Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We have already in this chapter wondered whether the shows in the Colosseum were always quite the extravagant displays that they are painted; whether the roaring crowd did always fill every vacant seat (as the digital technology of Gladiator made it). We end it by wondering whether the crowd – different in their reactions as they must be from us – were quite the conscience-free and murderous enthusiasts for indiscriminate killing that it is convenient for us to imagine. True, in our terms, they were horribly cruel. Their ethical boundaries were drawn in very different places from our own; but that does not mean they had no ethical boundaries, or ethical doubts, at all.

5

BRICKS AND MORTAR

THE ORIGINAL COLOSSEUM?

It is a well-known axiom among archaeologists that the more famous a monument is, the less likely any of its original structures are to survive – the more likely it is to have been restored, rebuilt and, more or less imaginatively, reconstructed. There is an inverse correlation, in other words, between fame and ‘authenticity’ in the strictest sense. The Colosseum is a classic instance of this rule. A large proportion of what you see when you visit is much later than the original work of Vespasian and Titus in the 70s AD. The puzzle of dating the individual parts and the different phases has kept archaeologists amused for centuries. The truth is, though, that – despite the confident assertions of most guidebooks – it is now impossible in many cases to be certain which bits were built when. The usual euphemism that the ‘skeleton’ of the building is still essentially in its original form may be true enough, but it glosses over the question of how much of the building counts as the skeleton.

The monument has suffered all kinds of damage – from fire, earthquake and other natural and man-made disasters – throughout its history. There are records of repairs up to perhaps as late as the early sixth century AD, commemorated in inscriptions that have been discovered in the building (the latest one documents the restoration of ‘the arena and the podium, which had collapsed in an abominable earthquake’). A particularly devastating blaze in 217 is described by Dio, who claims that the ‘hunting theatre was struck by lightning… and such a conflagration followed that the whole of the upper circuit and every thing in the arena was consumed; and then the rest was ravaged by the flames and dismantled’. The building was, according to Dio, out of use for many years. But even with this clear testimony, it has proved difficult to identify exactly the third-century repairs or their extent. The most recent attempt has concluded that the damage was more limited than Dio implies, but at the same time has suggested that one section of the main outer wall of the building, usually taken to be part of the original first-century construction, actually dates from the rebuild in the third century.

The problem is that dating Roman brickwork and masonry is a tricky art. Some Roman bricks were stamped with makers’ marks in the course of their production and these ‘brick-stamps’ can give (or allow one to deduce) an exact date. Yet, even so, it is often hard to tell whether the dated brick is part of a small repair or the main phase of construction – or even whether an old brick has been used to patch up damage centuries later. And not just in the ancient world itself. The Colosseum has continued to be repaired and adapted ever since. Some of this work used material indistinguishable from that used by Romans or, even more often, reused Roman material that was lying about the site. It is now not always possible, even for experts (though few like to admit it), to tell an eighteenth-century insertion from a fourth-century one. Of course, this sense that the monument is a patchwork of many centuries gives it much of its charm. But it also makes it hard to trace the details of its history.

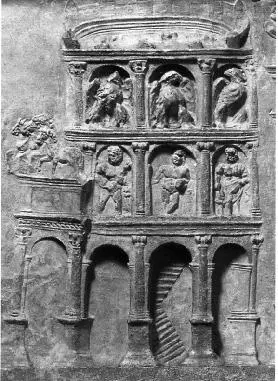

The other main problem in reconstructing the original monument – whether as it stood at its inauguration in AD 80 or at any later period in the Roman empire – is the simple fact that so much of it has disappeared. True, its silhouette remains a magnificent and imposing presence in the Roman city-scape, and it is especially impressive from the air flying into the airport at Ciampino from the north (sit on the righthand side of the plane). But about two-thirds of its ancient fabric has gone, most of that, as we shall see in Chapter 6, rifled in later periods to provide the building material for medieval and renaissance Rome. Large sections of the building as it now stands are not ancient at all, but the result of restoration over the last two centuries. Outside, half the outer wall has been destroyed; inside, there is no arena floor and no seats survive (the small reconstructed section of seating on the north-east side is a fantasy of the 1930s and gives a misleading impression of the original layout – illustration 20). Besides, the stark, almost industrial, character of the monument today is the result of the loss of almost all of its marble facings, its rich paintings and stuccoes, and the statues that once decorated the exterior arches. A relief sculpture of the Colosseum from a first-century Roman tomb gives a quite different, and probably more accurate, impression of the decorative excess of the building in its original state (illustration 21).

Nonetheless, there is still a lot to be learned from a careful look at the surviving remains. The archaeology of the building in some important respects enriches our understanding of what went on there. Equally the accounts of the shows, the gladiators and the animal hunts we have already discussed help to make sense of the tantalising ruin that is the Colosseum today.

THE COLOSSEUM ABOVE GROUND

However confusing it can appear on the site itself, the basic design of the Colosseum is clear enough from the ground plan ( figure 1): a series of concentric circles, leading in from the vast perimeter wall to the space of the arena in the centre. The surviving section of the perimeter wall on the north side (buttressed at each broken end in the nineteenth century) is arranged in four arcaded storeys, each of which corresponds to a floor level on the interior. On the first three storeys are open archways, with half columns in three different orders of architecture, Tuscan on the ground floor, Ionic on the first and Corinthian on the second (a sequence that was admired and often copied in Renaissance buildings). The top storey repeats the Corinthian order, but has small windows rather than open arches. The total height is 48 metres, and in its original extent it is estimated to have used some 100,000 cubic metres of travertine stone, quarried at nearby Tivoli.

At the very highest level of this outer wall are the sockets which were used to attach the awning (the ‘sails’ or ‘ vela ’) that served to keep the sun off the audience. (If you look up from the inside of the building when the sky is bright blue, these sockets are clearly visible.) It used to be thought – and it is still sometimes said – that the five stone bollards which survive on the ground to the east side of the Colosseum, about 18 metres away from the building, were also connected with the awning system: as if part of a series of giant tent pegs that would originally have extended all round the building and have been used to anchor the ropes of the awnings to the ground. Part of a series they almost certainly were, but they would have been disastrously ill-suited to such a weighty task, as they have no foundations and are simply bedded into the soil. A much better guess is that they played some role in a controlling visitors and access to the building.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.