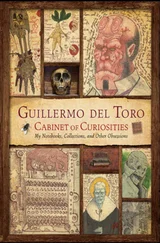

Джефф Вандермеер - The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джефф Вандермеер - The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I remember one last thing about Sir Locust. I almost left this out. It’s an alternative-origin story, which hinges on the third-century Syrian mystic, Saint Simeon Stylites.

Saint Simeon, as everyone knows, mortified his flesh by living for thirty-seven years at the top of a pillar. They say he subsisted on honey-dipped locusts, provided, I suppose, by respectful local peasants. I always wondered how the locusts got to the top of the pillar. Perhaps he had a bucket on a rope. I don’t see why not. Simeon was so holy, they say, that even the fleas and horseflies refrained from biting him.

But one day, a great grey locust lighted on his sun-blistered nose, as bold as you please. This locust called out to Simeon. “Now I shall bite you, old hermit,” it told him, “for excellent reasons. I can ignore your incessant consumption of my brethren bugs, soaked in the baby food of my cousin bugs, for such is the way of nature. But why should I excuse you from reciprocation? You may very well be considered a candidate for sainthood amongst the benighted Christians. But I, I’ll have you know, am a good Mussulman locust.” Whereupon the locust bit Simeon’s nose, drank his blood, and flew away.

The saint might have been excused for cursing the locust. Being a saint, he did the opposite. He prayed for the proud heathen insect, and God was so impressed that He followed the saint’s suggestions and blessed the locust with three boons. First, it grew as large as a horse—a miracle! Then it grew a human face on its head—an egregious miracle! The third boon, longevity, would only become apparent as the years went on. Saint Simeon had assumed that the locust would be grateful for its transformation. He hoped that it would convert to the true faith and save its tiny soul. (Saint Simeon didn’t get out much.) The locust remained an unrepentant Muslim, and to compound its ingratitude, it outlived the saint by decades.

In fact, it lived in Syria for eight centuries, doing whatever it did without making any impression on the historical record. Then came 1144, the fall of Edessa, and the Second Crusade. The ancient creaking locust purchased a sword, commissioned a fine suit of armor, and joined the army of defense. It marched into legend as an illustrious soldier of Islam and died, in due course, a soldier’s death.

The Christians, far from home, heard the story of the pious old locust from their wretched prisoners of war. And one Frenchman liked the story so well he stole it.

A Key to the Castleblakeney Key

Researched and Documented by Caitlín R. Kiernan

Excerpt from a postcard found among the correspondence of the late Dr. Thackery T. Lambshead, from Ms. Margaret H. Jacobs (7 Exegesis Street, Cincinnati, Ohio) to Lambshead; undated but postmarked January 16, 1979:

. . . kind of you to give me access to the collection. Such marvels, assembled all in one place! It was like my first visit to the Mütter, so crammed with revelation. But the hand, the hand—well, I’ll have to write you at length about the hand. I had a dream . . .

Excerpt from Archaeological Marvels of the Irish Midlands by Hortense Elaine Evangelistica (2009; Dublin, Mercier Press):

