Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

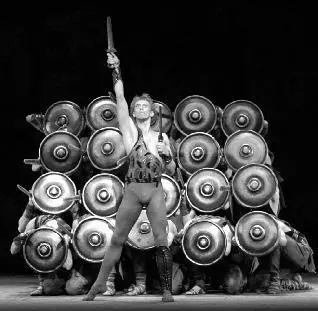

The strongest image of the gladiator in Roman culture, however, was as a virile sex-symbol. Graffiti from Pompeii, probably written by the gladiators themselves (and so a boast as much as a comment), call a Thracian by the name of Celadus (or ‘Crowd’s Roar’) ‘the heart-throb of the girls’ and his partner Cresces (perhaps ‘Bigman’, a retiarius ) ‘lord of the dolls’. It was in fact a standing joke at Rome that women were liable to fall for the heroes of the arena. The satirist Juvenal, writing around AD 100, famously turned his wit on a senator’s wife, Eppia, who had apparently run off with a sexy thug from the Colosseum:

What was the youthful charm that so fired Eppia? What

was it hooked her? What did she see in him that was worth

being mocked as a fighter’s moll? For her poppet,

her Sergius

was no chicken, forty at least, with one dud arm that

held promise

of early retirement. Deformities marred his features –

a helmet-scar, a great wen on his nose, an unpleasant

discharge from one constantly weeping eye. What of it?

He was a gladiator. That makes anyone an Adonis;

that was what she chose over children, country, sister,

and husband: steel’s what they crave.

The joke here is, of course, on the woman, satirised for an insatiable sex-drive that leads her to abandon everything for this brute. This is Roman misogyny speaking loud and clear. But the last line of this extract hints at a telling pun. ‘Steel’s what they crave’. The Latin is ‘ ferrum ’ – literally ‘iron’, or ‘sword’. Another common Latin term for sword (and one embedded in the word ‘gladiator’ itself) was ‘ gladius ’ – which was also Latin street-talk for ‘penis’. The point about the gladiator is that he was, for better or worse, as one modern historian has aptly put it, ‘all sword’.

Juvenal is satiric fantasy. But similar stories, true or not, were told of historical figures too. The empress Faustina, for example, wife of the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius and mother of the notorious Commodus, was rumoured to have conceived Commodus during an affair with a gladiator. One particularly lurid ancient account claims that when she confessed this passion to her husband, he consulted soothsayers who recommended that he have the gladiator killed; after this he was to make his wife bathe in the dead man’s blood and then have sex with her. The story goes that he followed these recommendations, and then brought Commodus up as his own son. Historians have, understandably, been dubious about this tale, and guess that it was invented to provide a convenient explanation for Commodus’ obsessive enthusiasm for the arena.

A notorious find from Pompeii is often seen as positive confirmation of the fondness of upper-class Roman women for rough gladiatorial trade. In the excavations of the gladiators’ barracks, the skeleton of a heavily jewelled lady came to light – presumably, it has often been suggested, caught in the act with her paramour, trapped for eternity (as every adulterer’s nightmare must be) in the wrong place at the wrong time. If so, she was taking part in a very squashed session of group sex. For in this tiny room were found not only the rich lady plus partner, but no fewer than eighteen other bodies, children included, plus a variety of bric-à-brac, chests with fine cloth and so forth. Much more likely we have the remains of a group of people fleeing the city with their prize possessions who had taken refuge in the barracks when the ash and pumice rained too hard, never to re-emerge. But if this turns out to have been no adulterous tryst after all, it is still the case that in the Roman imagination the gladiator was a figure of larger-than-life sexual power.

How then do we account for these conflicting images? How do we explain why a figure of such social and political stigma was also the object of admiration and fantasy? All kinds of ideas have been canvassed. In part we are no doubt dealing with a common fascination of elite culture for its opposite: a combination of nostalgie de la boue and Marie Antoinette playing at milkmaids (or, for that matter, female members of the British royal family cavorting around London clubs dressed up as policemen). In other words, gladiators were not sexy and exciting despite being beyond the social pale, but because they were. Maybe also, in a highly militaristic culture such as Rome, gladiatorial combat played a special role. Whether the Romans were engaged in active military combat or not (and long before the first century AD fighting normally took place miles from the centre on the remote frontiers), the lust for battle was replayed in – or displaced into – the arena, and military prowess found its expression in the skill of the gladiators; this could not simply be abominated. Even more important, though, must have been the power of the spectacle itself. To be the centre of attention of a vast crowd is always empowering. Hence, for example, the almost heroic status of the condemned criminal in early modern Britain giving his gallows speech in front of those assembled to watch his hanging; and hence, in part at least, the celebrity of modern football stars. To be watched by tens of thousands of people in the Colosseum, to have all eyes on you, transcended the invisibility of social disadvantage. Emperors realised this as well as anyone: when they left the imperial box to take their place in the arena, it was partly a gambit to recapture the gaze of the crowd. The emperor always risked being upstaged by the abominated creatures whom everyone was watching.

Yet there was more to the allure of the gladiator than the familiarising image of the modern footballer might suggest. The gladiator was a crucial cultural symbol at Rome because he prompted thought, debate and negotiation about Roman values themselves. Of course, there is something tautological about that claim: all crucial cultural symbols prompt negotiation about their society’s values; that’s what makes them ‘crucial cultural symbols’ in the first place. Nonetheless, gladiators and gladiatorial combat do focus attention on many of the ‘jagged edges’ of Roman culture: on the question of what bravery and manliness consist in; on power and sexuality; on proper control of the body; on violence and death and how to face it. Their position in Roman society, and in the Roman imagination, was bound to be contested and ambivalent.

Or so it must have been from the point of view of the audience, and of those Romans who quaffed their wine from gladiator glasses, or sealed their letters with a gladiator signet-ring. What we are missing (apart from some blokeish boasting on the part of Celadus and Cresces and the occasional ghoulish bon mot on a tombstone) is the point of view of the gladiators themselves. There is no account from any arena fighter of what it felt like on the other side of the barrier that separated the spectators from the slaughter. The hints we get, however, suggest terror was as powerful a feature as heroism. This is presumably the message of Symmachus’ twenty-nine Saxons who pre-empted the agony and humiliation of the performance by strangling each other. Even this is rather upstaged by a tale told by Seneca of another arena performer, an animal hunter, not technically a gladiator. The man, a German by birth, went off to the lavatory just before the show (‘the only thing he was allowed to do without surveillance’); there he grabbed the stick with a sponge on the end (which was the Roman equivalent of lavatory paper) and rammed it down his own throat, suffocating to death. Seneca treats this as an instance of consummate courage (‘What a brave man! How worthy of being allowed to choose his own death!’). We might detect desperation and terror, as well as bravery.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.