Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

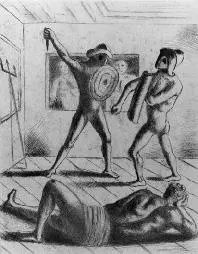

Some archaeologists, predictably, have tried very hard to resist that suspicion, and have resorted to some desperate arguments in the process. Maybe this Pompeian armour was a new consignment, not yet knocked around in the arena. Maybe the short length of the gladiatorial bouts meant that such weight of equipment was manageable for these fit men; it was not, after all, like fighting a day-long legionary battle. Maybe – and this is where desperation passes the bounds of plausibility – the helmets were known to be so strong that no canny opponent would have bothered to take aim at them, hence their apparently pristine state. Maybe. But much more likely is that this armour was the display collection, used only perhaps when the gladiators paraded into the arena at the start of the show (to be replaced by more practical equipment as soon as the fighting started), or on other ceremonial occasions. It was the also the kind of equipment that would best symbolise the gladiator on funeral images or other works of art. Our guess is that what the spectator would actually have seen in the Colosseum or any amphitheatre was probably much less like the figure re-invented by Gérôme (who almost certainly had seen the Pompeian finds), and much more like the more lightly clad, though still recognisably ‘gladiatorial’, gladiators envisaged by de Chirico in the 1920s and the rather more nifty fighters depicted in the casual graffiti from Pompeii (illustrations 13 and 14). There is little reason to think that the gladiators regularly lumbered around the arena in their display kit (which would certainly have allowed no Russell Crowe-style balletics). Perhaps no more reason than to imagine that British university students regularly wear on campus the mortar boards, gowns and imitation fur in which they are dressed for those ceremonial graduation photographs, treasured in their parents’ photo albums.

But what, finally, of the standard programme of displays in the amphitheatre: animal hunts in the morning, executions at midday, gladiators in the afternoon (with the public gladiatorial dinner the evening before to allow the punters to study form)? It is quite true that each of these elements is referred to by ancient writers describing the shows. The question is whether or not it is right to stitch all these references together into a ‘programme’. This is a trap modern students of Roman culture often fall into: pick up one reference in a letter written in the first century AD, combine it with a casual aside in a historian writing a hundred years later, a joke by a Roman satirist which seems to be referring to the same phenomenon, plus a head-on attack composed by a Christian propagandist in North Africa; add it all together and – hey, presto! – you’ve made a picture, reconstructed an institution of ancient Rome. It is exactly this kind of historical procedure which lies behind modern views of what happened at a Roman bath or at the races in the Circus Maximus, or at almost any Roman religious ritual you care to name. And it lies behind most attempts to reconstruct the shows in the amphitheatre too.

Why is it usually assumed that the lunch interlude was the time for executions? Because the philosopher Seneca writing in the mid first century AD, before the Colosseum was built, in a letter concerned with the moral dangers of crowds, complains that the midday spectacles in some shows he had attended were even worse than the morning. ‘In the morning men were thrown to lions and bears, at noon to the audience,’ he quips. And he goes on to deplore the unadulterated cruelty, while explaining that its victims are criminals – robbers and murderers. That is the only evidence for the lunchtime executions (apart perhaps from a passing reference to ‘the ludicrous cruelties of midday’ in Tertullian’s Christian attack on Roman spectacles). In fact, there is just as much evidence for some kind of burlesque or comedy interlude at lunchtime. And that may have been what Seneca was expecting, when he writes that he was hoping for some ‘wit and humour’.

Why is it believed that gladiators regularly had a public meal the night before their show? Because a couple of Christian martyrs in the arena at Carthage in AD 203 were given ‘a last supper which is called a “free supper”’; because Tertullian again, rather puzzlingly, claims that he himself does not recline in public ‘like beast fighters taking their last meal’; and because Plutarch writing at the turn of the first and second centuries AD claims that although gladiators are offered expensive food before their shows, they are more interested (understandably we might think) in making arrangements for their wives and slaves. Maybe that is enough evidence to suggest a regular public, pre-show banquet; maybe not. There is certainly no evidence at all for the punters coming along to study form; in fact, we have no direct evidence at all for widespread betting on the results of this fighting. That is an idea that comes mostly from the imagination of modern historians, trying to make sense of the shows by assimilating them to horse racing, or to ancient chariot racing, which certainly did attract gambling.

Of course, the success of public spectacle depends, in part, on the audience having a general idea of what is going to happen. In that sense there must have been some shared foreknowledge of what was likely to be involved in shows in the amphitheatre: animal hunts, executions, gladiators, plus (on a very lucky day) more adventurous displays such as those mock naval battles. Certainly there is a quite a lot of evidence for the animal hunts often being scheduled in the morning (it might have been easier to keep the gladiators hanging around than the animals); and casual references to ‘the morning shows’ do usually seem to refer to the hunts and other animal displays. But success also depends on novelty and surprise. We must reckon that, rather than the rigid order of ceremonies often assumed, the performances at the Colosseum varied enormously according to the ingenuity of the presenter, the amount of money at his disposal, the practical availability of beasts, criminals or gladiators. After all, a hundred days of spectacles with executions each lunchtime would surely have soon exhausted the supply of condemned men and women, even in a society as brutal and cruel as Rome. These games must have been the same and different each time.

The Colosseum and its shows are the most familiar part of ancient Roman culture in the modern world. Films and novels, as well as serious scholarly accounts, present to us a relatively consistent picture of the performances in the amphitheatres. At the same time as we puzzle at the cruelty and the bloodshed involved, at why they did it, we feel relatively confident that we know roughly what it was they did. Most readers will be able to close their eyes and conjure an image of the Colosseum in full swing. That is why it is such an important monument in the history of modern engagement with ancient Rome. This chapter has tried to suggest that some of that confidence is ill placed. It is much harder than we often imagine accurately to recreate the scene in the killing fields of the Colosseum; still harder (as the extraordinary series of poems by Martial prompts us to reflect) even to begin to understand what it was the Romans themselves saw in this slaughter.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.