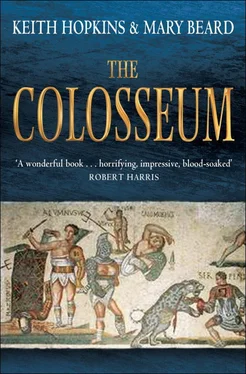

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Working in from the exterior, we find a series of four circular corridors (usually known in studies of this building as ‘annular corridors’ from the Latin for ‘ring’, ‘ anulus ’). These give access to different parts of the monument and to the stairways leading up to higher levels as well as offering amenities such as water fountains and, we must assume, lavatories (though, unlike the fountains, no undisputed remains of lavatories have been discovered). These annular corridors supported the structures above, constructed in a mixture of travertine, other local stone and brick. As the cross-section shows ( figure 3), the number of corridors decreases as you move further up the building.

There were eighty entranceways into the Colosseum from the outside. The four at the main axes were differentiated from the other seventy-six and it is generally assumed (on some – but frankly not very much – evidence) that these were used by the performers and the emperor and his party or by the officials presenting the show. The two on the long axis to east and west are usually taken to be the performers’ entrance and exit (the best argument for this is the adjacent stairs connecting them with the underground service areas of the Colosseum). Modern scholars (and ground plans) often slap technical-sounding Latin names on them: the ‘Porta Libitinensis’ or ‘Libitinaria’, after the goddess of death, Libitina, at the east, through which dead gladiators were removed; the ‘Porta Triumphalis’ at the west, through which the gladiators are supposed to have entered in procession at the start of the show (alternatively it is known as the ‘Porta Sanivivaria’ (‘Gate of Life’) through which the still living gladiators walked out of the arena at the end of their bout). In fact, there is almost no evidence for any of these names, still less that they were regularly applied at the Colosseum. The term ‘Porta Sanivivaria’, for example, is known only from the story of St Perpetua’s martyrdom in Carthage; ‘Porta Libitinensis’ comes from a single puzzling reference in a late biography of Commodus to the emperor’s helmet being twice taken out (it does not say from where) ‘through the Gate of Libitina’.

Of the two entrances on the shorter axis, normally taken to be used by celebrity spectators, only that on the north survives; but the symmetry of the monument would suggest that it was mirrored on the south. There are still traces at the north of a vestibule that would once have protruded out from the line of the main exterior wall. Putting this evidence together with the first-century sculpture of the Colosseum (illustration 21) and with images on coins allows us to reconstruct a monumental entranceway on each side, topped by a four-horse chariot presumably carrying the emperor. If the Colosseum were one of the key contexts in the city of Rome for the display of the emperor, imperial statues would have been a particularly resonant and appropriate image over these two principal entrances.

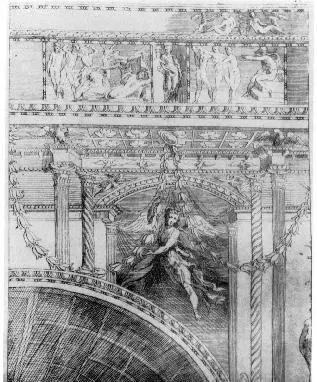

Even more striking is the evidence we have for the stucco decoration at the north entrance. Although only a very few fragments are still visible, when they were much better preserved these stuccoes were drawn by Renaissance artists (including Giovanni da Udine, a pupil of Raphael, who based some of his designs for the Villa Madama on them). The exact interpretation of these is not made easier by the fact that different artists depict them rather differently – divergences that may themselves suggest that the stuccoes were not as well preserved in the Renaissance as they appear, or at least that a degree of imagination has gone into these apparently antiquarian documents. Nor is the date certain: perhaps part of the original first-century decoration, more likely part of a later makeover. But whatever they represent and of whatever date, they are precious evidence for the lavish decoration of the building that has now almost entirely disappeared. Other fragments of brightly painted plaster survive from the corridors, on the basis of which it has been tentatively suggested that vivid colours were widely used in the building’s early phases, toned down to something rather less flashy later.

The main principles of the original seating plan are, as we have seen, clear enough: the seats were ranked hierarchically from the ringside to the top of the house. We can also trace on the ground plan the routes that must have led to the different areas of the auditorium ( figure 1): senators, for example, would have entered and made straight for the seats on the podium at the front (Route A, and repeated round the building); those sitting at the highest level would have made straight for the stairs (Route B, repeated), without any opportunity to mingle with the aristocrats, and would then have emerged through a balustraded opening into their designated block (some of the late decorations of these balustrades survive). On the other hand, reconstructed cross-sections of the building (like our figure 3), which confidently mark the exact position of the seats and the number of rows, are based on much less firm information than their clear lines would suggest. The simple reason for this is that no seating survives and so all reconstructions are based on a more or less rough guess of what would fit on the skeleton that remains. This problem is especially acute in the elite sections of the building. The podium on which the (movable) senatorial seats rested certainly extended further down than what now appears, to a casual observer, to be the boundary wall of the arena. This is in fact the back wall of a tunnel which carried at least part of the elite seating above it (illustration 20 and figure 3) and probably acted as a service tunnel around the arena’s edge – with openings through its now largely destroyed front wall onto the arena itself. But the exact extent of the senatorial area is uncertain, as is its form: it is sometimes reconstructed as a sloping area, sometimes as stepped. All these uncertainties make an accurate estimate of how many people it could accommodate ( p. 111) very difficult.

The most elite seating of all was in the boxes that we assume took pride of place on the north and south sides of the arena, and are regularly illustrated in imaginative versions of the Colosseum from Gérôme to Ridley Scott and beyond (illustration 8, p. 57). Nothing remains of these, but they must have been located at the ringside, approached by the elaborate entranceways at north and south. There is strong evidence to connect the position at the centre of the southern side with the emperor himself, for an underground passageway has been discovered which gave access to the ringside at this key point from somewhere outside the building to the east. About 40 metres of it has been excavated but the starting point has not been identified (figure 1). What is clear, however, is that it was an insertion (possibly under the emperor Domitian soon after the building was opened) into the original structure and that it was elaborately and richly decorated. The walls were originally faced in marble or alabaster, later replaced with frescoed plaster; there was lavish stucco on the vault and in niches; the floor was covered in mosaic. It seems very likely indeed that this passageway gave the emperor private access to his box, in addition to the main entranceway on the ground floor. In fact, its popular name is now ‘the passageway of Commodus’, so called after a story in Dio that Commodus was once attacked by a conspirator ‘in a narrow entrance way’ in the Colosseum – a nice illustration of the emperor’s vulnerability even (or especially) here. If the connection is right, he would have been attacked in his own private corridor, leading to his own ceremonial seat.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.