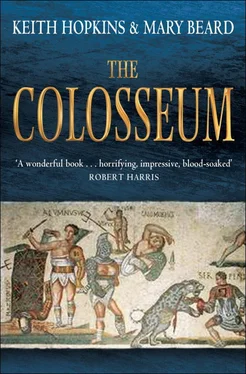

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Egypt , forbear thy Pyramids to praise,

A barb’rous Work up to a Wonder raise;

Let Babylon cease th’incessant Toyl to prize,

Which made her Walls to such immensness rise!

Nor let th’ Ephesians boast the curious Art,

Which Wonder to their Temple does impart.

Delos dissemble too the high Renown,

Which did thy Horn-fram’d Altar lately crown;

Caria to vaunt thy Mausoleum spare,

Sumptuous for Cost, and yet for Art more rare,

As not borne up, but pendulous i’th’Air:

All Works to Caesar ’s Theatre give place,

This Wonder Fame above the rest does grace.

Of course, Martial was not an impartial witness. As the in-house poet of the imperial court, one might argue, it was his job not simply to reflect the fame of the monument but to use his art to make it famous . If so, then he was strikingly successful, as a vivid account (by the late-Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus) of the visit of the emperor Constantius II to Rome in AD 357 suggests. Constantius had been emperor for twenty years but had never actually been to the capital before; most of his reign had been spent dealing with the Persians in the East and with rivals to his throne in other parts of the empire. Combining public business with some energetic sightseeing around the attractions of the city, he is said to have been very struck by the ‘huge bulk of the amphitheatre’. True, there were other monuments also reported to have caught his attention, and pride of place seems to have gone to Trajan’s Forum, where he stood ‘transfixed with astonishment’. But the Colosseum was not far behind, a building so tall that ‘the human eye can hardly reach its highest point’.

It was not just a matter of literary fame, however. Perhaps the clearest indication of the monument’s importance in the Roman world is the rash of imitations it spawned. Although there were several earlier stone amphitheatres, once the Colosseum had been built it seems to have become the model for many, if not most, of those that followed, both in Italy and in the provinces – well over two hundred by the end of the second century AD on current estimates. The façade of the Capua amphitheatre in southern Italy, for example, which seems to have had a succession of columns in the different architectural orders – Tuscan, Ionic and Corinthian – immediately evokes its predecessor in Rome. Further afield, the third-century amphitheatre at El Jem in modern Tunisia (which still dominates its modern town almost as dramatically as does the Colosseum) seems to have been designed so closely on the pattern of the Roman example as to be in effect ‘a shrunken Colosseum’. Exactly how the design was copied or what technical processes of architectural imitation were involved, we do not know. But somehow the Colosseum became an almost instant archetype, a marker of ‘Romanness’ across the empire.

A variety of factors combined to give the Colosseum this iconic status in ancient Rome. As the reaction of Constantius implies, size was certainly important. It was, by a considerable margin, the biggest amphitheatre in the empire; in fact some of the more modest structures, such as those at Chester or Caerleon in Britain, would have fitted comfortably into the space of the Colosseum’s central arena. But size was not everything. The strong association of both the form and function of the building with specifically Roman culture also played a part. Many individual elements of the design certainly derived from Greek architectural precedents, but the form as a whole was, unusually, something distinctively Roman – as were the activities that went on within it (even if gladiatorial spectacles were later enthusiastically taken up in the Greek world). A key factor too was the role of the Colosseum in Roman history and politics. For it not only signalled the pleasures of popular entertainment, it also symbolised a particular style of interaction between the Roman emperor and the people of Rome. It stood at the very heart of the delicate balance between Roman autocracy and popular power, an object lesson in Roman imperial statecraft. This is clear from the very moment of its foundation: its origins are embedded in an exemplary tale of dynastic change, imperial transgression, and competition for control of the city of Rome itself.

‘ROME’S TO IT SELF RESTOR’D’

The history of the Colosseum goes back to the year AD 68, when after a flamboyant reign the emperor Nero committed suicide. The senate had passed the ancient equivalent of a vote of no confidence, his staff and bodyguards were rapidly deserting him. So the emperor made for the out-of-town villa of one of his remaining servants and (with a little help) stabbed himself in the throat – reputedly uttering his famous boast, ‘What an artist dies in me!’ (‘ Qualis artifex pereo ’), interspersed with appropriately poignant quotes from Homer’s Iliad . Eighteen months of civil war followed. The year 69 is often now given the euphemistic title ‘Year of the Four Emperors’, as four aristocrats, each with the support of one of the regional armies (Spain, Danube, Rhine and Syria) competed for succession to the throne – wrecking the centre of Rome in the process and burning down the great temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. But the end result was the victory of a coalition backing Titus Flavius Vespasianus, now usually known simply as ‘Vespasian’.

Vespasian was the general in charge of the Roman army suppressing the Jewish rebellion which had erupted in 66. After a long siege and huge loss of life, Jerusalem was captured and ransacked under the immediate command of Vespasian’s son, Titus, in 70. Scurrilous Jewish stories, preserved in the Talmud, told how Titus had desecrated the Holy of Holies by having sex with a prostitute on the holy scriptures (a sacrilege avenged by the good God who sent a flea which penetrated Titus’ brain, drummed mercilessly inside his skull and – as was revealed by autopsy – caused a tumour which eventually killed him). Some Roman stories were hardly less fantastic. It was said that while still in the East Vespasian, as newly declared emperor, legitimated his rule by a series of miracles (curing the lame with his foot and the blind with the spittle from his lips). In fact, more prosaically, the emperor and prince spent a leisurely time in the rich eastern provinces raising taxes to repair the damage to state finances caused by Nero’s extravagances. They returned to Rome – first Vespasian, then Titus – to celebrate a joint triumph over the Jews in 71.

This triumphal procession proclaimed the end of civil war, the supreme power of the Roman state and popular hopes for future happiness; or so we are told by a writer who may well have witnessed the ceremony, the historian Josephus, once himself a rebel Jewish commander, now a turncoat favourite at the Roman court. The two generals, dressed in ceremonial purple costume, travelling in a chariot drawn by white horses, made their way through the streets of Rome. In the procession, the conquering soldiers displayed a selection of their prisoners (apparently Titus had specially chosen the handsome ones) and their booty to cheering crowds: a mass of silver, gold, ivory and precious gems. Large wagons, like floats in a modern carnival, were decorated with huge pictures of the war: a once prosperous countryside devastated, rebels slaughtered, towns destroyed or on fire, prisoners praying for mercy. And from the Temple of Jerusalem itself there came curtains ripped from the sanctuary (and destined to decorate Vespasian’s palace), a scroll containing the Jewish Law, a solid-gold table and the seven-branched candelabra, the Menorah, whose image still clearly stands out on the triumphal arch in honour of Titus at the east end of the Forum (illustration 6). On the ruined Capitoline hill, the procession halted in front of the Temple of Jupiter Best and Greatest. Only after Simon son of Gioras, the defeated Jewish general, had been executed did Vespasian and Titus say prayers and sacrifice; the people cheered and feasted at public expense. Rome’s imperial regime was safely restored.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.