“You mean, like, from Canada?”

“Says it right on there.”

The girl looked at the coin. “Guess I didn’t see that. Shit. Canada’s next door. I thought it was far,” she said, deflated. Sullen once more, she said she couldn’t give me her aunt’s number, but I could leave mine. “What am I supposed to say you want?” Seeing no downside, I explained a bit about the lampshade.

The girl looked horrified. “You think it was in this house? They found it here? That’s terrible!”

“I didn’t say it was from here,” I said, attempting to backtrack. “I’m trying to find out about a story I heard.”

The baby started to fuss as the girl gave me that look, like if she lived to be a thousand, she’d never understand why white people say and do the things they do. “You looking for something that used to be a person,” she said. “People I know—they’re looking for people that are still people.”

• • •

In his book The Theory and Practice of Hell, the first comprehensive account of life in a Nazi concentration camp and in many ways still one of the most informative, Eugen Kogon, a conservative Austrian Catholic who was a political prisoner at Buchenwald from 1939 to 1945, describes the daily routine of the place. Awoken as early as four in the morning by whistles, prisoners were given a meager breakfast of weak coffee and a piece of bread and then made to assemble in the Appellplatz, the wide-open field between the inmate barracks and the entrance gate, for roll call.

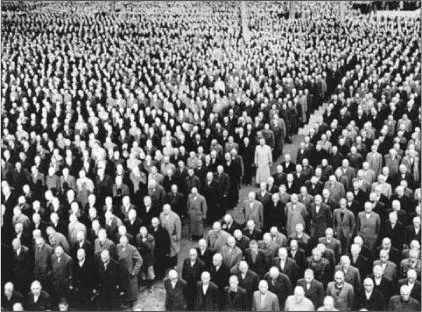

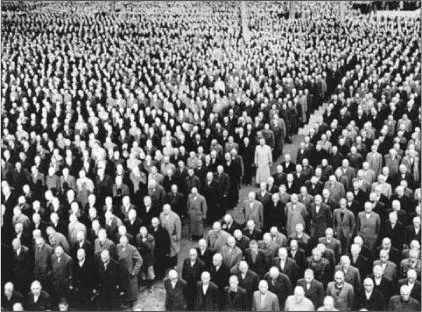

Prisoners at Buchenwald roll call

“Thousands of zebra-striped figures of misery, marching under the glare of the floodlights in the haze of dawn, column after column—no one who has ever witnessed it is likely to forget the sight,” writes Kogon, describing how the various categories of prisoners were denoted by color-coded SS-issued triangular patches sewn onto their clothing. The “politicals” bore a red triangle, “criminals” green, black was for the “work shy” and the “asocial,” purple for Jehovah’s Witnesses (described in camp parlance as “Bible researchers”), and pink for homosexuals. Jews wore the infamous yellow triangle. If a Jew was deemed to also fall into any of the other groups, the appropriate colored triangle would be sewn over the yellow one to make a Jewish star. At the morning roll call, the prisoners would line up—as many as twenty-five thousand forced laborers, slaves, really—to be sent out to their various work details in the quarries, machine shops, and pigsties, and in the evening were reassembled in the same spot.

The evening roll call included the dreaded head count, which often took hours, since if anyone was missing, the entire camp was made to stand at attention until the absent prisoner was found. Kogon recounts one such occasion. In December 1938, the prisoners were assembled on the Appellplatz for nineteen hours in subzero temperatures, motionless except for incessant commands to remove their caps from their shaven heads and put them back on again.

“Twenty-five had frozen to death by morning; by noon the number had risen to more than seventy,” he writes. Kogon describes a similar situation the preceding winter when prisoners were forced to strip naked for a number of hours, a sight which attracted “the wife of Kommandant Koch, in company with the wives of four other SS officers,” who came “to the wire fence to gloat at the sight of the naked figures.”

