Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It is even more amazing to contemplate the organisation and expertise that must underlie the acquisition and transport of these wild animals. True, if we think of the more run-of-the-mill shows, then probably the animals could be supplied by local livestock markets – and some emperors apparently kept a herd of elephants just outside Rome, under the charge of a ‘Master of the Elephants’. But – that apart – how were the more impressive and exotic victims obtained? The scale of the problem of animal procurement can be gauged by a single comparison. In 1850 a young hippo was brought to western Europe, the first for more than a thousand years, and caused a great stir in London, where it ended up in the Regent’s Park Zoo under the name of Obaysch. It took a whole detachment of Egyptian soldiers and a fivemonth journey from the White Nile to transport it as far as Cairo. A specially built steamer equipped with a 2000-litre water tank took it from Alexandria to London, accompanied by native keepers, two cows and ten goats to provide it with milk. Compare that with the five hippos, two elephants, a rhino and a giraffe killed (according to an eye-witness account) by the emperor Commodus himself in a single twoday exhibition in the late second century AD.

How did the Romans do it? How did they capture the animals in the first place, without the convenient aid of the modern tranquillising dart? The answer seems to be by a variety of traps and pits and the cunning use of human decoys dressed up in sheepskins! And how did they manage to get these fierce and no doubt frightened creatures delivered from distant parts of the empire to the capital alive and in good fighting condition? Sceptics will answer that they often did not. Symmachus, after all, was disappointed with his emaciated bear cubs and maybe more corpses arrived than living animals. All the same, behind the exaggeration and the failures that are not trumpeted in ancient literature, the stubborn reality remains that on occasion at least large numbers of these beasts did make it to Rome. Private enterprise and personal arrangement played their part. In the late 50s BC, as we know from his surviving letters, Cicero, the new governor of the province of Cilicia (in modern Turkey), was being badgered to get hold of some panthers for shows of his disreputable friend Marcus Caelius; Cicero was evasive, claiming that the animals were in short supply. But later it seems that state requisitioning of animals also made use of army detachments. It was perhaps a convenient way of keeping the troops occupied while on peacetime garrison duty. We know from inscriptions, for example, of a ‘bear-hunter’ serving with the legions on the Rhine and of fifty bears captured in six months in Germany.

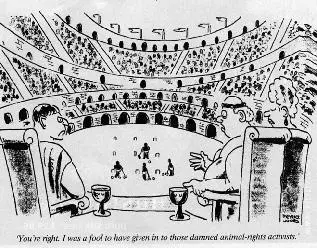

Animals were not only brought to the Colosseum in order that they themselves should be killed. They were also used to kill criminals and prisoners in the executions that took place in the arena as part of the shows. One notorious form of execution was ‘condemnation to the wild beasts’ (‘ damnatio ad bestias ’), where prisoners, some tied to stakes, were mauled and eaten by the animals. This is the fate to which Christian prisoners were often sentenced and is the origin of all those novels and films which take as their centrepiece the clash between ‘Christians and Lions’, not to mention the series of sick jokes along the lines of ‘Lions 3, Christians 0’.

The fact is that there are no genuine records of any Christians being put to death in the Colosseum. It was only later (as we shall see in Chapter 6) that Christian writers invested heavily in the Colosseum as a shrine of the martyrs. No accounts of martyrdoms there are earlier than the fifth century AD, by which time Christianity had become the official religion of Rome; they look back to the conflicts between Christians and the Roman authorities centuries earlier. It is likely that Christians were put to death there and that those said to have been martyred ‘in Rome’ actually died in the Colosseum. But, despite what we are often told, that is only a guess.

One of the possible candidates for martyrdom in the Colosseum is St Ignatius, a bishop of Antioch (in Syria) at the beginning of the second century AD, who was ‘condemned to the beasts’ at Rome. His writings, and those of other Christians describing death in the arena, not only offer a different perspective on the amphitheatre from the point of view of the victim, but also show how important that ideology of victimhood was in the community of the early church. Of course, we know next to nothing of the actual death experience of Christian martyrs, but Ignatius’ letters, apparently written to the community of Christians in Rome on the journey to the city for his death, are full of highly charged, and blood-curdling, anticipations of the moment. He was going to his death voluntarily:

Let me be fodder for the wild beasts; that is how I can get to God. I am God’s wheat and I am being ground by the teeth of wild beasts to make a pure loaf for Christ… What a thrill I shall have from the wild beasts which are ready for me… I hope that they will make short work of me. I shall coax them to eat me up at once, and not hesitate, as sometimes happens, through fear. Forgive me, I know what is good for me… Come fire, cross, battling with wild beasts, wrenching of bones, mangling of limbs, crushing of my whole body, cruel tortures of the devil, only let me get to Jesus Christ.

What is astonishing in Ignatius’ letter is the degree to which he and his intended audience internalised ‘pagan’ ideals about death in the arena and subverted them to their own ends. The cruelty and suffering of the arena are now idealised as instruments of believers’ salvation.

St Ignatius’ letter is not an isolated example of Christian fixation with the arena. From the second century onwards Christians created a new genre of literature, known as ‘Martyr Acts’, which celebrated the capture and trial (often before a capricious pagan judge) of a steadfast Christian who was willing to suffer terrible tortures and death rather than give up his or her faith. Hugely embellished no doubt, they acted as a kind of sacred pornography of cruelty, tying the Christian message to gruesome and gory death at the hands of the Roman authorities. One of the most vivid and shocking is the account of the martyrdom of two female saints, Perpetua and Felicity, at the beginning of the third century AD in Carthage. After the narrative of their trial and imprisonment, the story turns to their final moments in the amphitheatre. They were brought out, at first naked and tied up in nets, to face ‘a mad heifer which the Devil had prepared’; their male friends had faced leopards, bears and boars. But, apparently, even the crowd was horrified at the sight of the two young women, one of whom – Felicity – had just given birth, her breasts still visibly dripping milk. So they were taken off, dressed again in tunics and sent back to the arena. Tossed and crushed, they nevertheless remained alive, until the crowd demanded their execution in full view. Perpetua’s killer was a novice, and – despite the agony caused by his mishits – she guided his sword to her throat. ‘O most valiant and blessed martyrs. Truly you are chosen for the glory of Christ Jesus our Lord.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.