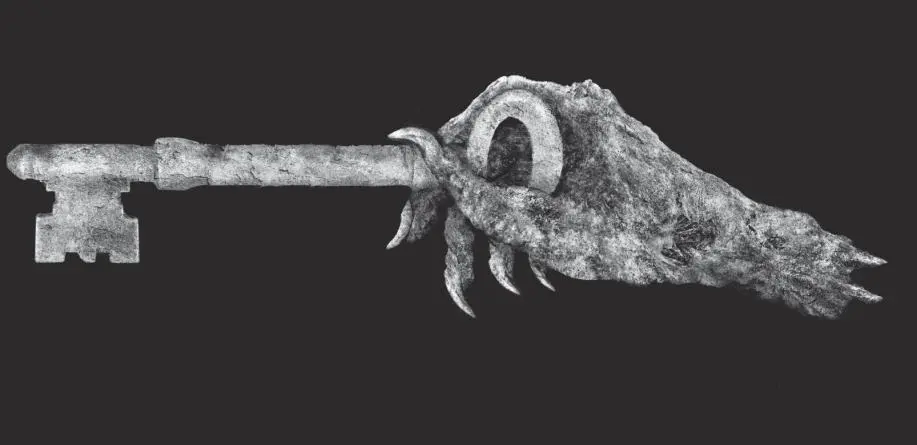

. . . and is undoubtedly one of the more curious and, indeed, grisly side notes to the discovery of the “Gallagh Man” bog mummy. The hand clutching the key is severed just behind the wrist, bisecting the radius and ulna bones (short sections of which protrude from the desiccated flesh). The bronze skeleton key is held firmly between the thumb and forefinger in such a way as to give one the impression that the hand was lobbed off only moments before the key would have been inserted into the lock for which it must have been fashioned. The key measures just under seven centimeters, from the tip end of the shank all the way back across the diameter of the bow, and the bit has three prongs. As mentioned earlier, the hand clutching the key is exceptionally small, measuring not much more than nine centimeters, diminutive even for a small child.

Littleway (2006) suggested the hand was not human at all, but, in fact, belonged to a species of Old World monkey ( Cercopithecidae ), probably a baboon or mangabey. This suggestion was subsequently rejected by Davenport (2007), who noted that no species of Old World monkey possesses claws, and even those few primitive New World species that do ( Callitrichidae , the marmosets, and tamarins) lack opposable thumbs. Certainly, the sharply recurved claws at the end of each finger remind one more of the claws of a cat or bird of prey than anything even remotely human. After his thorough examination of the hand, Davenport (ibid) concluded it to be a hoax, a taxidermied chimera fashioned from the right hand of a primate and the talons of a barn owl, then treated with various acids, salts, and dyes so as to give it the appearance of having been excavated from the peat deposits at Castleblakeney. Prout (2007) agreed with Davenport that the hand wasn’t that of a primate, but insisted it belonged to a three-toed sloth (despite the presence of five digits). Regardless, Davenport’s hoax explanation appears to have run afoul of carbon-dating carried out at Brown University (Chambers and Burleson, 2009b), which indicated the hand likely dates from between 300–400 B.C.E., which would make it much older than “Gallagh Man.” Also, a biochemical analysis of tissue samples taken from the hand reveal that it differs in no significant way from bog mummies known from Ireland and other locations across Northern Europe.

However, even if we accept that the strange hand from the late Dr. Lambshead’s cabinet is almost twenty-five hundred years old, we’re left with still another conundrum: the oldest known metal skeleton key (or passkey) dates back no farther than 900 C.E. Also, as Davenport was quick to point out, the only indication that the hand was recovered from the vicinity of Castleblakeney is a charred and faded label apparently written in Thackery Lambshead’s hand.

As it stands, the matter may likely never be resolved to anyone’s satisfaction. Following a break-in on the evening of April 12, 2010, the hand and key were discovered to be missing from the collection of Brown University’s Department of Anthropology, where the artifact was on long-term loan from the National Museum of Ireland ( Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann ). Reports indicate that the thieves took nothing else. . . .

Aeron Alfrey’s eerie rendering of the Castleblakeney Key

Excerpt from “An Act of Rogue Taxidermy? Preliminary Report on the Morphology and Osteology of the ‘Castleblakeney Hand,’ ” P. O. Davenport, American Journal of Zooarchaeology, vol. 112, no. 1 (2007):

. . . that evidence provided by these high-resolution X-ray CT images leads the author to the conclusion that the artifact is no more representative of the remains of a single animal than are other chimeric forgeries, including jackalopes, Barnum’s “Feejee mermaids,” the Minnesota iceman, the Bavarian Wolpertinger, Rudolf Granberg’s skvader, or the fur-bearing trout of Canada and the American West. As will be demonstrated, these X-rays reveal fully intact terminal ungual phalanxes (bones and keratin sheaths) indistinguishable from those of members of the family Tytonidae (barn owls), articulated to the proximal metacarpophalangeal and ginglymoid surfaces of the phalanges of an adult Barbary macaque ( Macaca sylvanus ). It is not possible, at this time, to determine whether or not Lambshead himself was involved in fashioning the hand or whether he believed it to be authentic, having been duped by its creator, but that question is irrelevant to the current investigation.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.