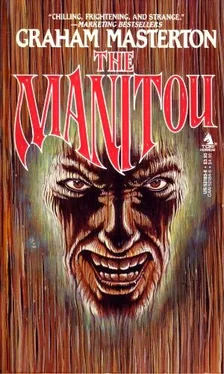

In 1975, Graham Masterton wrote THE MANITOU, the story of a Native American who returns from the dead. After selling over a million copies, THE MANITOU was made into a movie, which had the honor of being the first Western horror novel published in Poland during its post-Communist era.

Born in 1946 in Edinburgh, Scotland, Masterton has participated in journalist, edited a magazine, and written over 75 books including many "how-to" books dealing with sexual topics. Masterton and his wife, Wiescka, currently live in Cork, Ireland with their three sons.

Introduction

by

Bernhardt J. Hurwood

Ordinarily readers of fiction do not find introductions when they settle down with what they are expecting to be a good book — especially when it comes to novels of spine-chilling suspense. But then, The Manitou is no ordinary novel.

In case you don't know what a Manitou is, I have no intention of diminishing the plot's shock value; you will find out soon enough. Let it suffice for me to say, as one who has had considerable experience exploring the darker side of the supernatural, that you are in for a fair share of shudders and chills as you plunge into the tale that lies ahead.

If you have any qualms about the unknown, about unlocking doors that unleash terrors which might creep against your will into your nightmares, then put this book down and rush out into the sunshine. Now! Like some mind-gripping drug, it has the uncanny ability to seize you and hold you firmly in its clutches from the moment you begin until you drop the book from your trembling fingers after you have finally finished the last page.

When a charming, witty, and sophisticated fellow like author Graham Masterton succeeds in conjuring up such dreadful horrors from the back recesses of his mind, I wonder about the rest of us. He has succeeded in weaving such a persuasive web of terror and suspense against a rather commonplace and familiar background that despite our desire to believe that such things cannot be, there remains a gnawing doubt, an uncomfortable tendency to feel a creeping fear. Perhaps he has discovered something that he wishes he never had — like Pandora.

It is very easy when you start reading The Manitou to assume that it is just another novel of mystery and suspense, but like burning phosphorus, once ignited, it sticks and envelops you, and refuses to stop until you have been consumed.

For true horror buffs The Manitou has a multi-pronged advantage. By combining elements like a master chef, the author has concocted something with a flavor that is vaguely familiar, enough to make you devour it voraciously, and afterward come to the realization that you have tasted something quite unique.

And now, to give you something to think about — here is a fact that may seem totally irrelevant, but that I recommend you stow away in your file of miscellaneous information. Like MSG it may enhance the flavor later. Fact: several years ago a fifteen-year-old Japanese boy developed what doctors thought was a tumor in his chest. The larger it grew, the more uncharacteristic it appeared. Eventually it proved to be a human fetus. This actually happened, whether Graham Masterton knew about it or not.

Whereas Rosemary's Baby gave us the minatory spawn of woman and Satan, and The Exorcist was a titanic clash between the forces of good and evil, The Manitou presents us with elements of both — plus the added ingredient of an intelligent menace that equally renders helpless the powers of the cross and modern science. It takes the familiar concepts of horror and manipulates the reader with a totally shocking and unique combination of terror woven into a solid suspense yarn.

— Bernhardt J. Hurwood

Graham Masterton

THE MANITOU

"On being ask'd what ye Daemon look'd like, the antient Wonder-Worker Misquamacus covered his face so that onlie ye Eyes look'd out, and then gave a very curious and Circumstantiall Relation, saying it was sometimes small and solid, like a Great Toad ye Bigness of many Ground-Hogs, but sometimes big and cloudy, with no Shape, though with a face which had Serpents grown from it."

H. P. Lovecraft

The phone bleeped. Without looking up, Dr. Hughes sent his hand across his desk in search of it. The hand scrabbled through sheaves of paper, bottles of ink, week-old newspapers and crumpled sandwich packets. It found the telephone, and picked it up.

Dr. Hughes put it to his ear. He looked peaky-faced and irritated, like a squirrel trying to store away its nuts.

" Hughes? This is McEvoy ."

"Well? I'm sorry Dr. McEvoy, I'm very busy."

" I didn't meant to interrupt you in your work, Dr. Hughes. But I have a patient down here whose condition should interest you ."

Dr. Hughes sniffed and took off his rimless glasses.

"What kind of condition?" he asked. "Listen, Dr. McEvoy, it's very considerate of you to call me, but I have paperwork as high as a mountain up here, and I really can't —"

McEvoy wasn't put. off. " Well, I really think you'll be interested, Dr. Hughes. You're interested in tumors, aren't you? Well, we've got a tumor down here to end all tumors. "

"What's so terrific about it?"

" It's sited on the back of the neck. The patient is a female Caucasian, twenty-three years old. No previous record of tumorous growth, either benign or malignant. "

"And?"

" It's moving, " said Dr. McEvoy. "The tumor is actually moving, like there's something under the skin that's alive. "

Dr. Hughes was doodling flowers with his ballpen. He frowned for a moment, then said: "X-ray?"

" Results in twenty minutes ."

"Palpitation?"

" Feels like any other tumor. Except that it squirms. "

"Have you tried lancing it? Could be just an infection."

" I'll wait and see the X-ray first of all. "

Dr. Hughes sucked thoughtfully at the end of his pen. His mind flicking back over all the pages of all the medical books he had ever absorbed, seeking a parallel case, or a precedent, or even something remotely connected to the idea of a moving tumor. Maybe he was tired, but somehow he couldn't seem to slot the idea in anywhere.

" Dr. Hughes? "

"Yeah, I'm still here. Listen, what time do you have?"

" Ten after three. "

"Okay, Dr. McEvoy. I'll come down."

He laid down the telephone and sat back in his chair and rubbed his eyes. It was St. Valentine's Day, and outside in the streets of New York City the temperature had dropped to fourteen degrees and there was six inches of snow on the ground. The sky was metallic and overcast, and the traffic crept about on muffled wheels. From the eighteenth story of the Sisters of Jerusalem Hospital, the city had a weird and luminous quality that he'd never seen before. It was like being on the moon, thought Dr. Hughes. Or the end of the world. Or the Ice Age.

There was trouble with the heating system, and he had left his overcoat on. He sat there under the puddle of light from his desk-lamp, an exhausted young man of thirty-three, with a nose as sharp and pointy as a scalpel, and a scruffy shock of dark brown hair. He looked more like a teenage auto mechanic than a national expert on malignant tumors.

His office door swung open and a plump, white-haired lady with upswept red spectacles came in, bearing a sheaf of paper and a cup of coffee.

"Just a little more paperwork, Dr. Hughes. And I thought you'd like something to warm you up."

"Thank you, Mary." He opened the new file that she had brought him, and sniffed more persistently. "Jesus, have you seen this stuff? I'm supposed to be a consultant, not a filing clerk. Listen, take this back and dump it on Dr. Ridgeway. He likes paper. He likes it better than flesh and blood."

Читать дальше