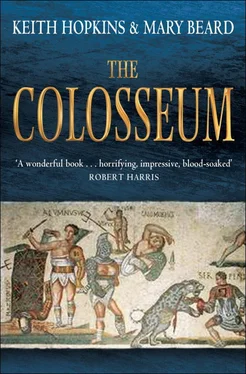

Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Keith Hopkins - The Colosseum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Profile Books, Жанр: История, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Colosseum

- Автор:

- Издательство:Profile Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:9781846684708

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Colosseum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Colosseum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Colosseum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Colosseum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

By the time the Colosseum was inaugurated in AD 80, monarchy was so firmly entrenched that emperors could readily risk, even periodically enjoy, confronting their citizen-subjects collectively. More than that, it was essential to their power-base that they should see, and – even more crucially – be seen by, the people at large. Whatever the harsher realities, there was always the ideal or myth that citizens had the right of access to the emperor, to ask a favour, to correct an injustice, to hand in a petition. One illusion on which the Roman monarchy was founded was that the emperor was only the first aristocrat among equals, and one of the emperor’s titles right from the beginning cast him in the role of Tribune (or Protector) of the People. No other ancient monarchy, whether in Persia, Egypt, India or China, ever staged such regular meetings between ruler and subjects. In fact, an ancient Chinese visitor to the Roman empire thought the public accessibility of the emperor quite extraordinary: ‘When the king goes out he usually gets one of his suite to follow him with a leather bag, into which petitioners throw a statement of their case; on arrival at the palace, the king examines the merits of each case.’

Of course, the Roman people had their fond illusions too: they thought that they could, occasionally at least, collectively influence what the emperor did by letting their rhythmically chanted views be heard.

There were other locations, to be sure, where the emperor could confront his people: in the Forum, for example, or in the Circus Maximus. But the Forum was small by comparison, and the Circus was if anything too huge to concentrate the popular voice. The Colosseum was a brilliantly constructed and enclosed world, which packed emperor, elite and subjects together, like sardines in a tin. Its steeply serried ranks of spectator-participants, watching and being watched, hierarchically ordered by status (by rule, the higher ranks sat near the front, the masses at the back), faced each other across the arena in the round. It was a magnificent setting for a ruler to parade his power before his citizen-subjects; and for those subjects to show – or at least fantasise about showing – their collective muscle in front of the emperor.

The Colosseum was very much more than a sports venue. It was a political theatre in which each stratum of Roman society played out its role (ideally at least; there were times, as we shall see in Chapter 4, that this – like all political theatre – went horribly and subversively wrong). The emperor knew he was emperor best when cheered by the ovations of an enthusiastic crowd who were seduced by the prospect of violent death (whether of animals or humans), by the gifts the emperor would occasionally have showered amongst the spectators and by the sheer excitement of being there. The Roman elite in the front seats would have paraded their status, nodding to their friends: this surely was where business contracts, promotion, alliances, marriages were first mentioned or followed up. The crowd, usually grateful and compliant, sometimes chanted for the end of a war or for more shows – seeing their power as the Roman people all round the arena. It was a vital part of Roman political life to be there, to be seen to be there and to watch the others. Hence the building’s iconic status for the Romans, as well as for us.

3

THE KILLING FIELDS

AD 80: OPENING EVENTS

The Colosseum was officially opened under the new emperor Titus in AD 80, in an extravaganza of fighting, beast hunts and bloodshed that is said to have lasted a hundred days. The scale of the slaughter is hard to estimate. We have no figures at all for deaths among the gladiators, but Titus’ biographer, Suetonius, claims that during these celebrations (though not necessarily in the Colosseum itself) ‘on a single day’ 5000 animals were killed – a claim that has been boldly re-interpreted by a few modern scholars to mean ‘on every single day’ of the performance, so giving a vast, and frankly implausible, total of half a million animal casualties. One of the fullest accounts of the proceedings, by the historian Dio writing in the third century, is rather more modest in its estimates: he reckons that 9000 animals were slain in all. But elsewhere, discussing games given by Julius Caesar in 46 BC, Dio reflects on the difficulty of calculating the correct tally of fighters or victims. ‘If anyone wanted to record their number,’ he complains, ‘they would have trouble finding out and it would not necessarily be an accurate account. For all things of this sort get exaggerated and hyped.’ The Roman audience’s appetite for slaughter was presumably well matched by the capacity for boasting on the part of those who put on the shows.

Many of the practical arrangements are also tricky to reconstruct. One question that has puzzled archaeologists and historians for centuries is whether or not the central arena was flooded during these opening games. Dio writes confidently of how ‘Titus suddenly filled the arena with water and brought in horses and bulls and other domesticated animals which had been taught to swim’ (if ‘swimming’ is what Dio means when he says, literally, ‘had been taught to behave in liquid just as they did on dry land’). And he goes on to describe Titus producing ships and staging a mock seabattle, apparently recreating one of the famous naval encounters of fifth-century BC Greece, between the forces of the cities of Corcyra and Corinth. This extraordinary spectacle would certainly not be possible in the building as it survives today, for there is no way that the basement of the arena (with its intricate set of lifts and other contraptions for hoisting animals) could be waterproofed. Maybe when the amphitheatre was first built, before the insertion of all that clever machinery, it had ingeniously allowed for the option of flooding. Or maybe Dio was mistaken. Suetonius, in his account, certainly suggests that the water displays took place in a quite different purpose-built location. Even Dio himself, in describing the spectacles that must have spread widely over the city during the hundred days, has some of the water sports – including another mock naval battle, this time apparently involving 3000 men – staged in a special facility constructed by the first emperor Augustus.

Whether or not the Colosseum was miraculously converted back into a lake (which would have been a neat joke on Nero’s private lake that the public amphitheatre had replaced), the range of displays put on for the building’s inauguration were the most lavish that Roman money and imperial power could buy. Dio again refers tantalisingly to fights staged between elephants and between cranes – though exactly how they made these birds fight each other is hard (or awful) to imagine. He also mentions that women were involved in the wild beast hunts, while being at pains to reassure us that these were not women ‘of social distinction’. But the most vivid recreations of these spectacular events are found in Martial’s book of poems ( The Book of the Shows ) which was written to commemorate the opening of the amphitheatre. Exaggerated flattery of his imperial patron Titus, these verses may have been. There is no doubt a good deal of wishful thinking and poetic licence in the details of the spectacles described. Nonetheless, this book is one of the very rare cases where we can bring together a work of ancient literature, a specific ancient building and what happened in it on one particular occasion. The poems help us to glimpse not only what might have taken place there, but what a sophisticated Roman audience might have found to admire in these horrible, bloodthirsty performances. They bring us face to face with the (in Roman terms) exquisite inventiveness of cruelty.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Colosseum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Colosseum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Colosseum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.