1906 in Galicia, then part of the teetering Austro-Hungarian Empire. By the late 1920s he was in Berlin, where he made his first films. He fled with the rise of Hitler, arrived in the United States during the middle 1930s, and claimed to have learned English by listening to baseball games on the radio. While Wilder is known for the caustic worldview on display in movies like Ace in the Hole, Double Indemnity, and Sunset Boulevard, it is emblematic of his particular American immigrant experience that the murder of his mother, stepfather, and grandmother at Auschwitz did not keep him from winning six Academy Awards and racking up boffo box office with “madcap comedies” like Some Like It Hot, which featured Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis playing cross-dressing jazz musicians.

Wilder’s contribution to lampshade iconography came in the service of the United States War Department, for which he oversaw the editing of Death Mills, a documentary that utilized graphic footage shot inside the liberated camps. Along with other newsreel compilations like Nazi Murder Mills, Wilder’s film played as a regularly scheduled feature at theaters throughout the United States.

“ Look! Don’t turn away!” narrator Ed Herlihy commanded from the soundtrack as the camp atrocities invaded the consciousness of the popcorn-munching masses. Much of this early footage was shot at Buchenwald, including a sequence recorded on April 16, 1945, five days after liberation, when the American high command marched some twelve hundred residents of Weimar up the Blood Road through Goethe’s forest to see what their countrymen had wrought.

The march was endorsed by Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower and his hell-or-high-water four-star general, George S. Patton, whose Sixth Armored Division had been the first to reach the camp. After an April 12 visit to Ohrdruf, a Buchenwald “satellite” camp thirty-five miles to the west, a visibly shaken Eisenhower said, “The things I saw beggar description. The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty, and bestiality were so overpowering.” In a much-quoted statement, the future president said he felt he had no choice but to see the camps personally, so as “to be in a position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.’” In contrast, despite such bluster as “We’re not just going to shoot the bastards, we’re going to cut out their living guts and use them to grease the treads of our tanks,” General Patton (subject of Richard Nixon’s favorite movie) declined to enter the camps. “He indicated that he would get sick if he did so,” Eisenhower said.

A lampshade allegedly to have been constructed on the orders of Ilse Koch appears several times in the footage shot the day of the Weimar march. It is visible as part of what is described by the narrator as “the parchment display,” an array of camp evidence Weimar residents were forced to view. Several views of the lampshade can be seen—a high-angle shot apparently from a rooftop and a number of fleeting close-ups. But the definitive shot is a still photo from that same day. Taken in front of the Buchenwald pathology lab, it shows three men, apparently newly freed prisoners, standing behind a table on which a number of gruesome objects are arranged as if part of a macabre show-and-tell exhibit. In the back row of specimens on what would come to be called the Buchenwald Table, or simply “the Table,” are a number of glass jars in which human organs—lungs, a heart, a stomach—float in formaldehyde. According to the prisoners, these organs were all that was left of the victims of botched SS medical experiments.

In front of the jars, held down by rocks against the wind, sit several pieces of tattooed human skin. Among the tattoos are a cowboy wearing a ten-gallon hat, an Indian chief in a flowing headdress (images of the American frontier were popular in Germany), a pornographic picture of a woman with her legs spread apart, another of a bare-breasted woman sprouting large butterfly wings, and others in a similar mode.

On the Table’s left-hand side sit a pair of shrunken heads. Set on small wooden pedestals, the heads, reduced to the size of a human fist and featuring long, flowing dark hair, were said to have been made from the remains of Polish workers hanged for engaging in racially forbidden intercourse with German women. According to a 1950 article in Der Spiegel, Ignatz Wegener, a prisoner in the Buchenwald medical ward, helped prepare the heads after reading about the process in a book about the South American Jivaro tribe. The heads were then displayed in the camp barracks as a cautionary note to inmates.

Читать дальше