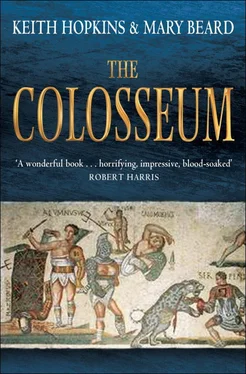

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But Roman society did not fit as easily as we often like to imagine into straightforward vertical status groups and the seating in the Colosseum probably blurred the legal distinctions as much as reinforcing them. Was it only the senators who sat in the ringside seats? Or could they bring guests and clients? Did some slaves actually sit at the front with their elite masters, or did the senators pay for their exclusivity by having to do without their everyday attendants at the ringside? We do not know the exact area of the senatorial seating (there is no precise archaeological indication of how far it extended), but the best guess would suggest that it offered space for 2000 spectators, assuming that they had twice as much space as the people in the squashed rows behind. There were only about 600 senators, and many of those would have been out of Rome at any one time (commanding the army, governing the empire). We are left with one of two conclusions. Either senators in practice occupied about eight times as much space as the ordinary citizen, which even by Roman standards of inequality seems extreme. Or seating in this area was in practice socially mixed, not just senatorial sons, but friends and contacts too.

There were other factors which would upset the neatness of the stratification of the Colosseum and other groups who found a place in its system, cutting across the official hierarchy. Fragments of inscriptions, for example, have been discovered which originally identified collective seating for ‘boys’ and probably also for their tutors (who, though usually slaves, would have presumably sat near their charges); another marks out space for ‘citizens of Cadiz’. It seems very probable that other groups such as official delegations, artisans or traders from big cities acquired the right to sit in particular places, whether by favour or purchase, quite separately from their formal place in the legal hierarchy. In the later empire, individual aristocrats had their names carved in marble to indicate their personal or family seating space. The Colosseum was not, as is sometimes implied, simply a place where the political collectivity of Rome was on view; it displayed individual variance, power and influence too.

And what proportion of that collectivity would be included in the audience anyway? Almost no one now believes the late Roman account which seems to suggest that there were 87,000 seats in the Colosseum; at best, it has been argued (though for no particularly strong reason), this really meant 87,000 feet of seating space, not individual seats. Modern estimates cluster around an estimated capacity of about 50,000. But Rome in the first century AD is thought to have had a population of one million, which suggests some 250,000 adult male citizens. On this reckoning, even when it was completely full, the Colosseum would have held only one fifth of those citizens, and even less in that some space was taken up by women, boys, slaves and outsiders. Our guess is that, even though the shows were free, the poor and the very poor were systematically under-represented (as they are in most social benefit systems in any place or at any period). If this is correct, the audience at the Colosseum was more of an elite of white toga-clad citizens than the rabble proletariat often imagined today.

THE EMPEROR – IN AND OUT OF THE BOX

The emperor was the sponsor of the most spectacular shows in the Colosseum, which he watched in the presence of his people from the imperial box in a prominent position at the centre of one of the long sides of the arena’s oval. Ancient writers devote so much attention to the emperor’s role at these Colosseum shows that it is now hard to recapture any image of the monument without the imperial presence or to recover any information on shows that were sponsored by ‘ordinary’ aristocrats. That is partly the point. For the Colosseum quickly became one of the key contexts (if not the key context) in which the emperor’s quality and worth were judged.

‘Good’ emperors were defined as such by their behaviour in the arena: they generously showered the audience with presents or tokens that could later be exchanged for yet more valuable objects; they offered lunch (or at least the ancient equivalent of a cheeseburger and Coke in their seats) to the onlookers; they never ever looked bored with what was going on, never used the privacy of their box to get on with some paperwork, but they did not take too much pleasure in the shows either (a difficult tightrope to tread, no doubt, between disdain and fanaticism). They also sprang witty surprises. It was presumably in the Colosseum that an emperor in the middle of the third century AD, Gallienus, played an ingenious trick on a man who had sold his wife glass jewels instead of real gems. He is supposed to have ordered the man to be taken off as if to be thrown to the lions, but when the cage was opened, a capon tottered out. The emperor had his herald proclaim to the astonished audience, ‘He practised deceit and had it practised on him.’

‘Bad’ emperors were just the opposite. Typically they were supposed to transgress the boundaries on which the logic of the shows rested, most obviously by turning themselves into gladiators and the audience into victims. The notorious emperor Caligula, in the mid first century AD, about fifty years before the Colosseum itself was built, is said to have been so short of criminals for execution that he had some of the spectators thrown to the beasts instead. Domitian, among others, had members of the Roman elite fighting as gladiators. But it was the emperor Commodus (as in the movie) who offers the most vivid case of the intersection of the emperor’s image with gladiatorial combat.

Commodus was assassinated in AD 192, by a lethal consortium of his mistress, chief chamberlain and commander of the guard. They had supposedly discovered his plans to kill them all, which the emperor had carelessly left written on a wooden tablet, when he fell into a drunken sleep after lunch. Besides, Commodus was also said to have been planning on the very next day, 1 January 193, to murder the consuls and present himself as holder of this traditional office dressed not in a toga, but as a Roman gladiator, emerging to meet the people not from the palace but from the gladiatorial training camp where he had lodgings. True or not, it is the closest we ever come in Roman history to the image of the emperor being, as it were, completely re-branded as a gladiator. And it goes along with all kinds of other evidence for the promotion of the figure of ‘emperor-as-gladiator’ during Commodus’ reign. He is supposed to have fought hundreds of gladiatorial bouts himself (in private, it was said, these were fights to the death, or at least he clipped off a few of his opponents’ noses; in public it was display bouts only, with wooden swords and no bloodshed). According to a late scandalmongering biographer, which may at least reflect rumour at the time, he had the great statue of the Colossus altered so that it bore his own features, and his titles inscribed at the base of the statue included two new imperial sobriquets: ‘Gladiator’ and ‘Cross-dresser’ (in Latin, ‘ Effeminatus ’). When he was assassinated, the gleeful acclamations of the senate apparently included the refrain ‘Cast the gladiator into the charnel house’.

The most extraordinary account of Commodus’ exploits in the arena comes from the historian and senator Dio, who was himself an eye-witness to many of them from his ringside seat in the Colosseum: ‘I was there myself and I saw and heard everything and took part in what was spoken; so I have thought it right to suppress no details, but to hand them down just as they happened, just like anything else of the greatest weight and importance.’ On one occasion, Commodus opened the extravaganza by killing a hundred bears with spears, throwing them from specially constructed walkways which divided up the arena. As Dio implies, this was more a demonstration of accuracy than courage – but even Edward Gibbon, whose tart denunciation of these antics in the Colosseum is a marvellous set-piece in Decline and Fall , was forced to concede that ‘some degree of applause was deservedly bestowed on the uncommon skill of the Imperial performer’. The next day he killed some relatively harmless domestic animals, some of which were in nets in any case (just to be on the safe side presumably), plus a tiger, hippo and elephant. That was a morning’s work. In the afternoon he fought a demonstration bout as a gladiator, armed with a shield and wooden sword, against an opponent armed only with a wooden pole. Unsurprisingly, Commodus won, and then settled down to watch the real bouts – some of which he oversaw from a platform in the arena, dressed up as the god Mercury.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.