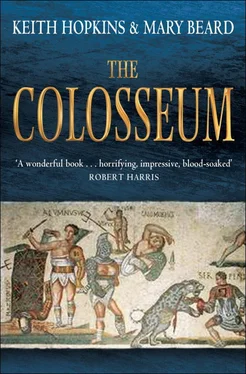

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Dio insists that when the emperor was fighting, the senators and knights always attended. Only one principled character stayed away, who would rather have died (literally) than be forced to watch all this or join in the chanting that was required of the elite: ‘You are lord, and you are first, and the most blessed of all. Victor you are, and victor you will be…’ The common people, however, had more choice than their betters and were much more inclined to give the proceedings a miss, partly out of disgust, partly because they had heard a rumour that the emperor was planning to shoot some of the spectators, in the guise of Hercules shooting the Stymphalian birds. (This must have been one of those occasions when even an imperial blockbuster in the Colosseum was not playing to a full house.) Not that the senators were any less anxious. Dio in fact describes one particular unforgettable incident which panicked as much as it disgusted and amused the senators in the front rows. Commodus had just killed an ostrich in the arena and cut off its head. Approaching the senators in the audience he held up the ostrich head in his left hand and a bloody sword in his right and, without speaking, grinned at them – as if to say that he would or could do much the same to them. ‘And,’ to quote Dio’s exact words, ‘many of us would have died by the sword there and then, for laughing at him (for it was laughter not indignation that took hold of us), if I had not myself chewed on some laurel leaves which I picked from my garland, and persuaded the people sitting near me to do the same, so that we might conceal the fact we were laughing by the steady movement of our jaws.’

In this story, the Colosseum is the setting for one of those very rare occasions when we can, almost physically, empathise with the Romans. We know exactly what that laugh of Dio’s – caused by a mix of hilarity and sheer terror – would have felt like. And most of us have vivid memories, from school if not later in life, of suppressing a giggle that would inevitably get us into trouble by biting our lips, a sweet paper, a ruler or whatever. But what on earth was going on in these extraordinary gladiatorial antics by the emperor? In part, as we suggested earlier, the arena and the gaze of the people sets up a competition for popular attention between emperor and performers. It is one of those awful ambivalences of Roman imperial power: the emperor sponsors the show, but always risks being upstaged by the déclassé stars of the fighting; yet he is bound to humiliate himself if he decides to direct the people’s gaze to himself by usurping the position of the fighter. The Colosseum was, in other words, a venue that is central to the emperor’s image as benefactor of his citizens, but one in which he found it hard to win. In part too, as Dio’s tale of the ostrich head waved in front of the senators must hint, the arena provided a context for the display not so much of the Roman collectivity, but of its conflicts and fissures. The bitter rivalry between aristocrats and emperors is a leitmotif of Roman history. And yet there they were, staring at each other across the Colosseum. It is hardly surprising that the two sorts of conflict (fighter versus beast; emperor versus senate) were repeatedly intertwined, that one infected the other, that one was used as a means of fighting the other. In short, the Colosseum dramatised the emperor’s struggles with himself and with his rivals.

VIEWS AND COUNTER-VIEWS

What, finally, did the spectators think of what they saw in the arena? Modern accounts tend to divide ancient reactions into far too simple categories. Most Romans (bloodthirsty culture that Rome was) did not disapprove of the shows. A few oddballs, such as Seneca, expressed their revulsion. Christians, for obvious reasons, saw in them the cruelty of Roman paganism to which they were so strongly opposed. We have already seen several reasons to query this simple picture. Martial’s poetry hinted that the touchstone of approval/disapproval was not necessarily appropriate for understanding his response to the events in the arena. Despite all the Christian attacks on the institution, ‘sincere’ as many of these undoubtedly were, the rise of Christianity, as we have argued, was paradoxically tied to the violence of the amphitheatre. In the case of Seneca, he may have expressed his horror at the executions at midday, but he was nonetheless there in the arena (not) watching, and in his philosophical work he could use gladiatorial combat as a positive model in ethics.

The fact is that Romans (or at least the elite Romans whose words survive) were reflective about their own culture, the culture of the arena included. Their reactions to it were certainly different from our own, but there is no reason to suppose that they were any less complicated. Roman historians and anthropologists, for example, wondered about where the different elements of the shows – especially the gladiators and the animal hunts – came from and what their original function had been. They claimed to know that, long before the regular arena performances, the first display of gladiators in Rome had happened in 264 BC as part of the funeral celebrations of a leading aristocrat. This funerary connection was developed by Tertullian and other early Christian writers to suggest that this form of combat lay in human sacrifice to the spirits of the dead, thus damning its very origin with the worst religious crime of all, for Christians and pagans alike. (Despite the obviously ideological slant of this theory, modern scholars often repeat it as if it were known fact.) Other ancient writers were more interested in the geographic origins of the gladiators. A Greek historian in Rome under the emperor Augustus, puzzled by the Roman practice of sometimes bringing on gladiators at the end of a dinner party, linked it with customs in Etruria and claimed an Etruscan origin for gladiators as a whole. This has sent modern scholars scurrying off to the paintings in Etruscan tombs, where they claim (unconvincingly in our view) to have found traces of proto-gladiatorial combat. For others, both ancient and modern, Campania, south of Rome, seemed, or seems, the most likely home of the first gladiators – which fits conveniently, though not necessarily significantly, with the fact that the earliest surviving stone amphitheatres are in this part of Italy.

Romans also reflected on the ethics of the arena, with many of the doubts, ambivalences and contradictions we ought to expect. So, for example, Marcus Aurelius, Commodus’ father (unless we believe that story about Faustina’s gladiator lover), claimed in the sixth book of his philosophical ramblings, euphemistically known as the Meditations , to have found gladiatorial shows ‘boring’. And in 177, in his reign (along with his son Commodus as coruler) the legislation we used in our calculations of gladiator numbers was prefaced with one of the most striking criticisms of the cruelty of the shows that is recorded in Roman history. In abolishing the tax on the sale of gladiators, the authorities argued that the treasury ‘should not be stained with the splashing of human blood’ and that it was morally offensive to get money from what was ‘forbidden by all laws of gods and humans’. What Commodus’ attitude to this was we can only guess! But even with Marcus Aurelius himself there are odd contradictions; not least of which is the fact that in AD 175 he himself had apparently put on a massive show at Rome with 2757 gladiatorial fights. Whether we are dealing with a change of heart, political expediency, vacillating moral purpose, or a combination of all three, is impossible to know. But it certainly suggests that it is harder to pin down ancient attitudes to gladiators than is often assumed.

It is out of the question for someone in the early twentyfirst century not to deplore the slaughter of the arena. In antiquity intense enthusiasm for the shows went hand in hand with a whole range of rather different ethical doubts (and snobbish expressions of disdain). Both philosophers and theologians questioned the effect on the audience of watching the bloodshed. Did it, as some argued, damage the capacity for rational thought? What was the effect on the human mind and character? St Augustine writes memorably in his Confessions of one Alypius, who was eventually to become a Christian bishop, going unwillingly to some shows with his friends. Though determined to keep his eyes shut, as soon as he peeped he was hooked. The spectacle had done its work: ‘when he saw the blood, it was as though he had drunk deeply on savage passion’. Others wondered about the moral differences in shows involving different legal categories of victim: killing criminals was one thing, killing Roman citizens quite another. Of course, these are not our own objections; nor, in pagan antiquity at least, do they amount to anything approaching a campaign for the abolition of the shows. That said, they show the Romans thinking rather harder about these spectacles than their popular image would have it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.