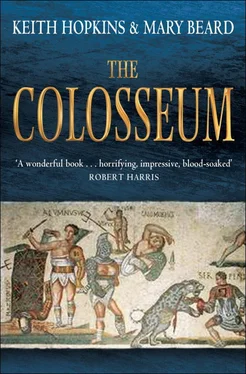

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But happily, looking closer at the Colosseum is not only a matter of discovering that we know less than we thought. The next chapter will turn a shrewd eye towards some of the Colosseum’s cast of characters: from the gladiators again, through the lions to the emperor and audience, and to what we can tell of their reactions to what they witnessed. Of course, these were only part of the cast list. Apart from a handful of references on tombstones and other inscriptions to slaves and ex-slaves who looked after the costumes or guarded the gladiators’ weapon store, the vast slave battalions who serviced the building and its entertainments, the cleaners and gate-keepers, the wardrobe-mistresses and the odd-job men, are now completely (in the old catch-phrase) ‘hidden from history’. Nonetheless, if we change the focus of inquiry slightly and ask rather different questions of the evidence we have, we discover that we know more than we thought rather than less.

4

THE PEOPLE OF THE COLOSSEUM

‘HEART-THROBS OF THE GIRLS’?

Gladiators were marginal outsiders in Roman society. Some of them literally so: captives of war, the poor and destitute who saw in possible success in the arena their only (desperate) hope, slaves sold to the gladiatorial ‘training camps’ (in Latin ludi , usually rather too domestically translated as ‘schools’), condemned men sent there as punishment. They were, in fact, almost exclusively men. Apart from a few exceptional and usually scandalous cases – such as the emperor Nero’s reputed display of an entirely black troupe of gladiators, women and children included – female gladiators are more a feature of modern over-optimistic fantasy than Roman practice. The body of a Roman woman found in London in 2000 and eagerly identified as a female gladiator, on the basis of some lamps found with her carrying gladiatorial scenes, was probably nothing of the kind but just an ‘ordinary’ woman buried with her favourite trinkets, if anything a fan rather than a contestant.

A gladiator’s life was dangerous, painful and probably short – even if for the skilled or lucky few success might bring rewards and eventually discharge. It is significant that the most famous doctor of the Roman world, Galen, who ended up as the court physician to the second-century emperor Marcus Aurelius, started his career treating gladiators in Pergamum (in modern Turkey). He claims to have found the experience useful in his studies of human anatomy and various therapeutic methods and regimes, and he drew on it in writing his voluminous medical treatises. When we read his account of the problems of replacing intestines hanging out through a gaping wound, we are probably getting close to some of the real-life gladiatorial experience in the arena. The simple presence of a doctor, however, hints at the economic interests that may have mitigated the physical conditions experienced by most of the fighters. A dead gladiator was an expensive gladiator. Likewise mangy specimens were probably no crowd-pullers. Their living quarters, clothing and rations must have varied enormously through the many different troupes and camps in the empire: some were small private-enterprise affairs (much like that of the gladiatorial impresario Proximo, played by Oliver Reed, in Gladiator ); others were effectively part of the imperial state organisation in Rome itself, located conveniently close to the Colosseum. But, wherever they were based, logic suggests that they would not have been kept in starvation. Some Roman writers refer to standard gladiatorial fare as ‘ sagina ’, ‘stuffing’ – a characteristically snobbish disdain for humble food, and at the same time hinting unpleasantly at the similarity of the fighters to dead animals. But coarse diet or not, it would probably have been eyed enviously by large sections of the Roman poor.

