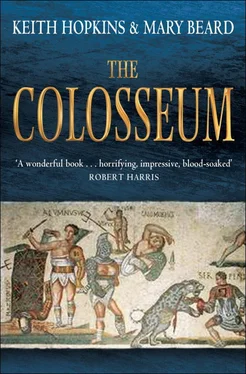

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The same dilemma confronts us when we come to ask how often the Colosseum was in use. For Trajan’s celebrations of his Dacian victory through 108–9, it was apparently hosting performances almost one day out of five. But what was ‘normal’? No one knows. Strikingly few days, though, are assigned to ‘regular’ gladiatorial games in any of the Roman calendars that have been preserved: in the fourth century AD it seems that, out of 176 days of ‘holiday’, just over a hundred were devoted to theatrical shows, sixty-four to horse and chariot racing and only ten days to gladiatorial games. Are we to imagine that, outside special occasions, the Colosseum would have been mothballed? Or that it would have been a constant bustle of workmen and administrators clearing up the mess, getting ready for the next show and doing running repairs on the fabric and machinery? Or that, for much of the year, it provided a convenient home for all kinds of other activities that readily colonised its city-centre location, a place to flog your wares, take a nap, sight-see or make a pick-up? Again, no one knows. But when we reflect on the significance of the shows that took place in the Colosseum, it is worth remembering that, as with Christmas, sheer frequency is not necessarily a good guide to cultural importance.

‘HAIL CAESAR. THOSE ABOUT TO DIE SALUTE YOU’?

To read most modern accounts of the shows in the Colosseum (or indeed of those, admittedly smaller-scale, displays in amphitheatres all over the Roman empire) you would think that a handbook to such events survived from the ancient world – or at the very least a series of programmes, laying out in detail the order of ceremonies according to a standard pattern. We are repeatedly told that the sequence of the day’s events in the arena was fixed by rule or custom. In the morning were the wild animal hunts: more or less exotic species (and the more exotic the better, of course) put to fight each other or pitted against trained marksmen and hunters, some on horseback, others on foot, picking the animals off with spear, sword or arrow. In the ‘lunch break’ came the public executions, either in the ‘mythological’ form that Martial evokes, or in other varieties of ingenious slaughter and torture (including the notorious lions), or just plain killing.

It was not until the afternoon, so it was said, that the gladiatorial bouts proper began. The fighters entered, hailed the emperor with the famous words ‘Those about to die salute you’ and the real fun started. They sported different types of armour and weaponry, and had adopted a range of fighting styles: there were ‘net-men’, for example, heavy-armed ‘Thracians’ and ‘Samnites’, and murmillones or ‘fish-heads’ (so called after the emblem on their helmets). Although all kinds of formation were possible, they usually fought in pairs, one to one, trainers and umpires on hand to supervise the carnage, stretcher bearers (dressed as gods of the Underworld) to carry out the dead and wounded, as well as a blacksmith and forge for instant repairs. The victors may have been handsomely rewarded with popular fame, lavish presents from the sponsor of the show and ultimately (as was the fate of Priscus and Verus) with an honourable discharge. A wounded or defeated gladiator, on the other hand, was at the mercy of the audience. He would hold up his little finger as a sign of surrender, at which point the crowd would roar their preference for killing or sparing, putting their thumbs up or down. Many of the onlookers probably had a vested interest in the outcome and a small fortune staked on individual fighters (in fact the night before the show, the gladiators had their last meal in public , which gave aficionados a chance to study their form before placing their bets). But it was finally up to the sponsor to decide whether to spare the man’s life or have him killed.

This is the scene captured in perhaps the most evocative modern painting of the Colosseum’s arena (illustration 8). Jean-Léon Gérôme’s canvas, painted in the early 1870s, shows a victorious combatant standing triumphant over a ‘net-man’ (or retiarius ; his trademark net and trident have fallen to his right), who seems to have collapsed over a fighter dead or injured from a previous bout, but not yet cleared out of the arena. The victor wears one of those elaborate helmets distinctive of several types of gladiator, here decorated with a fish – though it is hard to pick out except on the original (now in Phoenix, Arizona) or on very large-scale reproductions. He is meant to be a murmillo . Equally distinctively, he displays a large amount of naked flesh. For one striking feature of Roman gladiatorial combat, compared with medieval jousting and knights all protected in their chain mail, was the exposure of so much of the bare body; it is as if they had to be visibly vulnerable. We are witnessing here those tense few moments while the winner waits for a sign from the emperor, seen sitting in his imperial box in the carefully reconstructed Colosseum. Kill or not? But our attention is drawn to the women on the front row (presumably the Vestal Virgins, the priestesses who were, as we shall see in Chapter 4, the only women allowed to watch from these ringside seats). With disconcerting eagerness they are signalling their desire for the kill, thumbs down. In fact, the title of the painting is the Latin phrase ‘ Pollice Verso ’, literally ‘Thumbs turned’ – the phrase used by Roman writers to indicate the vote for a kill. Despite modern scholars’ often confident claims to the contrary, we do not actually know in which direction Romans ‘turned their thumbs’. It may have been ‘up’ for death and ‘down’ for mercy; or, as Gérôme imagines it, vice versa.

This is the painting that is supposed to have inspired the director of Gladiator , Ridley Scott: ‘That image spoke to me of the Roman Empire in all its glory and wickedness,’ he is quoted as saying. ‘I knew right then and there I was hooked.’ It also forms a sequel to another painting of Gérôme’s, finished a decade or so earlier in 1859. In this other canvas (which has ended up in Yale University Art Gallery) we see a small posse of gladiators who have just entered the Colosseum’s arena – obviously not the first fighters of the day, to judge from the corpse past which they have just had to walk. They raise their arms to acknowledge the emperor. The title of the painting, again in Latin, is that famous phrase: ‘ Ave Caesar. Morituri te salutant! ’ ‘Hail Caesar. Those about to die salute you!’

Sadly, there is no evidence at all that this phrase was ever uttered in the Colosseum, still less that it was the regular salute given by gladiators to the emperor. Ancient writers, in fact, quote it in relation to one specific spectacle only, and not a gladiatorial one. According to the biographer Suetonius – and Dio has much the same story – it was the phrase used by the ‘naval fighters’ (‘ naumacharii ’; condemned criminals according to the historian Tacitus) in a spectacular mock battle on the Fucine Lake in the hills east of Rome, put on in AD 52 by the emperor Claudius, just before his almost equally spectacular feat of draining the lake. The story was that when the emperor heard the word ‘ morituri ’ (‘those who are about to die’) he made a feeble joke by muttering ‘or not, as the case may be’. Somehow the naumacharii picked this up and, taking it as a pardon, refused to fight. The emperor was forced to hobble off his throne and persuade the men back to the fight. This frankly implausible tale (how on earth were the fighters on the lake supposed to have heard the words muttered from the safe distance of the imperial throne?) is the only reference we have to the words which have become the slogan of gladiatorial combat in general, and of the Colosseum in particular, in modern culture (illustration 9).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.