One recurring feature at roll call was the singing of “The Buchenwald Song,” always accompanied by the camp band. The song was commissioned by SS Major and Deputy Camp Kommandant Arthur Rödl, an alcoholic Karl Koch crony and member of the Nazi “Blood Order,” indicating party membership dating back to the days of the Munich Beer Hall Putsch. Other camps had songs, so Buchenwald should have one as well, Rödl declared, offering ten marks to any prisoner writing an acceptable tune. Many proposals were turned down before an entry submitted by a “green” criminal but actually written by a pair of Austrian Jews was accepted. Apparently either unaware of or unconcerned with the underlying subversiveness of lyrics like “O Buchenwald, I cannot forget you/For you are my Fate… We will say yes to life/For the day will come when we are free!” Rödl ordered each prisoner to learn the song. Appearing at roll call “stinking drunk,” he would snap, “Sing ‘The Buchenwald Song’!” He’d require the inmates to stand for hours in driving rainstorms until the piece was rendered to his satisfaction.

The Jews had their own song, which they were forced to sing repeatedly, often at the command of the SS officer Hermann Florstedt, who, after the transfer of Karl Koch to Lublin, was widely reported to have been Ilse Koch’s lover. Entitled “The Jew Song,” it went, “For years we wreaked deceit upon the nation/No fraud too great for us, no scheme too dark/All that we did was cheat and swindle/Whether with dollar, pound, or mark/But now, at last the Germans know our nature/And barbed wire hides us safely out of sight… And now, with mournful crooked Jewish noses/We find that hate and discord were in vain/An end to thievery, to food aplenty/Too late, we say, again and yet again.”

At one time, anyone standing on the Appellplatz could have seen most of the camp. It would have been possible to scan the array of prisoner barracks, small wooden shacks called “blocks,” fanned out in lines of eight and ten, the “children’s blocks” set behind them. To the side would have been the medical experiment blocks, with their tile-topped tables on which Nazi doctors went about their harsh rounds of yanking gold teeth and stripping skin from the dead. Also visible, of course, would be the crematorium and its squat smokestack, where, prisoners grimly joked, the exhaust of their existence would soon be rising.

I thought that seeing these things would provide context, a way to collate the experience of standing in the cold wind with what can be read in books and seen in movies. It was in and around those doom-laded bunkhouses that Margaret Bourke-White, traveling with Patton’s army, took her famous photos of the bodies that Edward R. Murrow, in an anguished on-site radio broadcast, said were “stacked like cordwood.” But most of the camp structures were torn down by the Soviets in the early 1950s before they turned the place over to their East German clients, who, in the interests of their “antifascist” cause, memorialized the vanished buildings by filling their footprints with piles of stones.

On the day I arrived, I saw nothing from the Appellplatz . The winter Ettersberg fog had descended and was so thick I could barely make out my feet. The last, sparse tourist group had long since filed onto their bus and gone down the Blood Road, and I was alone, marooned on the Appellplatz, enveloped in the fog like a gauze-wrapped mummy.

Years before, in Phnom Penh, I’d visited Tuol Sleng, a former high school that became the notorious S-21 prison, where the Khmer Rouge tortured and murdered more than fourteen thousand people between 1975 and 1979. What happened at Tuol Sleng (“Hill of the Poisonous Trees” in Khmer) was as hideous as anything ever attempted by the Nazis. The chilling photo gallery of the victims and the list of “security regulations” still hang on the wall: “4: You must answer my questions without wasting time to reflect.” “6: When getting lashes or electrification you must not cry out at all.” Still, when the harrowed visitor leaves Tuol Sleng, he steps back into the world. On the other side of the fence, outside the prison entrance, people bustle by, deliverymen go about their business, motorcycle taxi—men hang out beside their scooters smoking cigarettes, the bougainvillea blooms. The Buchenwald Appellplatz was not like that. Socked in by the fog, it was as if the end of the line had been reached, with nothing but abyss ahead.

Читать дальше