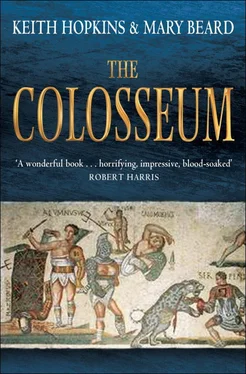

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Thanks in part, no doubt, to their appearance in the Handbook , these lines became one the most influential ways of ‘seeing’ the Colosseum, and were dramatically declaimed, or repeated sotto voce , by countless Victorian (and later) visitors to the monument.

For the rest of the nineteenth century, succeeding editions of Murray’s Handbook continued to insist that moonlight was the prime time to appreciate the Colosseum and to give detailed instructions on whether special permission was needed and, if so, how to obtain it. By 1862 an even more atmospheric option was available for the most plutocratic of tourists, a private light show: ‘The lighting-up of the Coliseum with blue and red lights, a splendid sight, can be effected, having previously obtained the permission of the police, at an expense of about 150 scudi, everything included.’ One would hope that it was ‘all inclusive’; at the rate of exchange with the pound advertised in the Handbook , 150 scudi is not far short of an adult manual worker’s annual wage in England at the time. No surprise perhaps that, after Rome became capital of the united Italy in 1870, such an extravaganza was taken over by the public authorities. The 1881 edition of the Handbook advised that the ‘illumination of the Colosseum with white, green and red lights, a splendid sight, takes place generally once a year, on the Natale di Roma (21 April), or on the occasion of some royal persons visiting the Eternal City.’ Even if the moon failed, in other words, the Birthday of Rome would always offer a dramatically floodlit Colosseum.

ROMAN FEVER

Yet scratch the surface of this apparently up-beat image of nineteenth-century tourism to the Colosseum and some rather more uncomfortable aspects emerge. This was partly a question of Protestant anxieties about the Catholic ‘takeover’ of the monument. A cross in the middle of the arena and a series of shrines at the edges were one thing – appropriate commemoration of the Christian martyrs who had supposedly lost their lives there. The idea that, as the Handbook had it, kissing the cross bought ‘an indulgence of 200 days’ was quite another. Equally awkward (even if it offered a picturesque vignette of primitive piety) was the ‘rude pulpit’ near by, from where a monk preached every Friday. The best you could say was that it was ‘impossible not to be impressed with the solemnity of a Christian service in a scene so much identified with the early history of our common faith’ (though, even then, the phrase ‘our common faith’ must have been a hard-working euphemism).

There was also, predictably, the question of how far the romantic image of the lonely Colosseum by moonlight, so heavily advertised by the Handbook and other guides, was a self-defeating piece of propaganda. The impression we get elsewhere is that the Colosseum by night could be, by nineteenth-century standards at least, far too crowded and far too un-romantic for comfort. For example, in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Marble Faun (1860), set among a group of expatriate artists in Rome, a moonlit visit to the monument involves negotiating a host of other visitors, laughing and shrieking, flirting and playing peek-a-boo among the shadowy arcades. Hawthorne paints a vivid picture of mindless tourism. One party was singing (drunkenly, we are meant to imagine) on the steps of the central cross; another, English or American, following the instructions of the Handbook to the letter and ‘paying the inevitable visit by moonlight’, had climbed up to the parapet and were ‘exalting themselves with raptures that were Byron’s not their own’. No chance for silent contemplation of the wonders here.

At the same time, though, it was possible to feel frustrated that in some respects the commercial possibilities of the monument had not been sufficiently realised. One of the glories of the Colosseum, until it was aggressively weeded and tidied up in 1871, was the vast range of flower species that had colonised its nooks and crannies – well over 400 different types, according to the most systematic study (illustration 30, p. 179). Why on earth, wondered the Handbook in 1843, was not more done with these? ‘With such materials for a hortus siccus [a collection of dried flowers], it is surprising that the Romans do not make complete collections for sale, on the plan of the Swiss herbaria; we cannot imagine any memorial of the Coliseum which would be more acceptable to the traveller.’

