Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard

WONDERS OF THE WORLD

THE COLOSSEUM

PREFACE

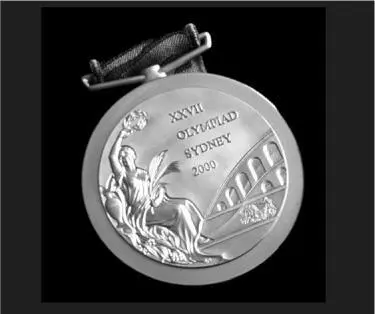

The Colosseum is the most famous, and instantly recognisable, monument to have survived from the classical world. So famous, in fact, that for over seventy years, from 1928 to 2000, a fragment of its distinctive colonnade was displayed on the medals awarded to victorious athletes at the Olympic Games – as a symbol of classicism and of the modern Games’ ancient ancestor.

It was not until the Sydney Games in 2000 that this caused any controversy. British newspapers – most of which did not know that the Colosseum had been gracing Olympic medals for more than half a century – enjoyed poking fun at the ignorance of the antipodeans who apparently had not grasped the simple fact that the Colosseum was Roman and the Games were Greek. The Australian–Greek press took a loftier tone; as one Greek editor thundered, ‘The Colosseum is a stadium of blood. It has nothing to do with the Olympic ideals of peace and brotherhood.’

The International Olympic Committee wriggled slightly, but stood their ground. They had already prevented the organisers of the Games replacing the Colosseum with the profile of the Sydney Opera House, so they presumably had their arguments ready. The design, they insisted, was traditional and it was not, in any case, the Roman Colosseum specifically, but rather a ‘generic’ Colosseum: ‘As far as we are concerned, it’s not important if it’s the Colosseum or the Parthenon. What’s important is that it’s a stadium.’

Unsurprisingly, the Colosseum motif had been replaced by the time the Games went (back) to Greece in 2004. The ponderously titled ‘Committee to Change the Design of the Olympic Medal’ came up with a new, Greek and much less instantly recognisable design: a figure of Victory flying over the Panathinaikon stadium built in Athens to host the first modern Games in 1896. But the questions that this argument raised about the Colosseum itself still remain. What was its original purpose? (Certainly not the racing signalled by the miniature chariot also depicted on the medal.) How should we now respond to the bloody combats of gladiators that have come to define its image in modern culture? Why is it such a famous monument?

These are just some of the questions we set out to answer in this book.

1

THE COLOSSEUM NOW…

COLOSSEUM BY MOONLIGHT

In 1843 the first edition of Murray’s Handbook to Central Italy , the essential pocketbook companion for the well-heeled Victorian tourist, enthusiastically recommended a visit to the Colosseum (or the ‘Coliseum’ as it was then regularly spelled). Many aspects of Rome, it warned, would prove inconvenient or disappointing. The Roman system of timekeeping was simply baffling for the punctual British visitor; its twenty-four-hour clock began an hour and a half after sunset, so times changed with the seasons. The local cuisine left a lot to be desired (‘A good restaurateur is still one of the desiderata of Rome’, moaned the Handbook , somewhat sniffily). Accommodation too could be difficult to find, especially for those with special requirements – the invalids who were recommended to search out rooms with ‘a southern aspect’, or the ‘nervous persons’ advised to ‘live in more open and elevated situations’. Yet the Colosseum was guaranteed not to disappoint. In fact, it was even more impressive in real life than its reputation might suggest: ‘There is no monument of ancient Rome which artists and engravers have made so familiar to readers of all classes… and there is certainly none of which the descriptions and drawings are so far surpassed by the reality.’ No need then to promote its virtues or guide the visitor’s response. ‘We shall not attempt to anticipate the feelings of the traveller,’ the Handbook continued, ‘or obtrude upon him a single word which may interfere with his own impressions, but simply supply him with such facts as may be useful in his examination of the ruin.’

A brisk account followed, with plenty of dry dates, dimensions and figures. Building work started under the emperor Vespasian in AD 72, with the opening ceremonies under his son Titus in 80; the last recorded wild beast show in the arena took place in the reign of Theodoric (who died in AD 526) – unless you count a bull-fight staged in 1332. The whole structure covered some 6 acres and was built of travertine stone (mixed with brick in the interior). Its outer elevation comprised four storeys, to a total of 157 English feet, with eighty arches on the ground floor giving an entrance to seats and arena. Inside, the arena measured 278 by 177 feet and was originally surrounded by seating in four separate tiers which could accommodate, according to one late Roman description, 87,000 spectators. And so on. But, in traditional guidebook style, the pill of these facts and figures was sugared by the occasional curious myth, anecdote or arcane piece of knowledge. Hence the reference to a story put about by the Church, in a fit of wishful thinking, that the architect of the Colosseum had actually been a Christian and a martyr by the name of Gaudentius; and hence the account of the plans of Pope Sixtus V in the sixteenth century to convert the whole building into a wool factory, with shops in the arcades – a scheme which, even though abandoned, came at enormous financial cost to the pontiff. There were also misconceptions to be corrected. Those puzzling little holes all over the building were not, as many people had said, where poles had been inserted to support the booths erected for the medieval fairs that took place there. They were instead (and this is still thought to be the correct explanation) where enterprising medieval hucksters had dug into the structure to remove and make off with the iron clamps which held the blocks together.

Helpful hints were offered too on how to make the most of a visit. The important thing, then as now, was to get as high up on the building as possible. For the Victorian visitor, a special staircase had been constructed to give access to the upper storeys ‘and thence as high as the parapet’. From here, where there was a view both into the Colosseum itself and out over such notable antiquities as the Arch of Constantine, the Palatine Hill and the Roman Forum, ‘the scene… is one of the most impressive in the world’. If this might seem perilously close to an ‘attempt to anticipate the feelings of the traveller’, then even more so was the insistence that the view was best at night, by the light of the moon. ‘There are few travellers who do not visit this spot by moonlight in order to realise the magnificent description in “Manfred”, the only description which has ever done justice to the wonders of the Coliseum.’ As if to underline the point, and to tell the visitor exactly how to react, a substantial chunk of Lord Byron’s ‘Manfred’ was quoted, with its famous comparison of the night-time impact of the standing – albeit ruined – Colosseum (‘the gladiators’ bloody Circus’) and the paltry and overgrown remains of what had once been the palace of the Roman emperors (‘Caesar’s chambers, and the Augustan halls’) on the Palatine:

I do remember me, that in my youth,

When I was wandering, – upon such a night

I stood within the Coloseum’s wall,

Midst the chief relics of almighty Rome;

…

…Where the Caesars dwelt,

And dwell the tuneless birds of night, amidst

A grove which springs through levell’d battlements,

And twines its roots with the imperial hearths,

Ivy usurps the laurel’s place of growth; –

But the gladiators’ bloody Circus stands,

A noble wreck in ruinous perfection!

While Caesar’s chambers, and the Augustan halls,

Grovel on earth in indistinct decay. –

And thou didst shine, thou rolling moon, upon

All this, and cast a wide and tender light,

Which soften’d down the hoar austerity

Of rugged desolation, and fill’d up,

As ’twere anew, the gaps of centuries.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.