* * *

The men from the Académie Royale de Médecine were on hand within hours. They wanted a cast of the body. Deputations of anatomists followed; they wanted the body itself. How they got it is a murky affair, but within days the dissection of l’enfant bicéphale was announced. In the vast amphitheatre of the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, Ritta and Christina were laid out in state on a wooden trestle table. The anatomists jostled for space around them. Baron Georges Cuvier, France’s greatest anatomist – ‘the French Aristotle’ – was there. So was Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, connoisseur of abnormality, who in a few years would lay the foundation of teratology. And then there was Étienne Reynaud Augustin Serres, the brilliant young physician from the Hôpital de la Pitié, who would make his reputation by anatomising the girls in a three-hundred-page monograph.

Beyond the walls of the museum, Paris was enthralled. The Courier Français intimated that the medical men had connived at the death of the sisters; they replied that the magistrates who had let the family sink to such miserable depths were to blame. The journalist and critic Jules Janin published a three-thousand-word j’accuse in which he excoriated the anatomists for taking the scalpel to the poetic mystery that was Ritta and Christina: ‘You despoil this beautiful corpse, you bring this monster to the level of ordinary men, and when all is done, you have only the shade of a corpse.’ And then he suggested that the girls would be a fine subject for a novel.

The first cut exposed the ribcage. United by a single sternum, the ribs embraced both sisters, yet were attached to two quite distinct vertebral columns that curved gracefully down to the common pelvis. There were two hearts, but they were contained within a single pericardium, and Ritta’s was profoundly deformed: the intra-auricular valves were perforated and she had two superior vena cavas, one of which opened into the left ventricle, the other into the right – the likely cause of her cyanosis. Had it not been for this imperfection, lamented Serres, and had the children lived under more favourable circumstances, they would surely have survived to adulthood. Two oesophagi led to two stomachs, and two colons, which then joined to a common rectum. Each child had a uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes, but only one set of reproductive organs was connected to the vagina, the other being small and underdeveloped. Most remarkably of all, where Christina’s heart, stomach and liver were quite normally oriented, Ritta’s were transposed relative to her sister’s, so that the viscera of the two girls formed mirror-images of each other. The anatomists finished their work, and then boiled the skeleton for display.

A PAIR OF LONG-CASE CLOCKS

The oldest known depiction of a pair of conjoined twins is a statue excavated from a Neolithic shrine in Anatolia. Carved from white marble, it depicts a pair of dumpy middle-aged women joined at the hip. Three thousand years after this statue was carved, Australian Aborigines inscribed a memorial to a dicephalus (two heads, one body) conjoined twin on a rock that lies near what are now the outskirts of Sydney. Another two thousand years (we are now at 700 bc), and the conjoined Molionides brothers appear in Greek geometric art. Eurytos and Cteatos by name, one is said to be the son of a god, Poseidon, the other of a mortal, King Actor. Discordant paternity notwithstanding, they have a common trunk and four arms, each of which brandishes a spear. In a Kentish parish, loaves of bread in the shape of two women locked together side by side are distributed to the poor every Easter Monday, a tradition, it is said, that dates from around the time of the Norman conquest and that commemorates a bequest made by a pair of conjoined twins who once lived there.

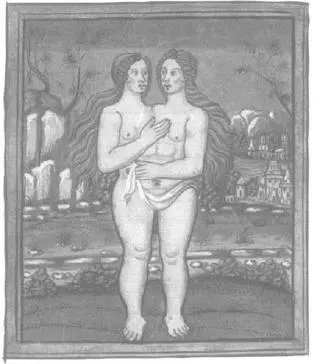

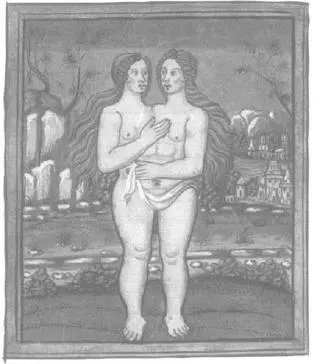

By the sixteenth century, conjoined twins crop up in the monster-and-marvel anthologies with the monotonous regularity with which they now appear in British tabloids or the New York Post . Ambroise Paré described no fewer than thirteen, among them two girls joined back to back, two sisters joined at the forehead, two boys who shared a head and two infants who shared a heart. In 1560 Pierre Boaistuau gave an illuminated manuscript of his Histoires prodigieuses to Elizabeth I of England. Amid the plates of demonic creatures, wild men and fallen monarchs, is one devoted to two young women standing in a field on a single pair of legs, flaming red hair falling over their shoulders, looking very much like a pair of Botticelli Venuses who have somehow become entangled in each other.

For the allegory-mongers, conjoined twins signified political union. Boaistuau notes that another pair of Italian conjoined twins were born on the very day that the warring city-states of Genoa and Venice had finally declared a truce – no coincidence there. Montaigne, however, will have none of it. In his Essays (c.1580) he describes a pair of conjoined twins that he encountered as they were being carted about the French countryside by their parents. He considers the idea that the children’s joined torsos and multiple limbs might be a comment on the ability of the King to unify the various factions of his realm under the rule of law, but then rejects it. He continues, ‘Those whom we call monsters are not so with God, who in the immensity of his work seeth the infinite forms therein contained.’ Conjoined twins did not reflect God’s opinion about the course of earthly affairs. They were signs of His omnipotence.

CONJOINED TWINS: PARAPAGUS DICEPHALUS DIBRACHIUS. NORMANDY. FROM PIERRE BOAISTUAU 1560 HISTOIRES PRODIGIEUSES.

By the early eighteenth century, this humanist impulse – the same impulse that caused Sir Thomas Browne to write so tenderly about deformity – had arrived at its logical conclusion. In 1706 Joseph-Guichard Duverney, surgeon and anatomist at the Jardin du Roi in Paris, the very place where Ritta and Christina had been laid open, dissected another pair of twins who were joined at the hips. Impressed by the perfection of the join, Duverney concluded that they were without doubt a testament to the ‘the richness of the Mechanics of the Creator’, who had clearly designed them so. After all, since God was responsible for the form of the embryo, He must also be responsible if it all went wrong. Indeed, deformed infants were not really the result of embryos gone wrong – they were part of His plan. Bodies, said Duverney, were like clocks. To suppose that conjoined twins could fit together so nicely without God’s intervention was as absurd as supposing that you could take two long-case clocks, crash them into each other, and expect their parts to fuse into one harmonious and working whole.

Others thought this was ridiculous. To be sure, they argued, God was ultimately responsible for the order of nature, but the notion that He had deliberately engineered defective eggs or sperm as a sort of creative flourish was absurd. If bodies were clocks, then there seemed to be a lot of clocks around that were hardly to the Clockmaker’s credit. Monsters were not evidence of divine design: they were just accidents.

The conflict between these two radically different postitions, between deformity as divine design and deformity as accident, came to be known as la querelle des monstres – the quarrel of the monsters. It pitted French anatomists against one another for decades, the contenders trading blows in the Mémoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences . More than theology was at stake. The quarrel was also a contest over two different views of how embryos are formed. Duverney and his followers were preformationists. They held that each egg (or, in some version of the theory, each sperm) contained the entire embryo writ small, complete with limbs, liver and lungs. Stranger yet, this tiny embryo (which some microscopists claimed they could see) also contained eggs or sperm, each of which, in turn contained an embryo… and so on, ad infinitum . Each of Eve’s ovaries, by this reasoning, contained all future humanity.

Читать дальше