But all these were side-issues compared with the central problem that faced any visitor who knew something of the history of the building. How could one reconcile the magnificence of the structure, the scale and impact of what remained, with its original function and the memories of bloody gladiatorial combat and Christian martyrdom that had taken place in its arena? The Handbook skirted the problem briefly but awkwardly – and without even pointing explicitly to the human carnage that had been wreaked in the Colosseum: ‘The gladiatorial spectacles of which it was the scene for nearly 400 years are matters of history, and it is not necessary to dwell upon them further than to state that at the dedication of the building by Titus, 5000 wild beasts were slain in the arena, and the games in honour of the event lasted for nearly 100 days.’

Many others in the nineteenth century, however, visitors and writers alike, did feel a need to dwell on what had happened there and to debate the effect it must have on their appreciation of the monument. It is a theme that underlies Byron’s verses quoted earlier (how come that this monument of cruelty survives when the imperial palace has left such paltry traces?) and it was harped on too by Charles Dickens when he visited Italy in the 1840s (‘Never, in its bloodiest prime, can the sight of the gigantic Coliseum… have moved one heart as it must move all who look upon it now, a ruin. God be thanked: a ruin!). But the debate is perhaps most sharply dramatised in Madame de Staël’s novel Corinne , when the exotic poetess who is the heroine of the book takes her Scottish admirer Lord Oswald Nelvil on a guided tour of the sights of Rome. The highlight of the day was the Colosseum, ‘the most beautiful ruin in Rome’, Corinne enthused. But Oswald (who was, frankly, rather a prig) ‘did not allow himself to share Corinne’s admiration. As he looked at the four galleries, the four structures, rising one above the other, at the mixture of pomp and decay which simultaneously arouses respect and pity, he could only see the masters’ luxury and the slaves’ blood.’ Despite her spirited defence of her position, Corinne signally failed to convince him that it was possible to appreciate the magnificence of the architecture separately from any disgust for the immoral purpose it had once served. ‘He was looking for a moral feeling everywhere and all the magic of the arts could never satisfy him’; nor in the end could the magic of Corinne.

In fact, the Colosseum repeatedly appears in nineteenth-century literature as a site of tragedy and an emblem of death, both ancient and modern. For memories of the slaughter of gladiators went hand in hand with the belief that the damp and chill evening air of the monument – romantic moonlit vista though it may have been – was a particularly virulent carrier of the potentially fatal malarial ‘Roman fever’. (This notorious danger of the Roman air is discussed in detail by the Handbook , in a section – significantly – placed directly after the description of the Protestant cemetery.) It was Roman fever that carried off Henry James’ Daisy Miller after she had flouted social convention to spend the evening in the Colosseum alone with her Italian admirer, Signor Giovanelli. ‘Well, I have seen the Colosseum by moonlight… That’s one good thing’ she shouted defiantly, in what were almost her last words, to her other admirer, and critic, the ineffectual Mr Winterbourne (who was also lurking in the Colosseum, where he had been murmuring – what else? – ‘Byron’s famous lines out of Manfred ’). The moonlit Colosseum proves only slightly less treacherous in Edith Wharton’s brilliantly satirical short story from the 1930s, ‘Roman Fever’, which exposes the shady past of two middleaged American matrons – Mrs Slade and Mrs Ansley – who are spending the afternoon together in a restaurant close to the Colosseum. In little more than a dozen pages, it comes to light that, years earlier, just before their respective marriages, Mrs Slade, suspicious of her fiancé’s interest in the other woman, had tricked Mrs Ansley into spending a perilous evening in the Colosseum. She had caught a nasty chill there, it is true. But, more to the point, as is revealed in the last line, she had also conceived her lovely daughter Barbara in its shadows – by Mr Slade. The Colosseum’s association with death and flirtation is here neatly rolled into one.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.