Beyond the physical dangers they faced, gladiators were marginalised in a civic and political sense. Many were of slave status anyway, which meant that they had only the most limited legal and personal rights. But even those who were by origin freeborn Roman citizens suffered a whole series of penalties and stigmas when they became gladiators, which in many respects amounted to losing their status as full citizens. It involved much the same ‘official disgrace’ (‘ infamia ’ in Latin) as prostitutes and actors suffered by virtue of their profession. We know of Roman legislation from the first century BC that prevented anyone who had ever been a gladiator from holding political office in local government; they were also not allowed to serve on juries or become soldiers. Even more fundamentally they seem to have lost that crucial privilege of Roman citizenship: freedom from bodily assault or corporal punishment. Roman civic status was written on the body. Part of the definition of a slave was that, unlike a free citizen, his body in a sense no longer belonged to him; it was for the use and pleasure of whoever owned it (and him). A gladiator fell into that category, as the notorious oath said to have been sworn by recruits when they entered the gladiatorial camps proclaimed. Its terms no doubt varied from place to place, but Seneca quotes a version that has a gladiator agreeing on oath ‘to be burnt, to be chained up, to be killed’. Such a promise of bodily submission was completely incompatible with what made a free Roman citizen free.

It is hardly surprising then that gladiators are often treated as the lowest of the low in Roman literature, and symbols of moral degradation. Not for ancient Rome the modern political heroisation of Spartacus, the first-century BC gladiator who led a, temporarily successful, rebellion of slaves against their Roman oppressors and has starred in countless modern novels, movies, ballets, operas and musicals – including in 2004 a French blockbuster show Spartacus le Gladiateur , who ‘dreamed of being free’. By contrast, Roman politicians looking for a slur to cast on their rivals would often reach for the term ‘gladiator’. And Seneca again, when writing a rather pompous philosophical essay in the form of a letter of condolence to a man who had just lost his young son, attempts to cheer him up by reminding him of the boy’s uncertain and possibly ghastly future: he might have squandered his wealth and ended up as a gladiator. It is hardly surprising too that we know of repeated attempts by the Roman authorities legally to prohibit senators from fighting as gladiators in the arena.

But this prohibition should give pause for thought. For if the gladiators were so completely despised and abominated, why on earth would legislation have been necessary to prevent senators from joining them? One answer is that these regulations were more symbolic than practical. The function of law is often to proclaim the importance of boundaries, rather than literally to prevent people crossing them. The reason most of us do not commit incest is not, after all, that there is a law against it. Here we might be seeing another instance of Roman insistence that there was a firm line to be drawn between fighters in the arena and civilised (especially elite) Roman society.

There is, however, plenty of evidence to suggest that gladiators were as much admired and celebrated as they were abominated. Far from just flirting with the idea of gladiatorial combat, some members of the Roman elite did enter the arena; even some emperors (admittedly ‘bad’ ones) left the imperial box in the Colosseum and joined in the fight – as we shall see later in this chapter. The admiration of the gladiators took a variety of forms. While philosophers such as Seneca might with one breath deplore the degradation of the gladiators or their corrupting effect on the crowd, with the next they were seeing in the arena an example of true courage, of a ‘philosophical’ approach to death, even a model for how the truly wise man should act. More generally Roman households seem to have been littered with images of gladiators, combat and equipment. The lamps with gladiatorial decoration buried alongside the woman from Roman London are only one example among thousands upon thousands of such objects, from the elegant to the kitsch: not just the expensive mosaic floors or paintings with scenes of the arena (though there are plenty enough of them decorating up-market houses all over the empire), but ivory knifehandles carved as gladiators, lamps moulded in the shape of gladiatorial helmets, even, from Pompeii, a baby’s bottle with the image of a gladiator in full fight. And this is not to mention the signet rings, the glass beakers, the tombs, marble coffins, water flasks, candlesticks – all displaying characters from the arena. How any of this relates to the odd custom of Roman brides parting their hair with a spear that had been dipped into the blood of a dead gladiator is frankly a mystery. It may anyway have been more a piece of antiquarian folklore than a regular practice, as puzzling and quaint to the Romans as it is to us. One of the Roman scholars who did puzzle over it came up with various possible explanations. Perhaps the union of the spear with the gladiator’s body symbolised the bodily union of husband and wife. Perhaps it was supposed to help her chances of bearing brave children. Who knows?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.