Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

LIONS AND CHRISTIANS

Whatever the death rate of gladiators in the Colosseum, it must have been much worse for the beasts which took part in the shows. There were many more animals than humans involved in the arena displays – both killed and killing. For the big spectaculars at least, the practical arrangements for their capture, transportation and handling must have demanded time, ingenuity and personnel far beyond the acquisition and training of the gladiators. Not for Romans the tame pleasures of a modern zoo, safe entertainment for young children and indulgent grandparents (though who knows if some perhaps did visit the animals kept before the show in the Animal House near the Colosseum). Their chief pleasure was in slaughter, either of the animals or by them. Sophisticated this may sometimes have been, in elegantly constructed settings, rocks and trees appearing in the arena as if from nowhere, or tableaux of execution cleverly mimicking (as Martial evokes) the stories of mythology. But it is hard to see how the end result could have been anything other than a morass of dead flesh. As we saw, Dio’s total of animal deaths at the shows opening the Colosseum was 9000, and 11,000 at Trajan’s shows in 108–9. Even if we suspect exaggeration on the part of either emperor or historian, and even if (as must be the case) these lavish spectacles were the exception rather than the norm, there can be no doubt that we are dealing with, for us, an uncomfortable amount of animal blood.

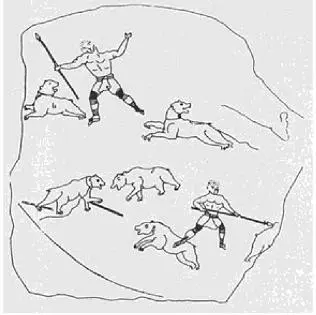

It seems that animal hunts and displays often took place in the morning of a spectacle, conducted by a special class of trained hunters and animal handlers. Though not gladiators in the strict sense of the word (and without the charisma of gladiators in Roman culture), these venatores and bestiarii (‘hunters’ and ‘beast men’) were almost certainly drawn from the same underclass, slaves and the desperate poor. One of the training camps in Rome was called the Morning Camp; and it was here, we guess, that these men were trained for the job. Part of their act was to lay on animal displays, the cranes battling cranes, for example, which Dio reported among the highlights of the Colosseum’s opening, or what appears to be a fight between a bull and a mounted elephant on a coin of the early third century, showing the Colosseum. Part was more straightforward hunting. To judge from surviving images in paintings and mosaics, marksmen mostly on foot, but some on horseback, picked off the animals with spears, swords and arrows. It is hardly too fanciful to imagine that graffiti on one of the marble steps in the Colosseum itself, showing scantily clad spearmen rounding up some hounds and chasing or taking aim at a group of bears, represent what the doodling artist was watching, hoped to see or fondly remembered as taking place in the arena (illustration 17).

Most ancient writers assume that the outcome of these contests was death for the animals (and presumably in the process for some of the hunters); in fact when listing the total carnage, they tend to note the number of gladiators who fought , but the animals which were slain (suggesting that survival was an option for the former, but not for the latter). Modern scholars have occasionally flirted with the idea that some of these acts may have been ‘exhibitions’, in the sense that the animals survived. In fact one idea has been that a particular rhinoceros extolled by Martial for its victory over a bull at the inaugural Colosseum games is exactly the same animal as a rhinoceros mentioned in a later book of Martial’s poetry, written under the emperor Domitian, and none other than the rhino commemorated on some coins of Domitian. He was an animal star, in other words, with several bouts to his credit, much on the lines of star gladiators. Maybe. But we cannot help thinking that a degree of modern sentimentality is creeping in here – although the sheer trouble and expense of acquiring such rare specimens might always have made saving their lives for future appearances a prudent economic move.

The accounts we have of the animal hunts and shows always lay most stress on the fierce and exotic. In the middle of the first century BC, the great general Pompey (Rome’s answer to Alexander the Great until he was defeated in civil war by Julius Caesar) is said to have laid on, amongst other creatures, twenty (or seventeen depending on who you believe) elephants, 600 lions and 410 leopards. The emperor Augustus, in his autobiography, boasts of ‘finishing off’ a combined total of 3500 animals in ‘African beast hunts’ in the course of his reign (according to Dio, this included thirty-six crocodiles on one occasion). One notoriously unreliable late Roman historian let his imagination run away with him, we must hope, when he listed the animals shown by the emperor Probus in the Circus Maximus (‘planted to look like a forest’) in the late third century AD: ‘a thousand ostriches, a thousand stags, a thousand boars, then deer, ibexes, wild-sheep and other herbivores’. On a fantastical variant of the usual procedure, the people were said to have been let in to take what animals they wanted. The same emperor, on another occasion, is said (by the same historian) to have put on a rather disappointing show in the Colosseum. It included a hundred lions which were killed as they emerged sluggishly from their dens, and so ‘did not offer much of a spectacle in their killing’.

The logic of these shows is clear enough. Whether fact or fiction, the killing (and the tales told about it) vividly dramatised Rome’s conquest of the (natural) world. It would, for example, have been hard to watch the slaughter of Augustus’ crocodiles without reflecting on the fact that Egypt had just been brought under direct Roman control. But the practicalities of handling all these animals must surely baffle us. This is partly a question of managing these dangerous creatures in the arena itself. Even if not when it first opened, the Colosseum was eventually equipped with an elaborate system of hoists and cages, which could have delivered animals from the basements, through trapdoors into the arena. But it is hard to imagine how the big animals could have been reliably controlled with the strings and whips that are shown on most of the surviving visual images. Maybe that would have been sufficient for the sort of animals that we suspect made up the regular fare at the Colosseum, the ones ancient and modern writers and artists are much less interested in: the goats, small deer, horses and cattle, even rabbits. With the large and dangerous specimens of the celebrity occasions, things could and did go nastily wrong. Pompey’s elephants, for example, caused all kinds of problems in the Circus in 55 BC. The crowd reputedly much enjoyed the elephant crawling on its knees (its feet wounded too badly for it to stand up) snatching shields from its opponents and throwing them up in the air like a juggler. But it was hardly such fun when the beasts en masse tried to break out of the palisading that enclosed them. It caused, as Pliny remarks in a disconcertingly deadpan way, ‘some trouble’ in the crowd.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.